What is congressional dysfunction?

Congress, in this case, refers to the legislative branch of the United States government. It's composed of the House of Representatives and the Senate. And it is, by far, the most powerful branch of the US government.

Congress is mentioned first in the Constitution, and its enumerated powers far exceed those of the Supreme Court or the presidency. The simplest way to see this is to envision a direct collision between Congress and the other branches: Congress can pass legislation into law over the president’s veto. The president, meanwhile, doesn’t even have a way to make Congress consider legislation, much less pass anything into law over congressional objections. Meanwhile, nominees to the Supreme Court must pass a vote in the Senate, and Congress retains the power to alter the composition of the Court (the Court has nine members currently because Congress decreed it would have nine members in the Judiciary Act of 1869).

When people talk about congressional dysfunction they usually mean that Congress, despite its vast authority, seems paralyzed in the face of the nation's toughest problems. The paralysis usually stems from disagreements between the two parties, and is exacerbated by the unusual construction of the US Congress, which makes it possible for one party to control the House while the other controls (or at least exercises veto power) in the Senate. A secondary (and arguably related) problem people are sometimes referring to is the perception that the personal relationships between members of the two parties are angrier than they've been in the past.

Is Congress popular?

A key question in assessing whether Congress is somehow broken is whether the American people approve of the job it's doing. After all, the point of Congress isn't passing laws. It's representing the will of the people. If they're happy with the job Congress is doing then it's hard to argue that the institution has collapsed into dysfunction.

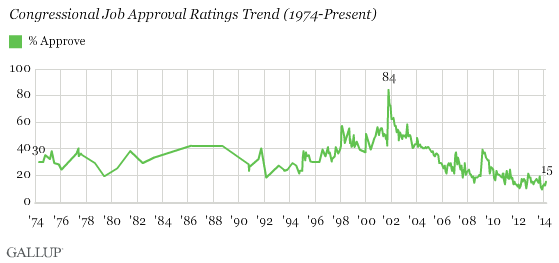

But according to multiple pollsters, Congress has never been less popular than in recent years. Gallup's data, for instance, shows public approval of Congress is lower than at any time since the venerable polling firm began asking the question:

In recent years, Congress's approval ratings have routinely fallen into the single digits. Senator Michael Bennet, a Democrat from Colorado, notes that this means Congress is less popular than the Internal Revenue Service, Richard Nixon during Watergate, banks, lawyers, Paris Hilton, and communism:

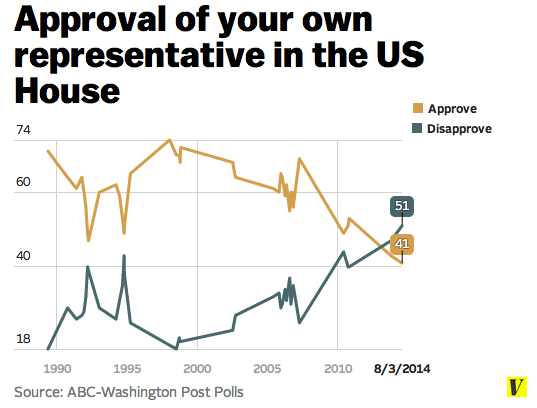

There's typically a catch to these numbers: though Congress as an institution is incredibly unpopular (another poll found them to be less popular than lice, traffic jams, and Nickelback), individual members of Congress are typically well-liked by their constituents. In the 2012 election, for instance, 90 percent of congressional incumbents who sought new terms were reelected. To put it simply, people hate Congress but they tend to like their member of Congress. But that's changing. A July 2014 Washington Post/ABC News poll found, for the first time, that a majority of Americans disapproved of their own member of Congress:

But a deep truth in all these polls is that while Americans are angry that Congress can't seem to get anything done, they often disagree on what should be done. Conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats both disapprove of the job Congress is doing but for very different reasons.

Is Congress less productive than it used to be?

