[Note: he/him pronouns are used to refer to Remy Boydell throughout this review at the artist's request]

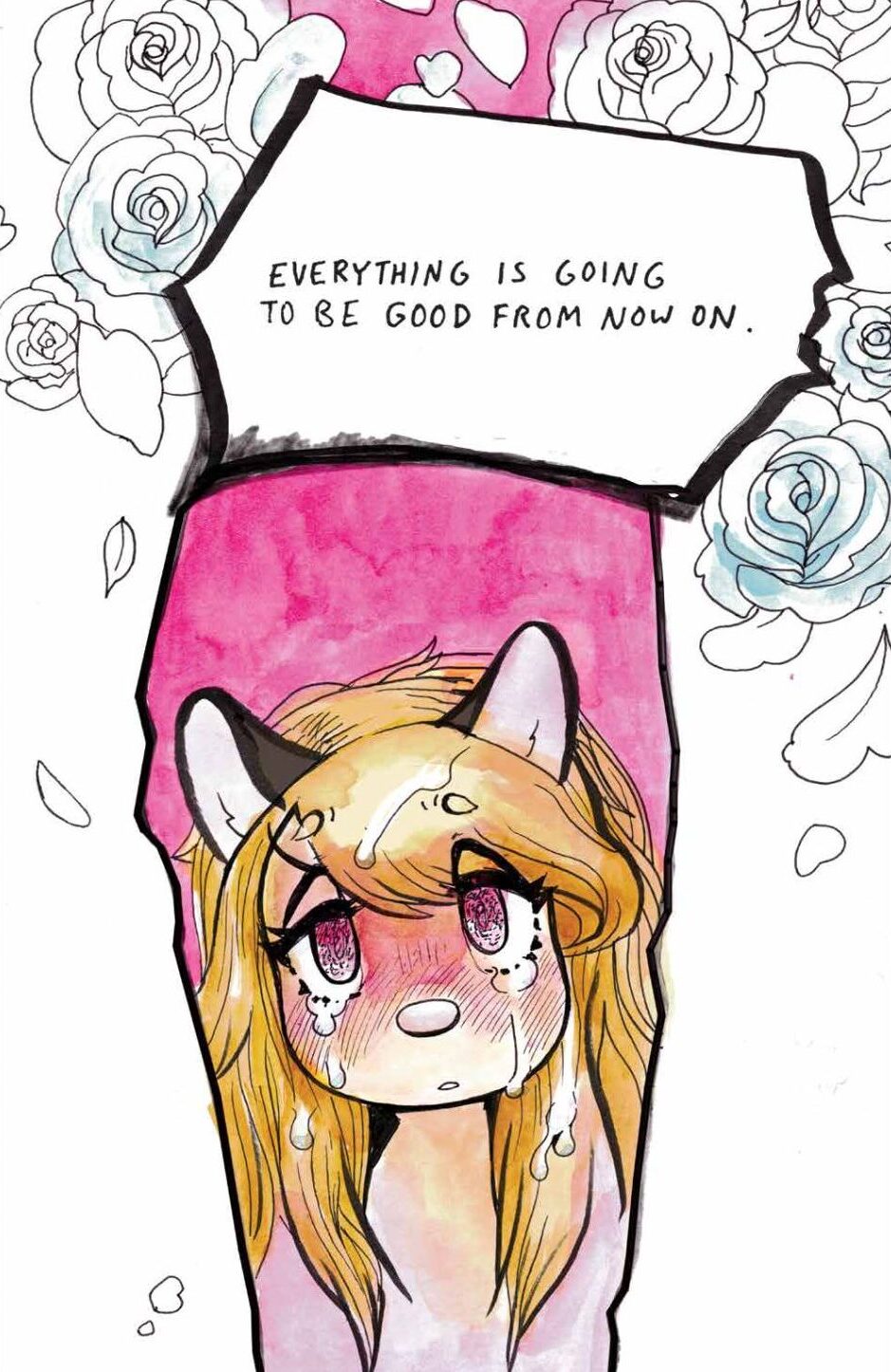

“’Failure to thrive after trauma’ and ‘the end of the world’ are both stages I genuinely believe you can pass through,” writes Remy Boydell in a brief afterward to his new graphic novel 920London. The comic is preoccupied with the passage through the emotional states suggested by this coda; not a beginning, end or dramatic progression but a time spent dwelling inside this hopeless feeling. Set amidst a backdrop of the 2000s pop punk scene, the comic is a natural progression of Boydell’s use of furry style to tell marginalized queer stories – like furry, emo is a cultural aesthetic whose codification as cringe intertwines with homophobia and the misogynistic dismissals of marginal, traumatized experiences as vapid, uncool. Like the trans sex worker protagonist of his previous graphic novel The Pervert (co-written by Michelle Perez) Boydell’s focus is on a hopeless journey with a hopeful destination that isn’t quite reached but might well soon be, moving forward but stagnant, something just out of reach.

