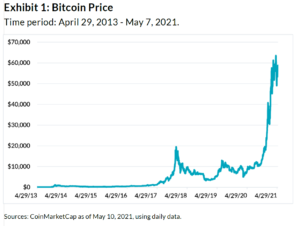

The chart below speaks volumes to the spectacular rise in cryptocurrency investing. Bitcoin has surged nearly 40,000%1 (that is not a typo) since April of 2013, for an annualized return of approximately 110%.2 It has not been a smooth ride—that return has come with an annualized volatility of 81%, but the risk-adjusted returns were still very attractive (Bitcoin’s annualized Sharpe ratio was ~1.3 over this period).

Bitcoin trading volumes have increased meaningfully during the pandemic. In January 2021, Cointelegraph reported that volume in the Bitcoin market doubled, smashing previous all-time records.3 In fact, Bitcoin’s five-day average daily trading volume as of April 18th was approximately $77B,4 roughly 70% of the NASDAQ’s five-day average volume.5

The incredible price appreciation (leading to bandwagon and “fear of missing out” effects), massive government stimulus, and people around the world spending more time at home and in front of screens have certainly contributed to Bitcoin’s meteoric rise, especially among retail investors. Increasingly, institutional investors are entering the crypto space, with managers like Skybridge,6 Blackrock,7 and Tudor8 announcing the addition of crypto to their investment universes or even the launch of crypto-dedicated funds. In fact, PWC estimates that crypto hedge fund assets increased 100% from $1 to $2 billion in 2019, and it seems like it’s only increasing from there.9

As institutional investors evaluate crypto assets, how can they think about properly assessing their risks, especially in the context of a broader, multi-asset class portfolio? In this Street View, we will seek to answer this question. We explore how traditional financial risk factor models can potentially explain the risk of the largest crypto asset, Bitcoin. We then seek to understand the extent to which there are influential, common risk drivers across crypto assets using a statistical technique called Principal Components Analysis.

Using Financial Risk Factors to Explain Risk in Crypto

Many established risk models, like our own Two Sigma Factor Lens, are constructed to explain the majority of risks and returns in traditional financial portfolios, which often include heavy allocations to well-established asset classes like stocks, bonds, commodities, and fiat currencies, as well as to well-known investment strategies such as trend following in macro asset classes and value investing in stocks.

To our knowledge, most financial risk models do not incorporate idiosyncratic crypto risk as a “factor.” If crypto has mostly unique risks and returns that are specific to the crypto market, then any portfolio with allocations to crypto will have residual, or unexplained risk, according to these factor risk models. In order to understand the extent to which crypto is correlated with factors in traditional financial markets, let’s start by analyzing Bitcoin’s relationships with the factors in the Two Sigma Factor Lens.10 Bitcoin is the largest crypto asset by market cap and is arguably the most canonical. For a brief overview of some of the ways that investors can transact in crypto and obtain other types of crypto exposures, please see Appendix 1 in the pdf version of this article.

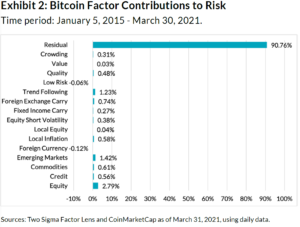

The exhibit below shows how the Two Sigma Factor Lens, which does not include a crypto factor, attempts to explain Bitcoin. 91% of Bitcoin’s risk since January 2015 was unexplained. This is a relatively high amount of residual risk. For context, broad-based equity indices like the S&P 500 exhibited <1% residual risk over this period. Individual stocks typically carry higher residual risk, but much lower than that of Bitcoin’s. For example, <50% of Apple’s risk was unexplained over this period.

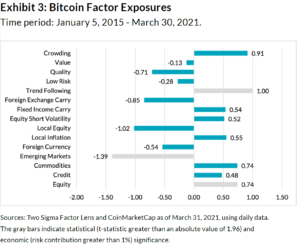

The 9% of Bitcoin’s risk that was explained by the model can be attributed primarily to three significant factor exposures: positive Equity, positive Trend Following, and negative Emerging Markets. There were other statistically insignificant factor exposures that are worth diving into as well, namely positive Commodities, positive Local Inflation, and negative Foreign Currency.

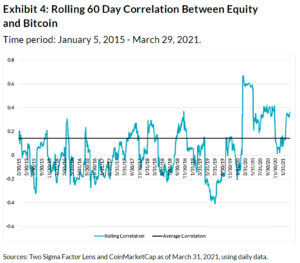

Before diving into the idiosyncratic component of crypto’s risk in the next section, let’s first analyze Bitcoin’s relationships with other risk factors. First: Bitcoin’s relationship with Equity. While Bitcoin’s beta to the global Equity factor was 0.74, the correlation was much lower at only 18% over this period. The higher beta was due to differences in volatilities (~15% annual volatility for Equity and ~73% for Bitcoin). We display the rolling 60 day correlation below and find that the correlation has been elevated for much of 2020 and 2021, peaking around 60% during the depths of the COVID market crisis last year, as we covered in a Venn blog post on “safe-haven” assets.