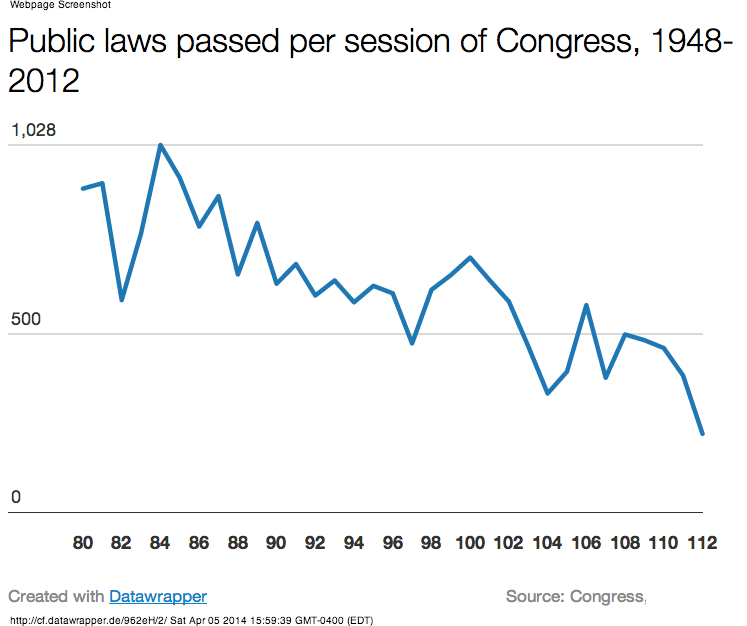

Congressional productivity is a tricky thing to measure. The simple approach is to count the number of public laws passed by different congresses. Give that a shot and you'll see that yes, recent congresses have been some of the least productive since 1948, when we began keeping track of these numbers:

The numbers show the 112th Congress was the least productive in history, passing about 220 public laws (many of which are minor laws, like bills to name courthouses). The current Congress — the 113th — is not on that graph because it doesn't end till January of 2015. But so far, it's on track to be even less productive than the 112th.

Simply tallying up public laws has some problems, though. It doesn't account for the scope and importance of the laws passed. Imagine a Congress that passed nothing but Obamacare and another Congress that passed nothing but a law naming a courthouse in Texas after George H.W. Bush. This measure would count those two congresses as equally productive, though that's plainly absurd.

It also makes no allowance for Congress's tendency to pack more and more policy into a single bill. "The measure takes no account — it cannot — of Congress's creeping tendency over the decades to bundle a lot of items into single big bills," wrote congressional scholar David Mayhew in Politico. But that trend makes it seem like modern congresses are much less productive than congresses from, say, the 50s, even though we know that much of the difference is simply how much gets stuffed into individual bills.

Mayhew advises that we need to "use our heads and consult the history" to develop a more informed measure. Productivity, he writes, should be measured by "laws that alter existent government policy to a significant degree." By that measure, it's clear that the 112th and 113th congresses have achieved relatively little. The 111th Congress, however, passed a slew of policy-altering laws ranging from Obamacare to Dodd-Frank to the stimulus. By any measure, it was astoundingly productive, showing that when one party holds sufficient power over congress, much can still get done.

Of course, measuring the number of major laws passed says little about whether those laws were any good. House Speaker John Boehner made a variant of this point when he told CBS, "We should not be judged on how many new laws we create. We ought to be judged on how many laws we repeal." Of course, repealing a law also requires passing a law to enact the repeal, and that's not happened much in recent years, either.

So whether you're looking for big new policies to address the country's problems or the repeal of significant laws that you think are creating the country's problem, congressional productivity has deteriorated markedly since 2010. But if you like the country's legislative status quo, then the last few years have been great!

What is political polarization?

Political polarization simply measures overlap between the two parties. A high level of political polarization means that Republicans agree with Republicans and that Democrats agree with Democrats.

There was a time, not so long ago, when this wasn't true — when many elected Republicans agreed more with the Democrats than with other Republicans, and vice versa — and leading political scientists thought it a great crisis for our democracy. In 1950, the American Political Science Association's Committee on Political Parties released a report calling on the two parties to sharpen their disagreements so that the American people had a clearer choice when casting their ballots.

The political scientists eventually got their wish. According to the polarization measures kept by political scientists Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal, party polarization is higher in today's Congress than at any time since the late 1800s:

Political polarization is sometimes used as a synonym for political extremism, which it is not. It is sometimes used as a stand-in for political incivility, which it also is not. The 1960s and 1970s were a time of incredible political controversy and tumult. But political polarization was at a low ebb, because though Vietnam and the civil rights movement and the Great Society split the country, they did not cleanly split the two political parties. The Civil Rights Act of 1965 is a good example: The law was primarily pushed by politicians in the Democratic Party, but many northern Republicans supported it while southern Democrats were its fiercest opponents.