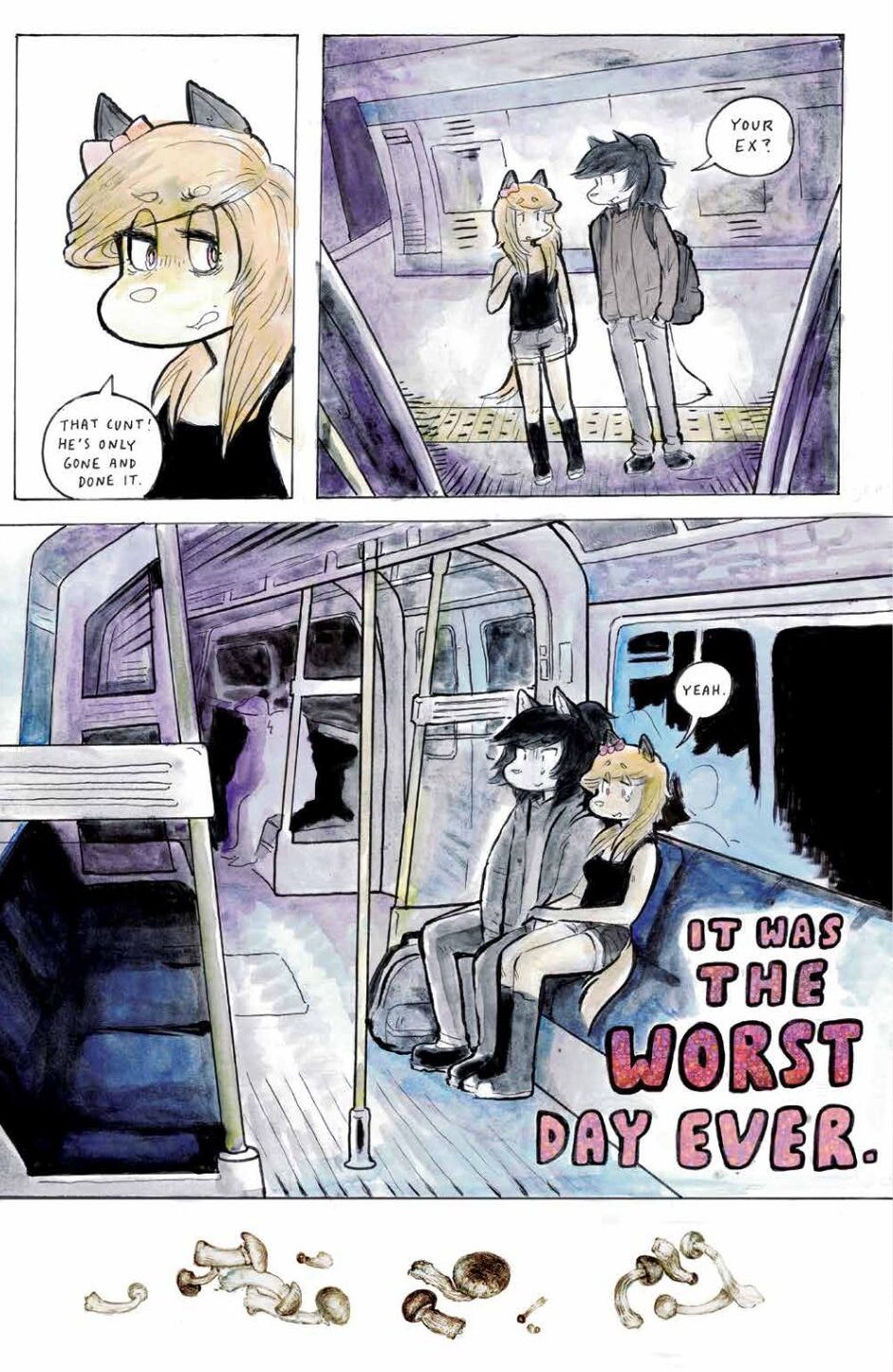

920London follows a codependent relationship of two despairing UK scene kids, the wonderfully named Kiki Curbstomp and Hana Venom. Both are at low points in their lives, in a state that one can’t quite be sure should be called gradual recovery or downward spiral. What “happened” to Kiki is clear enough – she is traumatized from an abusive relationship with Jake Price, a pop punk crooner with a suspicious resemblance to Garfield, whose face is inescapably plastered across billboards, subways, magazine covers. Hana’s past suffering is ambiguous, but her pain is clear – she struggles intensely with gender dysphoria, and in one of the book’s most upsetting passages she confesses to the reader in narration that she has “to imagine awful stuff happening to me so I can get off.” The comic is an exploration of these two young women and their pain, not as a voyeuristic gaze into the violence that has clearly shaped them but the lives they now inhabit in its wake.