Bitcoin’s positive relationship with the Trend Following factor likely indicates that Bitcoin tends to perform well when macro markets are trending in one direction or another, and it tends to perform poorly when macro markets are choppy and directionless. Upon further analysis, we found that Bitcoin appeared to be most highly correlated with trend following in equity markets over this period.

We should also explore Bitcoin’s positive relationship with the Local Inflation factor, which is designed to measure exposure to an U.S. inflation hedge.11 Many investors have hypothesized that Bitcoin serves as protection against rising inflation given the fact that it is decentralized and isn’t at risk of being inflated by a government. In addition to the positive exposure observed in Exhibit 3, Bitcoin’s univariate beta to 10-year inflation breakevens (which serve as a measure for the market’s expectations for inflation) was 0.76 over the same period with a correlation of 15%. While this might not seem like a significant relationship at first glance, compare it to a commonly viewed “inflation hedge” like gold, which experienced a correlation to inflation breakevens of 9% over the same period. So in that sense the two assets (Bitcoin and gold) may be on par with regard to “inflation hedging.”

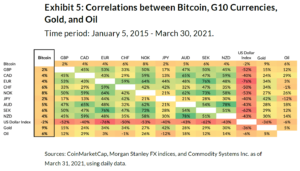

Speaking of gold, what is Bitcoin’s relationship with Commodities? We can see in Exhibit 3 that Bitcoin’s Commodities factor exposure was positive, but not significant. Bitcoin exhibited slightly positive correlations with gold and oil over this period, as displayed in Exhibit 5. Here we also observe gold’s strong negative relationship with the USD. Interestingly, Bitcoin didn’t seem to have a negative relationship with the USD — in fact, the cryptocurrency appeared to have no meaningful correlation with the dollar index.

Finally, what about Bitcoin’s relationship with fiat currencies? The lack of a significant relationship to the Foreign Currency factor in the Two Sigma Factor Lens is interesting and perhaps unexpected, given both the factor and Bitcoin (in this instance12) are expressed relative to the USD. In Exhibit 5 we show Bitcoin’s relationship with the USD and all other G10 currencies. The cryptocurrency doesn’t appear to have any meaningful correlation with any fiat currency.

To summarize, Bitcoin is not easily explained by the Two Sigma Factor Lens, nor is it substantially correlated to other currencies or any of the major commodities. This leaves us with the following question that we will spend the rest of this Street View analyzing: are there any common risk drivers among cryptocurrencies themselves, or are they each their own beast, carrying a unique, idiosyncratic return even relative to each other?

Correlations Among Crypto Assets

To examine common risk drivers across crypto, we first need to establish a universe of crypto assets. We selected the 10 coins,13 including Bitcoin, Ethereum, and Dogecoin, that had the highest 30-day trading volume as of April 19th, according to CoinMarketCap, and that had at least 3 years of price history.14

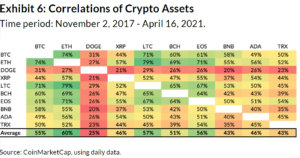

Below we show the correlation matrix of the returns of these crypto assets over the last few years. At first glance, there appears to be some common risk driver across these assets, as the average correlation was notably positive at 48%. In comparison, the average correlation across the fiat currencies (G10-ex USD) in Exhibit 5 that make up the Foreign Currency factor in the Two Sigma Factor Lens was 46%.

A few interesting observations from the correlations across crypto assets: first, there was not a single negative correlation in the entire matrix. All of the crypto assets exhibited positive correlations.

Second, the coin that appeared to be the most unique was DOGE with an average correlation of only 25%. DOGE is a largely speculative coin that has surged recently due to Reddit forums and endorsements from Tesla CEO, Elon Musk.15 The coin started out as a lighthearted joke based on an internet meme, and it has largely been abandoned by developers, however, that could change with the recent price surge and interest.16

Finally, there exists a notably high correlation between the two largest coins by market capitalization: BTC and ETH.17 Their correlation over this period was 74%. This is particularly interesting because of the different use cases of these two assets. While BTC’s original intended use case was to serve as a decentralized medium of exchange, its primary function today is to serve as a store of value. ETH has that use case as well, but it expands on that by representing a platform on which to build applications using its cryptocurrency, ether. Some investors that are considering entering the crypto space might initially “get their feet wet” with BTC given its relatively long price history and market size. And while ETH still offers a decently large market, it is a slightly more complex entry into crypto, as it can be considered not only as a “store of value” like BTC, but might also serve as a proxy for DeFi (or decentralized finance) exposure.17

