/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/34790503/450380792.0.jpg)

Since 2010, there's been a lot of hype about the Tea Party's power to threaten Republican incumbents in primary elections. But now that Thad Cochran has held on to win his primary, there are still only 2 members of Congress who've lost renomination this year — Majority Leader Eric Cantor, and 91-year old Ralph Hall of Texas.

So is the primary threat overhyped? I spoke to Professor Robert Boatright of Clark University, a leading expert on Congressional primaries. His book Getting Primaried is the most comprehensive recent analysis of the topic. We spoke before the outcome of Cochran's race was known, and he gave his take on what's been happening. Here's our interview, edited and condensed for clarity:

Andrew Prokop: What does the media get wrong about primaries?

Robert Boatright: Primaries are exciting. They're like a Sopranos episode when you find out somebody in your gang is consorting with the other side, they get knocked off — the drama's irresistible. "Ooh, the right wing got that guy, because he was too liberal." So it's not a surprise that people tend to find good stories here.

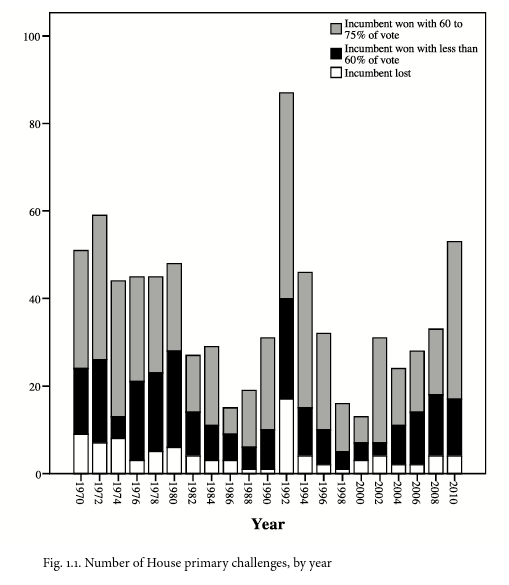

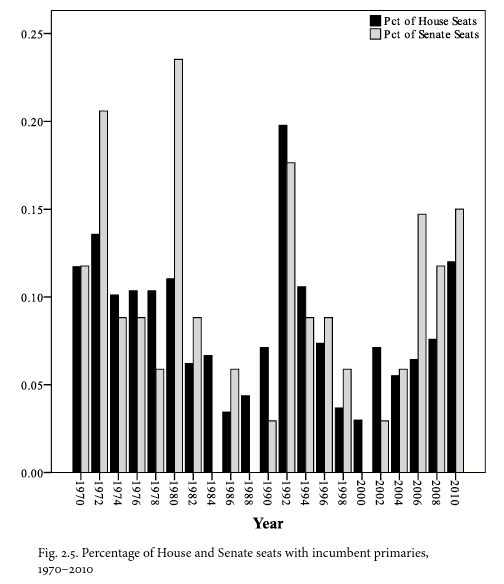

The error that's been made over the last few years is that there really haven't been too many more stories like that recently. There aren't very many primary challenges that manage to catch on, so it's hard to generalize. But the numbers we do have suggest that the overall number of challenges has stayed similar over the past few decades. So far, this year has been pretty typical. Two incumbents losing primaries is pretty standard for the past decade.

Robert Boatright, "Getting Primaried"

AP: Are there policy consequences of this media hype?

RB: I think it has been taken as a fact that primaries are more competitive now — even though it's not really a fact, the perception is out there. And this hype sort of scares mainstream Republicans to death. A smart member of Congress is always paying attention to what's going on in the district, and probably everybody in Congress is a little bit paranoid about that. But I think the paranoia used to be manifested in spending a lot of time getting to know your constituents. Now the paranoia is manifested in, for instance, making sure you’re not seen on the same stage as President Obama, or that you don’t give a challenger any ammunition to allege you’re a centrist.

Robert Boatright, "Getting Primaried"

AP: How do outside groups try to strategically use primaries?