Boydell’s stories follow short mundane episodes these characters’ daily life together, the sort of little narrative vignettes that manga readers would call “slice-of-life” episodes, rendered in beautiful, light watercolors with a pale warmth that itself is reminiscent of the dysphoric, dissociative fog that rests over life in the wake of intense panic. Over the course of the book we follow Hana’s repeated attempts to homegrow magic mushrooms after the drug has been made illegal, follow the couple on outings to night clubs and house parties, on days and nights staid in, in and out of public transit, in and out of arguments, breakdowns, reverie. While it is hard to tell (for them as much as for the reader) if their relationship is still romantic, it is clearly intimate: difficult, often hurtful but not exactly “toxic”.

The codependency Kiki and Hana share is a sort of mutually assured ideation – both of them feel that they are missing or have lost something, but what they have lost, what they now have, and what they want, is different. Kiki is more comfortable with presenting in feminine-coded ways than Hana, who hides her transfemme figure under baggy hoodies most days – Boydell admirably never specifies this explicitly but I gathered from how she and Hana interact with each other that Kiki may be cisgendered, or at the very least much more comfortable with her binary gender identity than Hana. Kiki does not worry about how her gender presentation might effect how people see her with the same oppressive intensity that Hana carries with herself as a gender-nonconforming femme under the judgmental watch of transmisogynist society. However, Kiki’s gender presentation is also infantilizing. Hana’s suicidal ideation is quiet and internal (or rather, private and self-inflicted), which can sometimes look like maturity. Kiki acts out self-destructively with risky behavior in public, which can look like confidence. Kiki has a simple narrative for her trauma that she eagerly describes despite the pain it clearly causes her to do so; Hana serves as narrator for most of the stories in the comic, but we hear very little about her past.

There’s a way that these two women can see the strength and energy they feel missing in themselves in the other, comforting to see reflections of one’s own traumas and dreams in another. But for Kiki and Hana the pain lies in what the other girl can never be – loving someone can be experienced as a sort of self-liberation through projection, identifying with someone else’s experiences, but what do you do when someone you love can’t save herself? How do you love someone and find your future if the person you love is also grasping for a future that might look different than the future you want for yourself? This interpersonal despair recalls at times similar dynamics explored in Inio Asano’s Goodnight Punpun and A Girl on the Shore (Asano is a stated influence on Boydell’s work; Boydell interviewed him for Paste in 2018, and there is something about the way Boydell draws hair and utilizes photo reference in this book that reminds me of Asano’s gentle yet starkly precise line and approach to compositions), but Asano often veers into solipsistic fatality in the service of drama that Boydell never approaches while plumbing psychological depths that are as deep and murky. Perhaps as a result he is more successful (to my mind) at achieving a heartfelt and profoundly confessional compassion for people in despair that isn’t easily conflated with the nihilistic manifesto of an incel or the misplaced pity of a liberal voyeur.

In describing 920London, I find myself running into a real problem as a critic. The problem is one of the nature of description itself. The experiences depicted in 920London are recognizable to me as a trans woman who has lived through traumatic experiences and as someone who relates to queer, traumatized, and disabled people. However, Boydell’s work does not preoccupy itself with explaining those experiences or feeding them into a conventionally moralizing (and thus critically explicable) narrative. In describing Boydell’s characters, I have diagnosed them. I have passed judgement on them, and the language available to me to describe their experiences is frankly much more judgmental than any that came to mind while I was reading the work. Even to talk about what I am struggling against creates a problematic binary – to speak against clinicality is, for the neurotypical audience, to suggest anti-psychology; to speak against morality is to suggest a preference for amorality, which in heteronormative parlance is equated with evil. There are experiences, scary ones, wonderful ones, just outside the scope of the comics pages that I can infer but what good would it do to if I identify these, especially for the cis male baby boomers and gen x readers of the website? I could be wrong. And yet these lives are so painfully vivid to me.

Maybe the best way to talk about 920London is by the “slice of life” descriptor I used earlier. These comics are about two cute girls going about their day. How different is that from a four panel gag comic? How different is that from a series of vignettes about school festivals and going to the beach? The difference is whose lives are being sliced. For better or for worse, trauma is currently best understood by audiences and critics today as narratives, narratives that have climaxes and resolutions, inciting incidents and a moment at which the former victim overcomes and becomes an empowered survivor. The voyeuristic gaze of the sympathetic narrative pities us and then insists we get back on our feet like the triumphant final girl in a conventional slasher movie. But for Hana and Kiki, the incidents that they surely lived through before the beginning of the book might not have hurt so much as the memories and echoes they carry with them in the present. A future that is brighter is both possible and something to hope for but it isn’t something that will fix them, nor is it something that will prevent their most painful, stuck years from having joyful moments, fun moments, from being normal. And it wouldn’t be all that strange to look back on memories like the ones depicted in these stories with warmth and nostalgia. The stories in 920London aren’t about hopelessness but about how richly meaningful those dreadful empty years in transit can be. It’s art like this that can give all of us hope, and, for some of us at least, a comforting place to dwell.