South America's Otherworldly Seabird

To save the tiny seabird, scientists are venturing to its secret home in the Atacama Desert—and sticking their noses into a lot of stinky holes in the ground.

The peninsula northwest of the industrial city of Antofagasta, on Chile’s northern desert coast, is haloed with seabirds in flight. Pelicans lumber past wheeling gulls. Flocks of boobies cut the haze around Punta Tetas—Tits Point—like an avian punch line.

Farther from shore, where the inappropriately named Pacific begins its wild pitch and yaw, is the domain of the order Procellariiformes: birds with long, hooked bills and tubular nostrils that spend most of their lives above the open ocean. The largest of these are the albatrosses, soarers with severe brows and stiff, straight wings that span several feet. The smallest—small enough to hold in one hand—are the storm petrels. Most of the storm petrels that ply the air off this coast are brownish black, with crescents of lighter feathers across their shoulders and the erratic flight patterns of a bat. When they drop to the water’s surface to dip mouthfuls of food, they seem to run across it. This habit inspired the name of the birds’ original taxonomic family, recently split into two: Hydrobatidae, meaning “water walkers.”

The Spanish name for storm petrels is golondrinas de mar, or golondrinas de la tempestad—“swallows of sea,” “swallows of storm.” Sailors of old thought they heralded bad weather, and called them “Mother Carey’s chickens,” emissaries carrying warnings from the Virgin Mary or ship-sinking gales from darker spirits.

Among these far-flying little birds, one can be particularly difficult to find: the ringed storm petrel, or Oceanodroma hornbyi. It has dark wings with white half-moons, like the other petrels here, but its face and belly flicker bright white, and it sports a collar and a rakish masked cap of dark gray. While the other storm petrels seem abundant, the ringed arrives alone, and is gone quickly: a dipping turn like a wink, then away. It rarely appears less than 30 miles from shore, and ranges 300 miles farther out, where gossamer flying fish launch from wave faces like butterflies and the seafloor plunges thousands of feet.

To a storm petrel, the U.S. naturalist and author Louis J. Halle once wrote, the continents are a “mere rim for the once great ocean that envelops the globe.” This ocean is its own landscape, divided by changes in temperature, salinity, wind, and other factors into different habitats. Ringed petrels find theirs in the cold, nutrient-rich Humboldt Current that flows north from the southern tip of South America along the Chilean and Peruvian coasts. They spend so much of their lives over the Humboldt that they’re considered endemic to the current: more native to moving water than to earth.

Even so, the birds must eventually alight on solid ground to raise their young, and on land they’re even harder to find. Like most seabirds, storm petrels often nest in extreme terrains, such as remote islands and seaside cliffs, which protect brooding adults, eggs, and chicks from mammalian predators. They tend to travel overland only at night, and hide in crevices by day.

For more than 150 years, the ringed storm petrel’s breeding grounds remained a mystery. Then, in April of 2017, a group of volunteer naturalists found the world’s first documented nests. They were 45 miles inland from the Chilean coast, deep in the driest nonpolar region on Earth: the Atacama Desert.

The contrast between the open ocean and the Atacama sounds remarkable. What could be more different than a great expanse of water and a great expanse of none? But if the ocean can be a landscape, the Atacama can be a sea: It stretches for 600 miles through northern Chile, a narrow north-south strip bounded by coastal mountain ranges and the foothills of the Andes.

In austral summer, while the ocean’s horizons are riffled by waves, the Atacama’s are riffled by heat. In afternoon and evening, the coastal ranges on the desert’s edge turn blue as surf. Sometimes, as night falls, a froth of ocean-borne fog called camanchaca breaks over the earth, making the mountains into islands. And with the darkness come the birds of the sea.

That’s the hope, anyway, on the chilly January midnight that two red Toyota HiLux pickups roll to a stop in the desert outside the sleepy town of Diego de Almagro, 250 miles south of Antofagasta. Fernando Medrano-Martínez twists to look at me in the back seat of the second truck. “We’re here,” he says.

“Here” in this case might better be described as “nowhere,” a plain of floury dust scattered with sharp rocks and bordered by a towering transmission line. But if Medrano-Martínez and the other four birders from Red de Observadores de Aves y Vida Silvestre de Chile—the Chilean Bird and Wildlife Observer Network, or ROC for short—are bothered by the lunar scene, they don’t show it.