A close examination of this period also shows why consensus should not be viewed as an unalloyed good. The de-polarized political system if the 40s and 50s relied on a bipartisan consensus in favor of segregation. Extremely conservative Southern Democrats remained in the Democratic Party so long as the Democratic Party kept protecting the architecture of southern racism. As soon as that ended, conservative Southern Democrats like Strom Thurmond migrated to the Republican Party, and the system began to polarize.

The problem with party polarization is that the American political system typically requires bipartisan coalitions in order to get big things done, but during periods of intense political polarization, it is almost impossible for those coalitions to form.

Have both parties polarized equally?

No. Virtually every measure of political polarization shows that Republicans have moved much further right than Democrats have moved left. "Despite the widespread belief that both parties have moved to the extremes, the movement of the Republican Party to the right accounts for most of the divergence between the two parties," writes political scientist Nolan McCarty. "Since the 1970s, each new cohort of Republican legislators has taken conservative positions on legislation than the cohorts before them. That is not true of Democratic legislators."

Or, as congressional scholars Thomas Mann and Norm Ornstein put it, "while the Democrats may have moved from their 40-yard line to their 25, the Republicans have gone from their 40 to somewhere behind their goal post."

Scholars call this "asymmetric polarization." Mann and Ornstein argue that it is the central cause of today's dysfunction. "When one party moves this far from the mainstream, it makes it nearly impossible for the political system to deal constructively with the country's challenges," they write.

What is the filibuster?

The filibuster — or, to be technical, Senate Rule XXII — permits a senator or group of senators to stall the chamber's business until stopped by 60 of their colleagues.

A common misconception is that the stalling tactic has to be a lengthy speech. That's good for movies, but it's not actually how the Senate works. Most filibusters use procedural delays, like asking the Senate to repeatedly check who is present. And many filibusters are so-called silent filibusters: they're privately communicated to the office of the Senate Majority leader, and if the Majority Leader decides he can't break the filibuster and doesn't want to waste time on it, the bill simply isn't brought to the floor.

The filibuster doesn't appear in the Constitution and scholars aren't precisely sure how it was created. The reigning theory is that it dates back to a rules overhaul pushed by Vice President Aaron Burr. He encouraged the Senate to delete the motion to return to the previous question (the House retains this rule, and it's what stops filibuster there). Only later did anyone realize the Senate had just deleted the only rule that permitted it to shut off debate.

Even so, filibusters were exceedingly rare for most of the Senate's history. It wasn't until 1917 that the Senate felt the need to adopt a rule letting a supermajority of two-thirds end the filibuster. It wasn't until 1975 that the Senate lowered that threshold to today's three-fifths supermajority. But in recent years filibuster use has skyrocketed. There were more filibusters — as measured by votes to end a filibuster — between 2009 and 2010 than there were in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s combined.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3516878/filibuster_cloture_votes.0.png)

The rise of routine filibusters is related to the rise of party polarization: the tactic, which was once used primarily by individual senators or small groups of senators on issues they were particularly passionate about, has become a tool that the minority party uses to routinely stymie the majority party. That wasn't possible when many in the minority party agreed with the initiatives of the majority party. But it's possible now that they don't.

The rise of the filibuster has utterly change the way the US Senate conducts business. What was once an institution where a majority ruled has become an institution where only a supermajority can enact its agenda. "Over the last 50 years, we have added a new veto point in American politics," said Gregory Koger, a University of Miami political scientist who researches the filibuster. "It used to be the House, the Senate and the president, and now it's the House, the president, the Senate majority and the Senate minority. Now you need to get past four veto points to pass legislation. That's a huge change of constitutional priorities. But it's been done, almost unintentionally, through procedural strategies of party leaders."

Though Rule XXII says that the filibuster can only be changed by a two-thirds majority of the Senate, the Constitution's promise that each Senate can decide its own rules renders that moot. In 2014, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid led Democrats in a successful bid to make executive-branch nominations and non-Supreme Court judicial nominations immune from the filibuster. It passed 52-48.

