Don’t Let the Cameras Turn Away

This time, networks need to stay with the story of mass shootings.

This week, for the first time in my career, I found out about a mass shooting in America just like most of you: not from a TV producer breaking into my earpiece on live TV, or a CNN internal email alert, or from someone shouting in the newsroom, but from a friend.

And I’m processing it with something new: a feeling of deep cynicism. Before, when I was in it, I believed something would change. At CNN, where I worked until 2021, we hosted town halls. I brought together survivors of Parkland with survivors of Columbine, to reflect on two school shootings that occurred two decades apart. I looked these survivors in the eye and believed, along with them, that change was going to come.

Now I know how unsure that change is. That’s partly because of political inaction; Washington hasn’t changed gun laws much. But it’s also because of media coverage.

A day after the shooting in Parkland, Florida, I was standing outside the school next to Representative Ted Deutch, listening to the wails of a mother who had just lost her teenage daughter. Her screams pierced my heart. I stood under the hot camera lights and Florida sun, stuttering, trying to fill the silence, until I allowed my tears to fall on live TV.

The next day, one of my producers interrupted our broadcast from Florida and spoke into my earpiece. News was breaking about President Donald Trump and the FBI. My producer assured me that we’d return to coverage in Parkland, but that right then—I’ll never forget it—“we have to break away to go live to Washington.” But. But. But. Fourteen students were dead. I stood there dumbfounded. A teacher from the school was just out of camera range, waiting to join me for a five-minute live interview. I used the pause in coverage to tell her what was happening and told her that we’d get to her, that her story mattered. But I already knew then that they weren’t coming back to us.

Outside of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, I waited to reappear on my own show, furiously emailing my producers back at CNN headquarters to fight for more airtime on what was happening at Parkland: Come back to me. The teacher! Soon after, I got my marching orders: Come back to New York. I knew what that meant. We were done.

In 2006 I covered my first mass shooting, at an Amish schoolhouse in rural Pennsylvania. Then Virginia Tech. Tucson. Aurora. Newtown. Fort Hood. Isla Vista. Waco. Charleston. Chattanooga. Lafayette. Moneta. Roseburg. Colorado Springs. San Bernardino. Orlando. Dallas. Baton Rouge. Fort Lauderdale. Alexandria. San Francisco. New York City. Little Rock. Antioch. Las Vegas. Sutherland Springs. Parkland. San Bruno. Nashville. Annapolis. Pittsburgh. Thousand Oaks. Poway. Gilroy. El Paso. Dayton. Midland-Odessa. And those are just the ones that immediately come to mind.

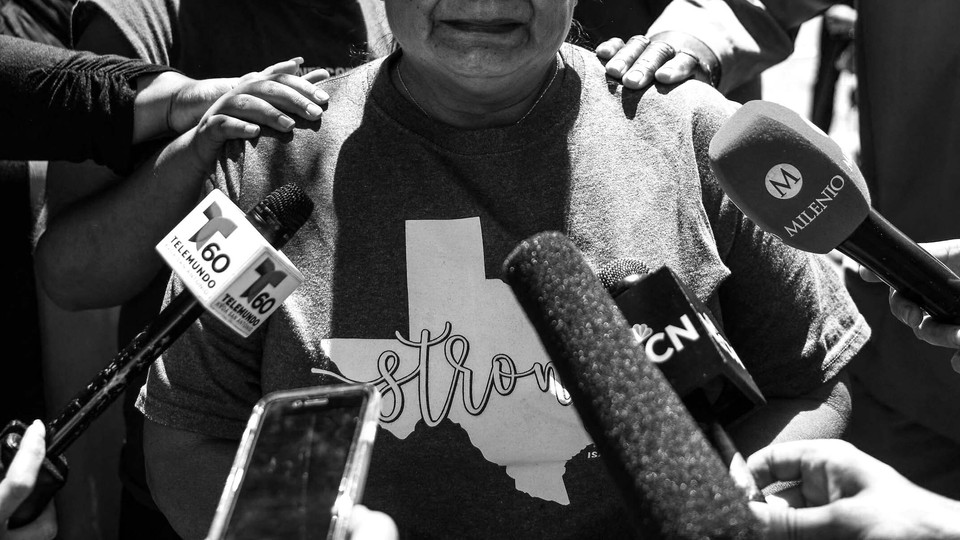

I see it differently this time, removed from the race to rush to Texas and the pressure to land interviews with victims’ families surrounded by the makeshift vigils of flickering candles, teddy bears, and crime tape. Let me tell you what will happen: The news media will be in Texas through this weekend, and then news executives will start paring down the coverage next week. The conversation has already turned to politics, as some pundits urge a focus on mental health and others on guns. Some journalists will try to hold our elected representatives’ feet to the fire. A segment or two will go viral. Americans will share their outrage on social media. And then another story will break next week, and the news cycle will move on.

After a week or 10 days, the outraged public grows tired of hearing about the carnage, loss, and inaction. The audience starts to drop off. The ratings dip. And networks worry about their bottom line. And while the journalists in the field have compassion for the victims of these tragic stories, their bosses at the networks treat the news as ratings-generating revenue sources. No ratings? Less coverage. It’s as simple as that.

Having been part of the cable-news machine for more than a decade, I have a few ideas about how it can be fixed. Some of the children at Robb Elementary needed to be identified by DNA because their bodies had been ripped apart by assault-style weapons. I remember standing in silence as I watched one tiny white casket wheeled out of a funeral home when I was covering Sandy Hook in 2012. I had the thought then: Would minds change about guns in America if we got permission to show what was left of the children before they were placed in the caskets? Would a grieving parent ever agree to do this? I figured this would never happen. But perhaps now is finally the time to ask.

Television networks regularly assign correspondents to beats—specific topics such as the White House, crime and justice, or the State Department—where journalists can take time to specialize, dig deep, and doggedly chase tips. How about adding mass shootings as a regular beat? Reporters should pound on the doors of senators who continue to vote no on gun-control legislation, who are prepared to sacrifice lives on the altar of the NRA and the good ol’ boys.

And news executives should spend what it takes to stay a little longer in these communities. Respect the wishes of the victims’ families, but tell that story in every show so that the audience can’t look away. I know that keeping crews in the field is expensive, but 19 children and two teachers? There is no higher cost than that.