On a summer’s day in 1962 a nun in her mid-40s went to see Andy Warhol’s breakthrough exhibition of soup can paintings; later, she recalled that “coming home you saw everything like Andy Warhol”. It was a seminal moment in the transformation of Sister Corita Kent from a convent school teacher into the artist who became known as the Pop Art nun.

Among the many original, mould-breaking, stand-alone characters the art world has produced, Kent more than holds her own. A fully habited nun, complete with veil and wimple, her monochrome outfit was a stark contrast to the vibrancy of her colour-charged silkscreens, which burst with the kind of joie de vivre, risk-taking and trenchant politicisation that seems to sit strangely with a woman who had made a vow of obedience. That was certainly what some of her church superiors felt; they denounced Kent’s work, forcing her to leave her religious order. But she didn’t leave art; and this year, 100 years on from her birth, that is being remembered with an exhibition of her work at Ditchling Museum of Art and Craft in Sussex.

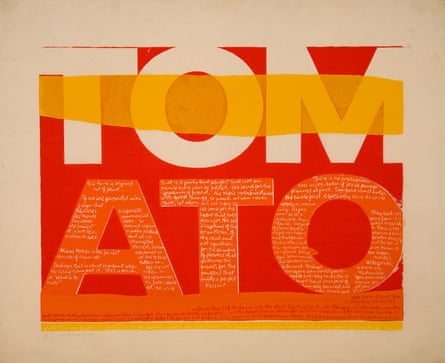

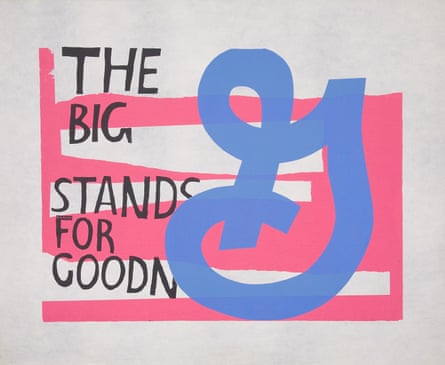

According to Donna Steele, the exhibition’s curator, Kent’s work is “as important as that of Warhol” to the Pop Art movement. “It stands up there with the work of the Pop Art greats – people like Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Richard Hamilton and Peter Blake. It’s big and bold and it’s of the moment.” Kent used advertising slogans and song lyrics, as well as biblical verses and quotes from literature, to create vibrant silkscreens with trenchant political messages about racism, poverty and injustice. “What you get is this visual feast of twisted text and messages, and the more you look, the deeper you realise the messages go,” says Steele. “She picked up on everyday language and advertising slogans – this was the 1960s, and consumer culture was exploding; she used words like ‘tomato’, ‘burger’ and ‘goodness’ and she made them into messages about how we live, and about humanitarianism and how we care for others.”

The Ditchling exhibition covers Kent’s output across two decades, 1952-72, probably her most important period in terms of her story as well as in her output. Born Frances Kent in November 1918, the fifth of six children, her strongly Catholic family moved from Iowa to Hollywood in 1923. At school there, her art work was praised for its originality; and at the age of 18 she entered the order of nuns whose school she had attended, the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. There, in their convent in Los Angeles, her artistic talent was picked up by one of the senior nuns, Sister Magdalene Mary, who encouraged Kent to train as an art teacher. She went on to work in the order’s college, a liberal arts institution well known for its avant-garde views, and became head of its art department in 1964.

Los Angeles in the 60s was an exciting place at a momentous time: Kent’s work brought contact with figures such as filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock, composer John Cage, architect Buckminster Fuller, and designers Charles and Ray Eames, who became her close friends and champions. Her work became more prominent, and in the winter of 1967 she was featured on the cover of Newsweek – ‘The Nun: Going Modern’, read the strapline. The nun was indeed going modern; and for a while, it seemed the institution she was part of, the Catholic Church, was going modern, too. In 1962 – the same year Kent saw Warhol’s soup cans – Pope John XXIII was convening Vatican II, the great reforming council that many liberal Catholics, like Kent and her community, thought would bring the Latin-using, medieval-rooted church into the 20th century, making it relevant and liberal; Christian, as Kent would have seen it, for the 20th century.