Is money the problem?

Maybe part of it? but definitely not all of it.

The word political scientist Nolan McCarty uses for the relationship between money and polarization is "complex." He's written that "while there is little evidence that the origins of greater polarization lie in campaign finance, the growing participation of ideologically oriented donors appears to have exacerbated the problem."

To understand what he means, it's worth looking at the Sunlight Foundation's data on the the .0001 percent — or 31,385 individuals — who donated more than a quarter of the $6 billion in identifiable contributions during the 2012 campaign. This money, the Sunlight Foundation notes, was highly polarized. About 85 percent of these donors gave more than 90 percent of their money to one party or the other:

How important was this money? It's hard to say. But it was pervasive. The Sunlight Foundation notes that "not a single member of the House or Senate elected last year won without financial assistance from this group," and, perhaps more strikingly, "84 percent of those elected in 2012 took more money from these 1 percent of the 1 percent donors than they did from all of their small donors (individuals who gave $200 or less) combined."

Political scientist Lee Drutman crosschecked dependence on these top donors against polarization. "The more Republicans depend on 1 percent of the 1 percent donors, the more conservative they tend to be," he concluded. "There is no observable relationship among Democrats." That suggests that money from conservative megadonors is supporting more political polarization than money from liberal megadonors.

But it's not just megadonors. Small donors are polarized too. Political scientist Adam Bonica has studied which candidates are most effective when they ask supporters for money. "The most successful small-money fund-raisers mix media exposure with partisan taunting and ideological appeals," he's concluded. Rep. Michelle Bachmann, for instance, raised more during the 2010 campaign cycle than all 48 members of the moderate Blue Dog Caucus combined.