RB: Primaries are low-turnout elections, and the media basically goes bonkers every time an incumbent loses one. So they're low-cost opportunities for groups like the Club for Growth or the Tea Party to get a lot of attention and scare incumbents.

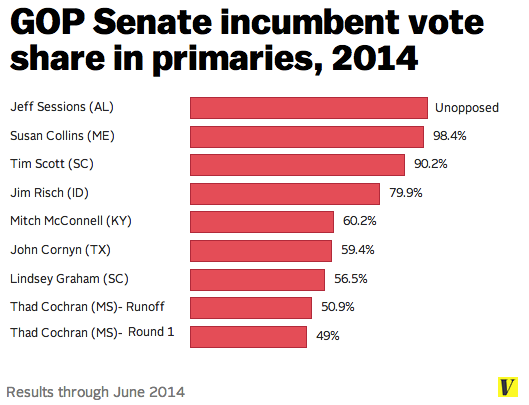

They can only do that, though, if they focus their money very carefully. The Club doesn't have the money to go around threatening a lot of incumbents. But if they figure out two or three people to go after, they have a high probability of either winning one race or making it so close that it winds up being a story in itself. This year has been pretty typical in that regard, especially with the Mississippi Senate race. Conservative groups kind of looked around, asking, are we gonna go after Mitch McConnell, Pat Roberts, Lindsey Graham? McDaniel was the guy they settled on. He got the money and the attention.

In the House, the challenger who seems to have gotten the most money was Brian Smith, who challenged Representative Mike Simpson of Idaho. There was a concerted effort of outside money there, but it didn't work out — Simpson won. In contrast, the Cantor thing was a surprise to the groups. There was no money invested in Cantor's opponent.

AP: In your book, to track the number of primary challenges over time, you look at any race where the incumbent is held to below 75 percent of the vote. So far this year, 4 of 8 GOP senators have gotten below that margin in primaries — even though they all won. Might that indicate that primaries are becoming more regular for Republican senators?

RB: We'll see how that develops in the next few years. The problem with studying the Senate is that there's so many fewer races, while a lot of the House variation washes out over time. I think it makes a bit of sense. But we're about halfway through the primary season, so it could also be a function about which races we happen to have seen so far.

For my book, I used 75 percent even though it's a generous measure of competitiveness. You can't include every primary challenger because there's a lot of variations in ballot access laws by state. For instance, Maryland has very generous ballot access laws, so there's usually a lot of people running in primaries there. So I felt that cutoff captured a level at which the incumbent might notice a challenger.

Robert Boatright, "Getting Primaried"

AP: You also categorize primary challenges by topic — whether they were waged for ideological reasons, or because of the incumbent's age or perceived ineffectiveness, or scandal, or other reasons. And your book found a small increase in ideological challenges in recent years. Do you think this trend will continue?

RB: Every year you see maybe 30 or 40 cases where a somewhat competitive primary challenger that emerges. The question for that challenger is — if you want to win that seat what's the best argument you can make? You could say the incumbent's too old, or that he's a crook. But the depth of conservative animosity toward the Republican Party recently means these ideological arguments can be very effective.

One indicator of an ideological challenge can be how much money the challenger raises from outside the state. If they raise a lot, one would assume that they're getting help from somebody. There's no reason for anybody in Massachusetts to give money to a House primary challenger in Iowa. It's a sign that somebody's bundling, or it could be somebody in the national media like Glenn Beck, or some sort of coordinated effort to talk up a particular primary. Often, candidates who can really cut through the clutter and make strong liberal or conservative arguments develop a strong national following — and the Internet has made it easier for them to raise money from outside their states or districts.

But we've been through a really unusual period of high turnover, historically, over the last few years. We basically had three wave elections in a row and a redistricting year right after that — redistricting years tend to be weird in terms of the number of primaries. So I'm not convinced we're seeing a trend of increasing ideological primaries. We saw a period of high turnover, and that's a trend that's not likely to continue.