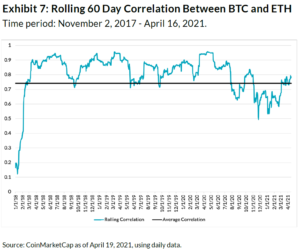

Below we see how the correlation between these two coins has changed through time. While the correlation has always been in positive territory, the correlation between the two was much lower a few years ago. It substantially picked up around the Q1 2018 crypto crash when both coins suffered their worst quarterly losses up to that point as regulatory scrutiny on crypto was picking up and tech giants, like Facebook and Google, banned cryptocurrency advertising.19

The correlation has remained high since then, reaching a recent peak in the first half of last year, again when there was a crypto crash. BTC and ETH were both down ~40% on March 12, 2020 when a massive risk-off move across financial markets severely impacted the heavily leveraged crypto markets (as we covered in a previously-mentioned Venn blog post on “safe-haven” assets). The correlation has declined a bit since then, but has been picking up again more recently.

In summary, we see fairly high correlations among the ten coins in our universe. Even BTC and ETH, which are two seemingly very different assets, have exhibited a high correlation, especially in recent years. It appears that there are common risks within this crypto universe, which we will explore in more detail in the next section.

Common Risk Drivers Across Crypto Assets

Turning back to the 10 coins examined in Exhibit 6, we use this group to run a Principal Components Analysis (PCA), which extracts uncorrelated principal components (PCs, or statistical risk factors) from the coins’ covariance matrix.20 PCA reduces the dimensionality of large data sets (in our case, a 10 by 10 covariance matrix) to a handful of PCs that convey important patterns or common risk drivers across the data. The PCs are fully data-driven and say little about economic intuition, thus making the underlying risk less clearly identifiable. However, this analysis will tell us the extent to which there are common risks (how many there are, how influential they are, etc.) across this crypto universe.

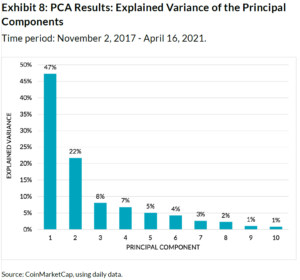

Exhibit 8 shows that, together, the first two PCs explained ~69% of the variance. The first PC was much more explanatory, covering roughly 47% of the variance, while the second PC covered ~22%. The rest of the PCs explained 8% or less of the variance each. To put these results in context, we can compare them to the PCA results of traditional macro assets. For example, a PCA on the U.S. yield curve finds that 99.9% of the variance can be explained by the first three PCs.²¹ And a PCA of the equity index returns of eight European countries shows that the first two PCs explained >90% of the variance.22 So, while there were two major risk drivers in this seemingly diverse crypto market, when compared with more traditional assets, the first few PCs weren’t as explanatory.

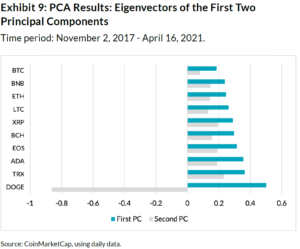

Let’s dive into those first two crypto PCs in more detail. As mentioned earlier, PCs are difficult to put economic intuition behind, but we can look at the portfolio weights for each PC (as denoted by their eigenvectors) to understand their constructions. Exhibit 9 displays those portfolio weights (eigenvectors) for the first and second PCs. The first unnamed risk factor is unsurprisingly long all of the coins (note that the sign of the eigenvectors does not matter), representing what might be considered “crypto beta.” The second PC is a bit more interesting. It appears to be capturing the unique risk of DOGE relative to all of the other coins. This brings us back to the correlation matrix in Exhibit 6 where we noted that DOGE was the most diversifying coin with an average correlation of only 25%.

Conclusion

Crypto has been gaining a lot of attention recently. There are many ways to obtain crypto exposure, including by investing directly in coins on centralized and decentralized exchanges, through derivative instruments like swaps and futures, and via stocks that are investing in blockchain technology.

Unfortunately, it can be difficult to understand the risks of crypto assets using traditional financial risk models. For example, analyzing Bitcoin using the Two Sigma Factor Lens shows a large, idiosyncratic risk. That being said, Bitcoin was not entirely orthogonal to the factor set–there did appear to be some meaningful relationships with existing risk factors, such as positive correlations with the global equity market and the tendency for BTC to behave like an inflation sensitive asset.

Of course, Bitcoin is just one coin in the crypto space. In this Street View, we explored the extent to which crypto assets are diversifying among themselves. We found that the 10 largest coins by volume are all positively correlated, with DOGE exhibiting the lowest average correlation. Given these positive correlations, we analyzed whether there are shared risks across crypto assets. A PCA also revealed that there were two major risk drivers across these coins over the past few years: long crypto (i.e., crypto beta) and unique risk of the most diversifying crypto asset in the 10-coin universe (DOGE).

In summary, crypto appears to be a highly volatile, yet diversifying asset to portfolios with exposure to traditional risk factors. There does appear to be meaningful relationships among crypto assets, suggesting that a portfolio diversified across many coins might not reap massive diversification benefits.