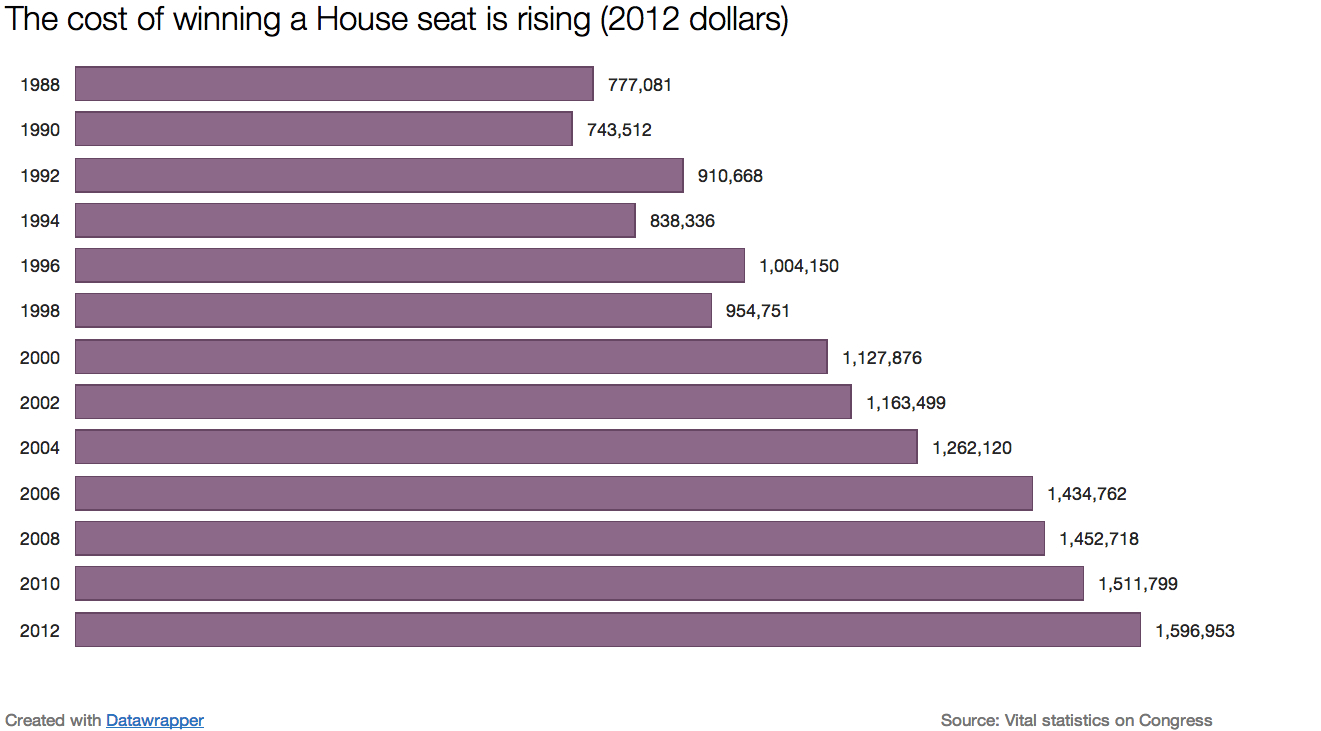

And this is all happening at the same time as the cost of winning a congressional seat is rising sharply:

Not all money is polarizing, of course. Many corporations donate money for much more transactional reasons. They want to see something get done, or in some cases, get undone. They don't want Congress gridlocked. They want it working — for them. But the rise of highly ideological money is clearly winning. An example came when the AFL-CIO and the Chamber of Commerce — historically two of the strongest lobbies on Capitol Hill — both endorsed an effort to boost infrastructure spending in 2011. The bill went nowhere.

Didn't the Founding Fathers want Congress to be gridlocked?

The Founding Fathers created a system in which different branches of the government would serve to check each other. But they expected the primary competition in the government to be between those branches. They didn't believe the US political system would, or should, have political parties (though shortly after founding the system they went on to start a bunch of them). Today's system, in which the primary competition comes from organized political parties struggling across different branches of government, is quite far from the system they envisioned.

In certain cases, the Founding Fathers did consider rules that would lead to more gridlock. For instance, there were proposals to require supermajorities for congressional action. But they ultimately rejected those ideas. In Federalist 58, James Madison explained: "In all cases where justice or the general good might require new laws to be passed, or active measures to be pursued, the fundamental principle of free government would be reversed. It would be no longer the majority that would rule; the power would be transferred to the minority."

That said, the Founding Fathers have been dead for some time, and even when they were alive they disagreed about quite a lot. Anyone who confidently claims they know how the Founding Fathers would feel about today's political problems is a liar. It's likely that Alexander Hamilton would have some questions about airplanes and African-American presidents before he'd render an opinion on congressional productivity.

Why won't Obama lead?

The president has little formal power to make Congress do anything. Unlike in parliamentary systems, the president is not the leader of the party that wields power in the legislature. Instead, the president often leads the party that is the minority in one or both chambers of Congress. And in those cases the president's intervention can actually make Congress less cooperative.

Elections are zero-sum affairs: for one party to win the other party has to lose. Since elections are typically a referendum on the party in power that sets up a very simple incentive for the minority party: they need the majority party to fail, or at least to be seen to fail, if they're to regain power. What makes the American political system unusual is that its checks and balances, alongside unusual minority protections like the filibuster, actually give the minority party the power to make the majority party fail. A system that typically requires the minority party's cooperation to work is nevertheless built to penalize that cooperation.

The result is much as you'd expect. When the president takes a position on an issue the opposing party becomes far more likely to take the opposite position. In a clever study, political scientists Frances Lee proved this by looking at noncontroversial issues, like whether NASA should try and send a man to Mars. She built a database of eighty-six hundred Senate votes between 1981 and 2004. Typically, these votes fell along party lines just a third of the time. But but when the President took a clear position the likelihood of a party-line vote rose to more than half.

"Whatever people think about raw policy issues, they're aware that Presidential successes will help the President's party and hurt the opposing party," Lee explained. "It's not to say they're entirely cynical, but the fact that success is useful to the President's party is going to have an effect on how members respond."

The incentives for conflict — and the absence of tools for resolving that conflict —between the executive and the legislature creates a deep tendency towards instability. Internationally, America's political structure is rare for precisely this reason. As the late sociologist Juan Linz wrote in 1989, in systems like the US, "no democratic principle exists to resolve disputes between the executive and the legislature about which of the two actually represents the will of the people." So how has America's system survived for so long? Linz attributed it to "the uniquely diffuse character of American political parties."

