In her teens, Leticia Sierra realized that the future she had envisioned was out of reach. Sierra, who lived in San Diego, fled her native Mexico after suffering multiple episodes of sexual abuse before her kindergarten year. But since Sierra was an undocumented immigrant, she was not eligible for military service, which she’d need to afford nursing school. “I was blocked from pursuing my dreams,” she says. Two decades later, Sierra’s future was inverted once again. After being pulled over because her then-boyfriend was on the phone while driving—and after being searched without a warrant—the police found several tablets of Vicodin in Sierra’s purse (a friend had given them to her for back pain). Within hours, Sierra was turned over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and deported to Tijuana.

Desperate “to come home and be with my [two-year-old] son again,” Sierra found her way back to San Diego. There, she—like many undocumented immigrants—lived a quiet life one block off Main Street, cleaning homes with her mother and paying her taxes for over a decade.

Things changed again on January 16 of last year. That morning, after dropping her son off at the bus stop, Sierra found a dozen ICE officers waiting outside her home: undercover cruisers still running, arrest warrant in hand. After she changed out of her pajamas, family watching, the officers cuffed her on the hood of one of the SUVs.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

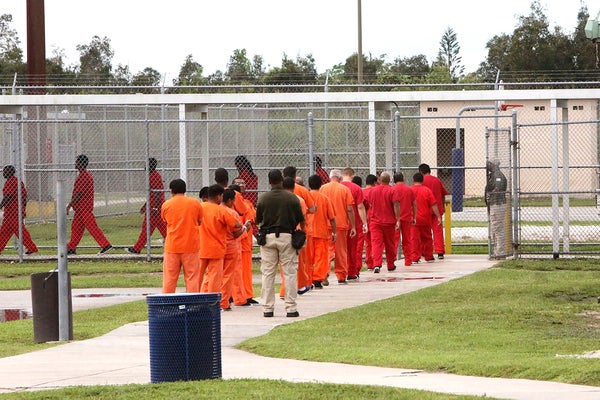

Before she knew it, Sierra had been deposited at ICE’s Otay Mesa detention center to await her immigration proceedings. And there she was, waiting, when COVID-19 hit.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, detention centers have ranked amongst the most dangerous settings in which to live and work. Since March, 2020. ICE facilities have experienced some of the worst outbreaks of the virus: as of February 24 of this year, some 9,569 detainees in total had tested positive for COVID-19. About 10 percent of those tested have had the virus, a figure which was 17 percent higher than the general U.S. population. In the time since ICE began testing its detainees, a detainee has died of the virus nearly every month.

This amount of suffering did not have to happen; these statistics, as they stand today, were not an inevitability. Rather, since March, at the federal level ICE has enacted policies inconsistent with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines, while conducting arrests and raids that run afoul of public health recommendations. And, at the facility level, ICE subcontractors have treated detainees with cruelty and callous disregard—while simultaneously evading local health departments’ recommendations and offers for help.

The first step ICE could have taken was to release detainees—especially those with medical conditions making them vulnerable to the virus. Indeed, early modeling studies predicted that—even amongst the most optimistic assumptions—without “widespread release” of those under custody, detention centers would be a set up for disaster. However, as of late February, ICE had released only about 3,500 detainees vulnerable to the virus. Meanwhile, tens of thousands remain in government custody.

Moreover, despite ICE policies early in the pandemic claiming to delay enforcement actions other than those deemed “mission-critical,” raids on communities across the U.S. continued throughout the spring and summer. Since September, ICE has all but resumed normal operations in neighborhoods across the U.S., tearing people like Sierra away from their families and throwing them behind bars. Including, in sanctuary cities where such federal enforcement actions face restrictions on cooperation by local authorities.

In lieu of reducing detainee populations, ICE (and its subcontracted operators) could have constructed physical safeguards and instituted hygienic protocols within facilities to reduce the spread of the virus. Much as inherent challenges to containment of infectious diseases exist in crowded detention centers—as they do in other carceral settings (like jails and prisons) and congregant facilities (like nursing homes and rehabilitation centers)—theoretically, these settings are amongst the most amenable to strict precautionary procedures.

Yet, clear inaction by ICE and its (for-profit) subcontractors has allowed the virus to run rampant. Since the outset, physicians have noted inconsistencies in ICE infection management policies that “significantly differ” from those set forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). These include policies for intake monitoring, grouped quarantine, and social distancing that failed to meet CDC guidance. The result: “plac[ing] further stress on a system teetering on the verge of disaster” and putting detainee lives at risk, these authors write.