Medrano-Martínez, 29, who is tall with taped-together hipster glasses and curly black hair, and Patrich Cerpa, 32, who is never without a handheld vacuum for collecting insects, banter in Spanish as they shove a drift of toffee wrappers into the glove box and hop out. On the tailgate of the other truck, Felipe de Groote, a veterinarian turned environmental consultant, and Ronny Peredo-Manríquez, a marine biologist and ecology professor, rummage through bags of food. Rodrigo Barros—a silver-bearded architect and the leader of our endeavor—coaxes forth a flame from a mound of charcoal in a crude fire pit to cook a skein of sausages and five platter-sized steaks.

ROC is a grant-funded group with about 250 members that broke away from the more academic Union of Chilean Ornithologists in 2009. Barros and the other founders, Fabrice Schmitt and Fernando Díaz, envisioned an organization that would embrace both amateur and expert birders, and help foster public interest in natural history. ROC made Chile a global pioneer in the use of eBird, a citizen-science website overseen by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology that allows people to add bird sightings to what is now the largest biodiversity dataset in the world.

“There was this rebellion of younger birders,” says Alvaro Jaramillo, a Chilean raised in Canada and the author of the Princeton Field Guide Birds of Chile. “They had all these questions, you know”—about distribution, migration, and where and why birds did certain things. In Chile, where ornithological research has been spotty, there were plenty of options for inquiry, and the mysterious petrels of the Humboldt Current offered some of the most intriguing questions.

In addition to the ringed, the Humboldt was home to two other largely unknown storm petrels: the Markham’s and the Elliot’s. When ROC was created, just one Markham’s breeding area had been discovered, in Peru, and one Elliot’s colony, on a Chilean island. But both birds were too abundant for those to be their only nesting ground.

In June of 2013, the storm-petrel mystery began to crumble. A tip from an entomologist studying bees led a pair of Santiago-based ornithologists to the desert near the city of Arica, where they found Chile’s first-recorded nests of the Markham’s, a delicate, brownish-black bird.

Around the same time, an environmental consultant surveying an Atacama salt flat south of Arica heard the machine-gun-fast chitter of an unknown bird. She sent the call to an online birding forum, which passed it on to Jaramillo. Jaramillo tipped ROC off and that November, ROC birders, including Barros, Medrano-Martínez, Peredo-Manríquez, and de Groote traveled from Santiago, Arica, San Pedro de Atacama, and elsewhere to visit the spot. They found the remains of a dead chick and heard live ones peeping beneath the ground, along with footprints and scattered wings. When Barros and Peredo-Manríquez returned the following April, they caught adult Markham’s storm petrels singing the breeding song. There was “not only one bird, but more than 100 of them,” Barros says, “all of them screaming at the same time.”

The finds made the men curse with joy and hop around like children. They had discovered Chile’s second known concentration of Markham’s nests, tucked into the knife-sharp pockets and cavities that formed in the surface of the salt flat, or salar. They resolved to search the Atacama for Elliot’s- and ringed-storm-petrel breeding grounds too, along with those of the better-known wedge-rumped storm petrel. The ROC Desert Storm Petrel Project was born.

Their quest, they came to realize, was urgent: Industry was transforming the Atacama. Chile supplies one-third of the world’s copper, and metal and salt mines had long chewed through the desert. More recently, strong incentives had spurred a wave of renewable-energy construction. Solar-power installations sprawled across the emptiness, wind turbines prickled horizons, and every new project brought more electrical lines, more roads, and more people. Because storm petrels tend to nest in densely populated colonies, any one of these developments, if poorly placed, had the potential to devastate great swaths of irreplaceable breeding ground—by destroying cavities, cutting off key paths to the sea and its bounty of food, or even killing birds directly.

Industrial and urban developments also pierced the desert darkness with more and brighter lights. No group of seabirds is as vulnerable to light pollution as the burrow nesters among the Procellariiformes, which are disoriented by the artificial glow, perhaps because they rely on the moon and stars to navigate at night. Each year, when storm petrel fledglings made their first flight west to the sea, many plunged into Chile and Peru’s illuminated desert and coastal communities, a phenomenon called fallout.

The young birds collided with buildings or landed exhausted in streets, backyards, and mines. Once grounded, they were vulnerable to dehydration or starvation, being hit by cars, or being eaten. At one brightly lit salt mine, turkey vultures picked off so many that downy wings collected in piles below the lampposts. Another salt mining company recorded 3,300 Markham’s fledglings grounded by its lights in a single three-month period.

