Blaming the victims wrong approach to immigrant children

Vicious rumors are circulating about the large number of unaccompanied children arriving on our borders. Accusations of disease, criminality and fraud are totally unfounded. They blame the victims for creating a humanitarian crisis, and they offer a sad commentary on our willingness to exploit children for short-term political gain.

In response to a proposed shelter for some of these children in Escondido, residents and activists alleged that they would spread tuberculosis and a host of other diseases. Local Rep. Duncan Hunter stoked these fears in a letter to the mayor.

There’s not a shred of evidence of any kind of widespread infection with any communicable disease among the children in U.S. custody. Neither the Centers for Disease Control nor the Department of Health and Human Services has received any credible information of such a threat. Reports from facilities across the country include nothing more severe than a few cases of chickenpox, and an isolated case of the flu.

Disease has been the pretext for a rogue’s gallery of discriminatory policies, from Chinese exclusion and Jim Crow segregation, to kerosene baths on the border and the rejection of Jews fleeing fascism. In each case, disease was simply a metaphor for perceived racial contagion.

This history begs us to stop and think before we view children in need first and foremost as threats, or accept the wildest assumptions about them.

The most inaccurate assumption out there is that these children are “seasoned criminals.” Ironically, this claim comes directly from children’s testimony that they have been the victims of organized crime, street gangs, and domestic violence.

Some cable news commentators, congressmen, and others allege that these claims are part of a “well-rehearsed” scheme for “gaming” the system. But, rather than Manchurian candidates rattling off a rote story, these children have described a diverse range of violence, in great detail.

A 2014 study by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) found that 58 percent of these children are likely eligible for international protection. The study involved 400 in-depth interviews by teams of experienced researchers. In a similar study in 2006, the commission found that only 13 percent were likely eligible for international protection.

Throughout the current drug war with its beheadings and mass graves, murder rates in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have been higher than in Mexico. Many of the forms of violence in contemporary Central America target children in particular — forced recruitment into gangs, lethal attacks on public buses, kidnapping for ransom, and sex trafficking.

Many unaccompanied children have heard rumors that if they make it to the United States, they will not be deported, and they will be able to reunite with their families. This explains why most surrender to U.S. law enforcement once they reach the border.

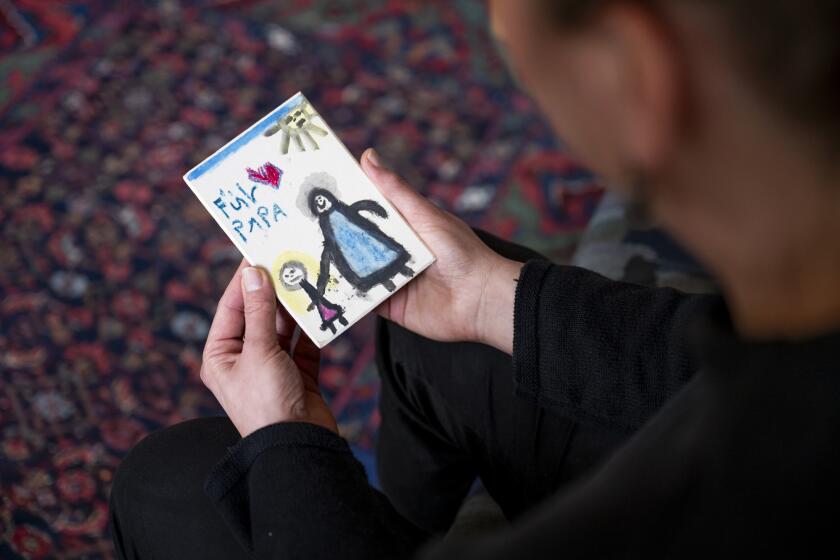

However, these children are often traumatized after a perilous journey through Mexico. In interrogations with immigration officials, interviews with journalists or initial screenings with attorneys, unaccompanied children are often hesitant to reveal their full histories, and eager to tell adult authority figures a simple, plausible story — the truth, just not the whole truth.

Moreover, the fact that they have some hope of safety and a decent future in the United States does not explain why they leave their home communities.

If they were coming primarily due to the perceived laxity of U.S. immigration enforcement or a misperception that they were going to receive some kind of status here, then why aren’t large numbers of children coming from other countries in the region?

Nicaragua is poorer, sends more migrants abroad, and is just as economically dependent upon the remittances they send home as El Salvador, Honduras, or Guatemala. And yet there’s no mass exodus of Nicaraguan children to the United States.

The large-scale displacement of Central American children doesn’t have a singular cause, easily reducible to a sound bite. Some of it is rooted in unreconciled legacies of civil war and dictatorship, some of it in the drug war, and some of it in patterns of poverty and inequality going back more than a century.

It’s clear that U.S. immigration policy is neither the sole cause nor the sole solution. The same goes for beefing up regional borders and empowering foreign security forces with miserable human rights records. These measures will neither protect children from harm, nor will they address the underlying causes of the current crisis.

The question is whether we’ll continue to use children as fuel for ideological debates and an immigration policy that swings wildly between aggressive enforcement and ad hoc relief.

We have an opportunity to pursue a different path and it must begin by treating these children first and foremost as children, assessing their individual claims on their merits, and placing them wherever their best interests dictate.

Meanwhile, the world is watching us pack kids into overcrowded Border Patrol stations, like so many sardines in space blankets.

Get Weekend Opinion on Sundays and Reader Opinion on Mondays

Editorials, commentary and more delivered Sunday morning, and Reader Reaction on Mondays.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.