What actions authorities have taken, instead, have been perilous, punitive, and inhumane. They’ve withheld protective equipment; transferred detainees needlessly between facilities; ignored detainees’ medical needs; and physically and mentally abused detainees with fists, pepper spray, and solitary confinement for seeking medical care.

At Otay Mesa, Sierra endured these decisions firsthand.

After an officer contracted COVID-19 in March, staff began wearing protective equipment. But detainees didn’t receive masks for weeks, and those who ripped sleeves off T-shirts as stand-ins for the real thing were put in solitary for “vandalism.”

In April, in order to receive masks, detainees were required to sign a “waiver saying it wasn’t our fault if we got sick,” Sierra said, while they were verbally accosted with ethnic slurs. Officers denied to translate the form for the majority of detainees that didn’t speak English—yet, those who translated it for peers were pepper sprayed and put in solitary for “disturbing the peace.”

By May, detainees were “getting sick left and right”—Sierra herself developed a fever, headache, severe fatigue, and blisters on her mouth and legs—but were denied tests since they “did not meet criteria” for COVID-19, Sierra said. Detainees with psychiatric symptoms—including a peer who seemed to be hallucinating—were put in four-point restraints. Others were vomiting and having diarrhea in bathroom stalls that were shared amongst some 100 bunkmates. The toilets frequently clogged and overflowed, potentially infectious excrement flooding the bathroom floor.

On May 6, Carlos Ernesto Escobar Mejia, a detainee living in the dorm next to Sierra, died of COVID-19.

“They treated us like less than animals,” Sierra said, “every night, I worried that I wouldn’t wake up.”

As all of this was happening, e-mails obtained by Immigrant Defense Advocates and the American Friends Service Committee indicate that officials on the other side of the bars were rejecting, ignoring and avoiding San Diego Public Health Services’ (SDPHS) recommendations.

Internal guidelines addressing PPE use established on April 1 did not require masks for staff or detainees in most circumstances, allowing officer discretion based on their “scope of duties” and “as feasible.” (These guidelines were out of compliance with CDC recommendations; it is unclear whether they were ever updated.) On April 29, SDPHS’ offers for “anything we can do to help mitigate spread” were ignored.

On May 19, SDPHS’ guidance “strongly urging” facilities to test staff were rebuffed; “just so we’re clear—at this point, we have no intention to mass test our staff,” assistant warden Joseph Roemmich replied. On May 29, SDPHS’ revised guidelines to test all asymptomatic staff and inmates were ignored. On July 2, its offers to provide PPE were rejected.

It took until September 21 for the facility to discuss its “COVID containment plan” with SDPHS. It took until September 23 for the facility to collaborate with SDPHS on testing.

Throughout those months, as Roemmich sent regular updates racking up the case numbers (“+1 staff,” he’d write), SDPHS was forced to circle back to resolve errors, inconsistencies and unreported cases. And, all the while, Otay Mesa was releasing potentially infected detainees into San Diego; no list of “street releases” was provided to SDPHS until September 23.

ICE could not be reached for comment on any of the allegations in this article.

Decisions like this—at Otay Mesa and many other facilities—do not only put the health of staff and detainees like Sierra and Mejia in danger. Experts say that since detained individuals and staff exposed to the virus act as “disease vectors” outside the facility, outbreaks in detention centers can be “catastrophic” for neighboring communities by rapidly overwhelming ICU capacity. California State Senator Scott Wiener has labeled ICE a “known super-spreader” of COVID-19.

On July 17, Sierra was released. While she’s left Otay Mesa, it hasn’t left her—she continues to have flashbacks, nightmares, and insomnia. And she hasn’t left the immigration system, either: she’s in asylum proceedings, and her court date got pushed back from November 4 to April 24 of this year. Her son “is afraid whenever I leave the house that I won’t come back,” she said, “if I had to go back, I don’t think I’d make it out.”

As a new administration has entered the White House pledging to “battle for the soul of America,” taking care of people like Sierra is not merely a moral obligation. Ensuring the transparency and accountability of the immigration system that defines this country—in a way that protects the health and humanity of immigrants—is essential to the battle for American lives, too.

This is an opinion and analysis article.