For millennia, the Atacama’s harshness had helped keep the storm petrels safe. Now the obscurity that accompanied the birds’ isolation had become a grave threat to their survival. Because the birds’ conservation status was unknown, they received only limited direct protection through Chile’s hunting law, which by many accounts is difficult to enforce. And the salt substrate that the Markham’s preferred was not represented in any of Chile’s existing preserves. Finding more colonies, ROC’s birders reasoned, was the only way to grasp population size, document threats, and set in motion efforts to save key habitats.

Over a dozen field trips, ROC began to piece together a sketch of the Markham’s breeding grounds and paths of movement. There seemed to be three colonies stretching between the cities of Arica and Iquique, totaling at least 130,000 birds. The largest contained five subcolonies, which appeared to be linked to the sea by a single creek corridor. At its mouth, in 2016, ROC birders arrived in time to spot a tide of perhaps 10,000 Markham’s storm petrels sweeping overhead, dark flashes against a darkening sky.

By March of 2017, ROC and others had collected enough information for the government to consider reclassifying the bird from “insufficiently known” to “endangered.” The change, which went through in late June, will bring public leverage for conservation along with a plan for accomplishing it, a gain for the birds’ protection that hints at what might be possible for the ringed storm petrel. If someone could only find more of them.

From the beginning, the ringed storm petrel had been veiled in both mystery and misdirection. According to the late U.S. ornithologist Robert Cushman Murphy, an authority on South American seabirds, the specimen that scientists used to define the species, collected in 1853 and kept in a British museum, was unlabeled and believed to have originated “from the northwest coast of America”; in 1887, a U.S. naturalist claimed to have seen ringed petrels off Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. A Chilean museum acquired two immature ringed storm petrels from deep in the Atacama in 1895, but identified them as a different species.

By the time ornithologists recognized that the ringed petrel was tied to the Humboldt, reports of mummified birds surfacing from the Atacama’s chalk-white nitrate mines had them looking to the desert. And later, the ringed storm petrel fallout in Antofagasta and other desert communities also pointed searchers toward inland breeding grounds. In 1999, a British ornithologist named Michael Brooke looked high and low in the Atacama for a month, but found nothing. “He said, ‘I can do that. I will find them,’” an Antofagasta-born biologist named Carlos Guerra-Correa, who hosted Brooke at his house, told me. “But the desert is not so simple.”

At the time, Guerra-Correa was also searching for ringed-storm-petrel nests. In 1998, he had started a rescue program for light-dazzled storm petrels at the University of Antofagasta, where volunteers hydrated them with a mix of water and fish oil, then released them by night from a seaside cliff. Guerra-Correa and his students recorded when each of these birds arrived and where it was found, and they mounted hundreds of trips to the Atacama. They fared little better than Brooke.

What the ringed-storm-petrel searchers needed was a clearer clue. And deep into their Markham’s research, the ROC birders got one. Late in 2016, an environmental consultant named Rodrigo Silva was surveying the desert for a solar project near Diego de Almagro and found some strange holes in the ground. Silva, also a ROC member, suspected that the cavities belonged to storm petrels, but they were located in rolling hills, not in salt flats like the Markham’s nests. A few months later, Medrano-Martínez, Barros, de Groote, and ROC’s executive director Ivo Tejeda used their own money to mount a brief, three-day expedition to the place.* Each night, they strung fine-mesh nets over several cavities and checked them hourly, but without luck. Finally, early on their last morning, they caught a single bird. It was unmistakable: white and dark-gray feathers ruffled from entanglement, scythe-shaped wings, liquid-black eyes. A ringed storm petrel.

Now the team—clad to the man in zip-off synthetic field pants—is back to get a better idea of the size of the nesting grounds Silva found. They hope to gather information about the habitat that will help them search for more ringed-storm-petrel nests farther north, where populations are likelier to be denser, over the next 10 days. “The intrepid explorers!” I comment. Barros snorts, looking out over the barren landscape and its blowing clouds of dust. “More like explorers who are sick in the head!” he says. Then, later, more seriously, “It’s the only rational thing to do.”

“To know the unknown things,” Peredo-Manríquez interjects. “To understand the unknown.”

The work of solving Chile’s most intriguing ornithological mystery, I quickly discover, boils down to searching not just for holes, but for stench. Storm petrels waterproof their feathers with strong-smelling oil produced by a gland at the base of their tail. They also process their marine meals into a concentrated fishy oil, which sometimes slops around when they cough it up to feed young. The combined odor, a cross between human armpit tang and sunbaked horse manure, clings to the earth even when the petrels aren’t home, making it a cheap, quick way to confirm recent use.

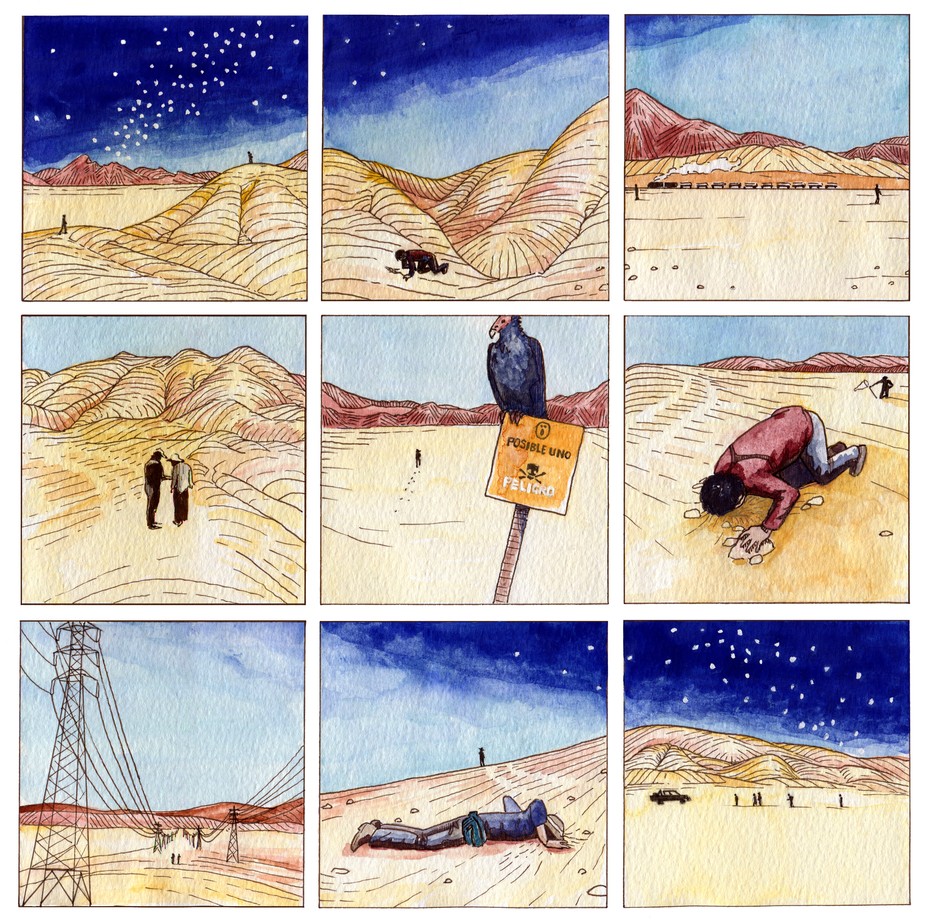

The 25 smelly petrel cavities that ROC documented last April correspond with a specific geologic formation, so the birders use a rough map of its extent as a guide and split into teams to cover more terrain. We steer up washes, jostling over two tracks left by mining prospectors. We pause when we see promising ground, striking out on foot over crust that looks like it will hold our tracks for millennia, sniffing holes when they appear. From a distance, the birders look like they are praying, or kissing the earth. Medrano-Martínez kneels. Cerpa lies belly down, as if flattened by the sky. Within a few days, we have stuck our noses into hundreds of holes. Dozens of them are redolent of petrel, making the trip, so far, a qualified success.

Medrano-Martínez and Cerpa are exactly the sort of natural-history buffs that Barros hoped ROC would attract—young, enthusiastic, and more interested in connections among creatures and landscapes than they are in racking up species sightings. Cerpa is working on a master’s degree in entomology, and carries a butterfly net like a flag. Medrano-Martínez wears a pair of high-end binoculars made by Swarovski—a crystal-jewelry company—the way others might wear a favorite T-shirt: casually, and all the time. When he joined ROC to take a bird-banding class, he was a 19-year-old sustainability-engineering student who played bass in an indie rock band called Biota Marina. Now, the bass is gone, and Medrano-Martínez, who just finished his biology master’s degree, is one of ROC’s only paid staffers, working part-time to turn eBird data into Chile’s first breeding-bird atlas.

In conversation, Medrano-Martínez and Cerpa shift seamlessly from music and “the nihilism of Chilean football” to Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene, the book that both credit with helping them begin to think like biologists. Their conversation is peppered with asides about Chile’s wilder residents: a vampire bat that shares blood meals with its colony neighbors; the country’s lack of social wasps; an Atacama songbird that Medrano-Martínez speculates may be supported by the marine nutrients brought by petrels and other travelers.

Each dusk, the two teams of birders convene to discuss their finds over cans of beer, which de Groote has chilled by wrapping them in wet toilet paper and wedging them against the HiLux air conditioning. Storm-petrel species tend to return to the same place, and even to the same mate, to breed each year. If ringed storm petrels do so, the birders wonder, how do they find the exact right hole in this desert vastness? And how do they hit it again and again, after round-trip ocean-foraging journeys covering hundreds of miles? Through darkness? Through fog?

Perhaps they’re like us out here, de Groote muses. After getting in the right neighborhood with visual cues, they follow their noses.

Or they follow their ears. ROC’s birders scheduled this expedition during the January new moon, hoping to once again hear newly arrived storm petrels singing for mates and territory. They planned to record the ringed petrel calls and play them into holes, provoking any rivals inside to sing—a more definitive way to confirm the birds’ presence and identity and thus the bounds of known and new colonies.

But the only thing making holes sing here is the wind, which sometimes shrieks through notebook coils and moans across water-bottle mouths. This silence is the first sign of trouble.

We depart the colony at Diego to follow the geologic formation north into new basins. “Now,” Barros tells us expansively over yet more steak, “we will catch a storm petrel every night. It is a requirement.” Instead, we lose all sign of them. First there are only cavities without smell, and then there are no cavities at all.

The night fog vanishes, and the days cook. We walk on the dark tails of our own shadows under the relentless sun, tracked by circling turkey vultures. “We’re not dead yet!” Cerpa yells at the sky. What sparse vegetation there was near Diego is absent here, along with the bugs it hosted, so Cerpa’s net wilts, forgotten, in the HiLux. Once, Medrano-Martínez and I strike out in opposite directions, only for Cerpa to call us back, wildly waving his arms. He points out a row of Peligro! signs we’ve missed, marking some serious danger we can only guess at.

We check hill crests and flanks; we check forever-stretching flats. Each team shreds a tire and drops to a single spare. Ominously, we find a graveyard of wooden crosses, and step carefully across shattered crockery, the wire hoops of old wreaths. A shard of human skull and the twig-thin ribs of a toddler lie exposed on the dirt, scoured from their broken tombs by the wind.

Just as the seemingly featureless ocean is divided by salinity and temperature, this landscape is demarcated in ways that the birds recognize, but that the birders do not. “We are lost,” Barros says one night in camp. “We are learning to see.” We are, it seems, chasing phantoms. The land blurs with mirages, pools of water that vanish as we near. “Espejismo,” de Groote tells me when I ask him the word—literally “mirror-ness.”

Medrano-Martínez, Cerpa, and I drive through a long-abandoned nitrate mine, a valley where every inch of earth seems to have been dug up and turned over. We’re pessimistic about its potential for birds, but get out anyway, our feet sinking in powdery earth up to our shins. Cerpa picks up a crushed rusty bucket, drops it again. If there were ringed storm petrels here, they’re decades gone.

Medrano-Martínez climbs back into the driver’s seat.

“Shit,” he says.

“Mierda,” I say, trying out the Spanish word.

Cerpa opens a bottle of Coke, which fizzes in the silence. “Mierda,” he says, more softly.

By the third-to-last day of the ROC expedition, the team is haggard and still bird-less. We’ve replaced the spare tires, and some of us have changed our shirts, but dust has coated everything else—our bags, our food, and the HiLuxes, one of which now bears a finger-drawn outline of a ringed storm petrel. The bird looks jaunty and a little smug. The wind roars, blowing unlikely objects across the cracked hills.

“Look, there are pants,” I say to Medrano-Martínez.

“They are Patrich’s,” he says with a straight face.

“They are not mine,” Cerpa replies.

“Have you checked?” I ask.

“Yes,” he laughs. “But at this point, anything can happen.”

Indeed so, for the other team, checking another tip from an environmental consultant, calls to tell us they have discovered some smelly holes in a salt flat east of Antofagasta. It appears to be a habitat where we might find a Markham’s-storm-petrel nest, a consolation prize of sorts, but Medrano-Martínez says we’ll need to catch one in a hole there to be sure. We meet up with Barros and his crew at a truck stop, then leave the road and bounce overland, following their rooster tail of dust to the site as the valley pools with shadow.

That night, the Southern Cross rises on its skew of Milky Way and the men listen openmouthed to birdsong that rises from beneath the ground. They set squares of black net across three cavities, anchored at their corners with metal stakes. Every hour until midnight, we check the nets. And every hour, we find them empty. But the later it gets, the more the earth cries out. A frenetic chatter to the west, then fainter to the east, then stronger to the northwest.

Finally, exhausted, the men move the trucks to form a windbreak so we can set up our tents and check the nets in shifts. As I grab my pack, there is a commotion. “Golondrina!” de Groote yells, in a disbelieving voice. All headlamps swivel skyward, and there it is. Not an all-black Markham’s, but what appears to be a smallish white-and-gray bird dodging in and out of our beams. It leaves, then returns, then leaves again, an avian ricochet.

After all those brutal days of searching, we have failed to find the ringed petrel. But the ringed petrel has found us.

Two hours later, we see two more ringed petrels, swooping low over one of the singing holes. This time, de Groote gets a photo that shows the bird’s characteristic gray collar, cap, the dark undersides of its wings, and its white face and white belly—clearing doubt that what we are seeing is a trick of the light reflecting from the Markham’s glossy plumage. At 3 a.m., we spot little tail feathers poking from a net. We rush toward the captured bird, believing for a moment that it will confirm for us what some of the birders have begun to hope: that these holes belong to our airborne visitors; that here in this stark valley, at last, is a brand-new ringed-storm-petrel breeding ground, hundreds of miles north of where we started.

But the dark bird that stares up at us is, in fact, a Markham’s. Medrano-Martínez purses his lips, then lifts it carefully from the net and gently upends it in the cradle of his hand, blowing on its chest. There, beneath soft black feathers, is a bare patch of skin that allows for an easier transfer of heat. The bird is incubating an egg, and it seems more than ready to get back to that task, kicking at Medrano-Martínez’s fingers with black webbed feet little bigger than thumbprints.

As in so much biological inquiry, the birders have found not answers but more questions. Could the two species form mixed colonies? Or were the ringed petrels we saw bound for nests elsewhere? Reinvigorated, we fan back into the hills, searching for endpoints of possible flight paths. It takes two days, but we find a single stinky hole, high on a barren slope, that resembles the ringed-storm-petrel cavities near Diego. Cerpa, Barros, and I take the 2 a.m. check. The burrow appears, a dark absence. Light from our headlamps finds and pools over its edge. In its glow, a blur of white and gray feathers. “We have it!” Cerpa cries.

But as before, we don’t. The ringed petrel is behind the net. We approach and it recedes back into darkness—again, just beyond reach.

It doesn’t matter so much. The sighting is enough to tell ROC that the bird is nesting here, useful information for future surveys. We’ll still try to get a photo for publication. Barros is elated. “It’s perfect,” he says, “because this is our last night!”

By dawn, there has been no more sign. Medrano-Martínez and I drive toward the burrow on tracks streaked over with the dust of our somnambulant journeys. The net is empty. He folds it into a drawstring bag and we turn back.

The horizons pinken and Medrano-Martínez talks about some of the things that still need to be done for the birds. Tapping a geologist’s expertise to better understand the nesting substrate, more expeditions, recommendations for light regulations, keeping tabs on the potential solar project near Diego. Meetings with industry, communities, and government to help protect the Markham’s. In a few weeks, Medrano-Martínez will learn that managing some of these tasks will fall to him: He’ll be the first paid coordinator of the Desert Storm Petrel Project, sharing the position with Barros as the organization begins to find its feet as a more formal conservation group. And in March, the ringed-petrel mystery will crumble a little more, when the Antofagasta biologist Guerra-Correa at last finds the nesting site of what he believes to be 40 of the birds—opening up possibilities for studying physiological traits and behaviors that help these seabirds manage the desert’s extreme heat.

Right now, though, Medrano-Martínez knows none of this. He’s just tired. He rubs his eyes and smiles sheepishly as he lets me off at my tent. “Are you going to sleep again?” he asks me.

I nod.

He blinks at the sea-blue hills. “I will not sleep,” he says.

*This story has been updated to name everyone who took part in the expedition.

This article is part of our Life Up Close project, which is supported by the HHMI Department of Science Education.