Is Taiwan Next?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine makes the frightening possibility of China seizing control of the island more real.

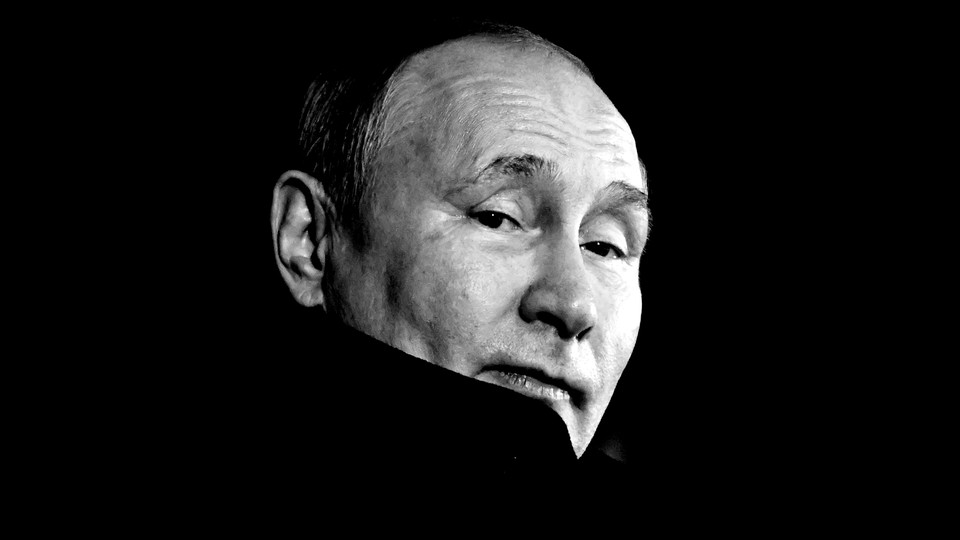

As Russian tanks roll over Ukraine, Vladimir Putin’s crisis will reverberate around the world, possibly most dangerously in the Taiwan Strait. An attempt by Beijing to claim Taiwan by force has just become more likely. That’s not necessarily because there is a direct link between Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and Beijing’s menacing of Taiwan, but because the war for Ukraine is the most unfortunate indication yet of the frightening direction of global geopolitics: Autocrats are striking back.

With the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, the long American struggle against global authoritarian threats seemed to have been won. Just about everywhere, dictators were on the run—Indonesia, Myanmar, Brazil, South Korea, the Philippines, Chile, and even Russia itself. Globalization was working its supposed magic, spreading liberal political and economic ideals, prosperity, and, hopefully, an end to big-power confrontation. Sure, the Chinese Communist Party was entrenched in Beijing, but its cadres appeared to be partners in the global order, content to get gloriously rich and immerse themselves in the trading networks and international institutions created by the democratic powers.

Putin’s Ukraine war exposes how wrong that line of thinking was. What the U.S. and its allies achieved in the 1990s was not a final victory over authoritarianism, but a mere respite. For years, the American-led liberal democratic consensus has been eroding: Take Viktor Orbán’s illiberal democracy in Hungary, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s undercutting of freedoms in Turkey, or Narendra Modi’s assault on India’s secular traditions. In Myanmar, the generals have reclaimed control; Jair Bolsonaro espouses antidemocratic rhetoric in Brazil; and Rodrigo Duterte has proudly prosecuted a violent and lawless drug war in the Philippines. Still, Putin’s invasion marks a new stage, heralds a new era—one of authoritarian aggression.

No country, though, is as big a threat to the liberal world order as China. Russia, in many respects, is a declining power, lacking the economic dynamism to sustain its political punch. The assault on Ukraine may be Putin getting what he wants while he still can. The story is different with China—a power with increasing economic, diplomatic, and military might. Russia is in the headlines today, but China will be the spearhead of the authoritarian cause. President Xi Jinping’s nationalist fervor, commitment to the restoration of Chinese power, and more aggressive approach compared with his predecessors when it comes to territorial and maritime disputes, relations with the U.S. and its allies, as well as the international system writ large, have already become a destabilizing force in Asia.

Taiwan is on this tenuous front line. Just as Putin can’t tolerate Ukrainian sovereignty, the Chinese Communist Party will never accept the separateness of Taiwan, which Beijing considers a core part of China occupied by an illegitimate (and by the way, democratic) government. Gaining control over Taiwan, or as the party prefers to call it, “reunification,” is a primary goal of Chinese foreign policy. In a world order where authoritarian states are more assertive and democratic allies are on the back foot, the chances of war over Taiwan increase. Xi has already been intimidating the government in Taipei by sending squadrons of jets to harass the island, while Beijing’s complete suppression of the prodemocracy movement in Hong Kong undermines any hope that Taiwan would retain a semblance of its current freedom were it to be incorporated into Communist Party–led China.

That doesn’t mean a Chinese attack on Taiwan is imminent. It is impossible to predict with certainty what Xi may be thinking about Taiwan in the aftermath of Putin’s Ukraine war. Unlike Putin when it comes to Ukraine, though, Xi isn’t amassing an invasion force on the strait separating Taiwan from the Chinese mainland. Also, Xi is many bad things, but foolhardy is not one of them. In his perception, China’s ascent is inevitable; time is on its side. He has no need to follow Putin on the path to war.

But Putin’s military aggression is a sign of what may come. Authoritarian powers believe the moment has arrived to push back against the U.S. and reshape the world. And who’s to say they’re wrong: It is not at all clear if the democratic allies have the will, resources, or unity to fight another battle with autocracy. The Ukraine crisis has shown both how the U.S. and its allies in Europe strive for common purpose, while nevertheless falling short in terms of garnering results. Europe’s leaders want to chart their own course, but their much-touted “strategic autonomy” is looking more and more like “strategic indecision,” in which short-term economic and political gains take precedence over long-term strategic interests. In Washington, meanwhile, rabid political divisions raise serious doubts about continued American resolve. The U.S. public is weary of fighting the world’s battles.

If these trends continue to unfold, the day when China invades Taiwan gets closer. Chinese leaders are coming to see American decline as inevitable, as much as their own rise; the Ukraine crisis may appear to add even more evidence to their case. One day, they may calculate (or worse still, miscalculate) that the U.S. and its partners won’t fight for one another, their ideals, or their world order.

Nothing, though, is inevitable. Washington’s critics will complain that the failure to prevent Putin’s invasion is already a sign of creeping American weakness. But the U.S. has never been, and will never be, omnipotent. The fact is that the Ukraine game is not over. Now the world—and especially Xi Jinping—will be watching to see how much pain and cost the U.S. and its allies can and will inflict on Russia. The U.S. has projected its power not merely with aircraft carriers, but with its technology, its currency, and its talent for organizing collective action. Putin’s assault on Ukraine is a test for all of these many tools.

China and Russia are certain to keep the pressure on. They’ll foment new crises to press the U.S. and its partners. Perhaps the alliances can be broken and American primacy eroded.

The modern world, with its integrated links of economic and security interests, is too complex to be defined as a simple contest between democracy and autocracy. But it can be divided between those states that benefit strategically from the perpetuation of the current world order, and those that gain from subverting it. The Ukraine invasion could be just one stage in a campaign to destroy it. The next one may well involve China.