Well, the once-uniquely diffuse nature, anyway.

Could a third party fix Congress?

Probably not.

Political scientist Ronald Rapaport wrote the book on third parties. Literally. It's called Three's a Crowd, because of course it is. And the key thing he found about third parties is that "they need some sort of unique agenda. There has to be a reason why you're going to support a third party."

That is to say, third parties are a political weapon: they force the system to confront issues it might otherwise prefer to ignore. Take Ross Perot, the most successful leader of a third party in recent American history. "People like to think of Perot as being centrist. But he was not," says Rapoport. "He was extreme on the issues he cared about. And with Perot, it was economic nationalism and balancing the budget."

Eventually, those third parties get co-opted. Bill Clinton was much more intent on reducing the deficit because Perot showed the issue's power. Newt Gingrich's Contract With America echoed Perot's United We Stand. By 1996 there wasn't much left for Perot and his party to do.

But that's what third parties are good at: they mobilize popular opinion to force issues to the front of American politics. What they're not good at is actually working within the political system.

A third party presidency

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2528976/92484471.0.jpg)

Ross Perot can hear you now. (PETER MUHLY/AFP/Getty Images)

Let's start with the likeliest scenario: a third-party president.

Right now, the basic problem in American politics is that one of the two major political parties has an interest in destroying the president. As incoming Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell said in 2010, "the single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president."

The statement is often used to paint McConnell as uniquely Machiavellian, but in truth, it's banal: the single most important thing any minority political party wants to achieve is becoming the majority party. That's not because they're evil; it's because they believe being in the majority is the best way for them to do good. But the way for them to get there is to destroy the incumbent. Hence, the gridlock we see today.

A third-party president would change this in one big way: now both major political parties would have a direct incentive to destroy the president.

"The reason congressional parties work with the president from their party is that they share policy goals and because they share electoral goals," says Sarah Binder, a congressional scholar at the Brookings Institution. "You put a Michael Bloomberg at the top and maybe they still share policy goals but they don't share electoral goals. So you sever that electoral incentive."

A third party in Congress

Arguably, a third party could attack congressional gridlock at its source: by winning seats in Congress and then doing ... something ... to fix the chamber. But that something is hard to imagine.

I asked Binder for the rosiest possible scenario for a congressional third party. But she couldn't come up with much. "I can't even quite wrap my head around the politics, the electoral politics, the institutional politics, that would ever lead a third party to be in a position to make a difference in Congress," she said. "Everything in Congress is structured by the parties. If you want committee assignments, it's the parties that control committee assignments. Unless you can displace a major party I don't see how you get the toehold that gives you institutional power."

Rapoport didn't have much more of an answer. Third parties, he said, "are bad at process." They tend to be structured around a charismatic founder or a particular issue but, if they get far enough to actually wield power, they're ground to death by the byzantine institutions of American politics.

You can see that in Congress now, in fact. There are a number of third-party candidates serving in the Senate. Maine's Angus King, Vermont's Bernie Sanders, and Alaska's Lisa Murkowski were all elected as third-party candidates (Murkowski ran as a Republican write-in after losing the Republican primary). But in order to wield any power they've allied themselves with one of the two major parties. Sanders and King caucus with the Democratic Party and vote like typical Democrats — indeed, Sanders is thinking about running for president as a Democrat. Murkowski caucuses with the Republican Party and votes like a Republican. Even when Congress has three parties, it really only has two.

If a third party did win seats in Congress and accepted less institutional power for more party coherence, it's hard to say what problems it would solve. Congress is riven by disagreement and an inability to compromise. A third party would simply add another set of disagreements and another group who could potentially block action to the mix.

You didn't answer my question!

Oh no! This is very much a work in progress. It will continue to be updated as events unfold, new research gets published, and fresh questions emerge. So if you have additional questions or comments or quibbles or complaints, send a note to ezra@vox.com.

How have these cards changed?

This is a running list of substantive updates, corrections, and additions to this card stack. These cards were last updated on January 2, 2015. Here is a summary of edits:

- The chart on card 4 was swapped in favor of a new VoteView chart containing data from the most recent congress.

- New polling on congressional popularity was added.

- The card "Could a third party fix Congress" was added.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62289977/107982293.0.1539286133.0.jpg)