It was against the backdrop of this great reforming movement taking place in Rome, alongside the seismic changes in popular culture of the secular 60s, that Kent embarked on her most exhilarating work. Tame It’s Not (1966) quotes from Winnie the Pooh and Kierkegaard, as well as the ad slogan for a men’s cologne, and includes an aeroplane which many see as a reference to a guardian angel; “Somebody up there likes us”, reads one of its hopeful messages. More political is stop the bombing (1967), her protest against Vietnam, with blue text against an angry red background; more religious is enriched bread (1965), which uses an everyday loaf (“Helps build strong bodies 12 ways”) to reference the Catholic Mass, and the importance of the Eucharist. Words sing out of Kent’s silkscreens, their simplicity often belying the complexity of their messages. “It’s colourful and it’s captivating, and you can see her work just in those terms,” says Steele. “But if you want you can get more: she is so well-read. She’s not just making work, she’s having a fight through her work: she’s fighting because she believes in the fundamentals of Christianity.”

It’s as a nun that Kent is at her most intriguing. According to Ray Smith, director of the Corita Kent Center in Los Angeles, where her work and her memory is celebrated and preserved, there was a gulf between her work and her personality. “Her work is expressive, exuberant, loud, boisterous – but that contrasts with her own personality, because she wasn’t loud. She had a quiet intensity, and she was quite a private person.” Lenore Dowling, 86, was a nun of the Immaculate Heart of Mary order at the same time as Kent and worked with her at the college; though a generation apart, she says the two of them shared a similar background. “Like Corita, I’d been at school at the convent, and I was influenced, and Corita quite probably was, too, by the fact that the nuns who taught us were so young, in their early 20s, and they were so enthusiastic; joining the order seemed a very attractive future.”

Like Kent, Dowling remembers the excitement around Vatican II, and the hopes for lasting, liberal changes in the Catholic Church. But the Archbishop of Los Angeles, Cardinal James McIntyre, was a diehard traditionalist who disapproved strongly of the views of the nuns of Kent’s order, and particularly of the art of Kent herself. He took particular offence to a piece called the juiciest tomato of all (1964) in which Kent likes the Virgin Mary to a luscious tomato. The following year, McIntyre wrote to the head of the order to complain that “The Christmas cards designed by your art department and the sisters are an affront to me and a scandal to the archdiocese.”

Kent tried to brush off the criticism, but coming from such a prominent figure in the church made it hard. In the summer of 1968 she took a sabbatical, spending the summer in Cape Cod; at the end of that time, she decided it wasn’t possible to go back to the convent. “It wasn’t only because of the tension of the backlash from the church,” says Dowling. “Corita had also been getting very little time for her own creative work. I think it all added up, and she realised she needed more time to herself, rather than running a busy art department.” Many other nuns, women who like Kent (and Dowling) were liberal Christians, also left the order around the same period; they established a much broader, more inclusive kind of religious community and Kent remained close to the new group until the end of her life, eventually leaving her work and royalties to them.

But from the age of 50 she lived alone, for the first time in her life, moving into an apartment in Boston. From now on her work becomes quieter, includes nature-inspired watercolours, and reflects her search for meaning from other religious traditions as well as pieces that reflect her experience of cancer, with which she was diagnosed in 1974 and again three years later. The yellow exuberance of live the moment light and out of the darkness (both 1977) speak movingly of her struggles in this period: “Out of the darkness/of one moment/grows the light/of another moment/perhaps in some distant time/if not in the next moment/love the darkness” are the words on the latter piece.

Steele’s view is that Kent, who died in 1986, was able to pour all her emotion into her art because of the life choices she made. “As an artist she was all emotion, but because she chose to be a nun, to be a single woman, not to have children, she had no lovers or children to take up that part of her.” What, though, of her legacy? “Some of the graphics were of their time: but the messages are still very relevant today,” says Steele. Kent knew the power of a few well-chosen words, and in the world of text-messaging and Twitter, a world she never knew, that has a particular resonance. Perhaps most significant of all, though, is her belief in activism. We live in a time when popular action seems complicated and confusing; and Kent’s simple, heartfelt message rings down the decades. Because for her, there is no doubt about it. Feelings, and owning feelings, really can change the world.

Corita Kent: Get With The Action is at Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft, 5 May to 14 October (ditchlingmuseumartcraft.org.uk)

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion