Lawsuit asks federal judge to order reforms across San Diego County jails

U.S. District Court complaint, which seeks class action status, is the second demand for outside intervention in as many weeks

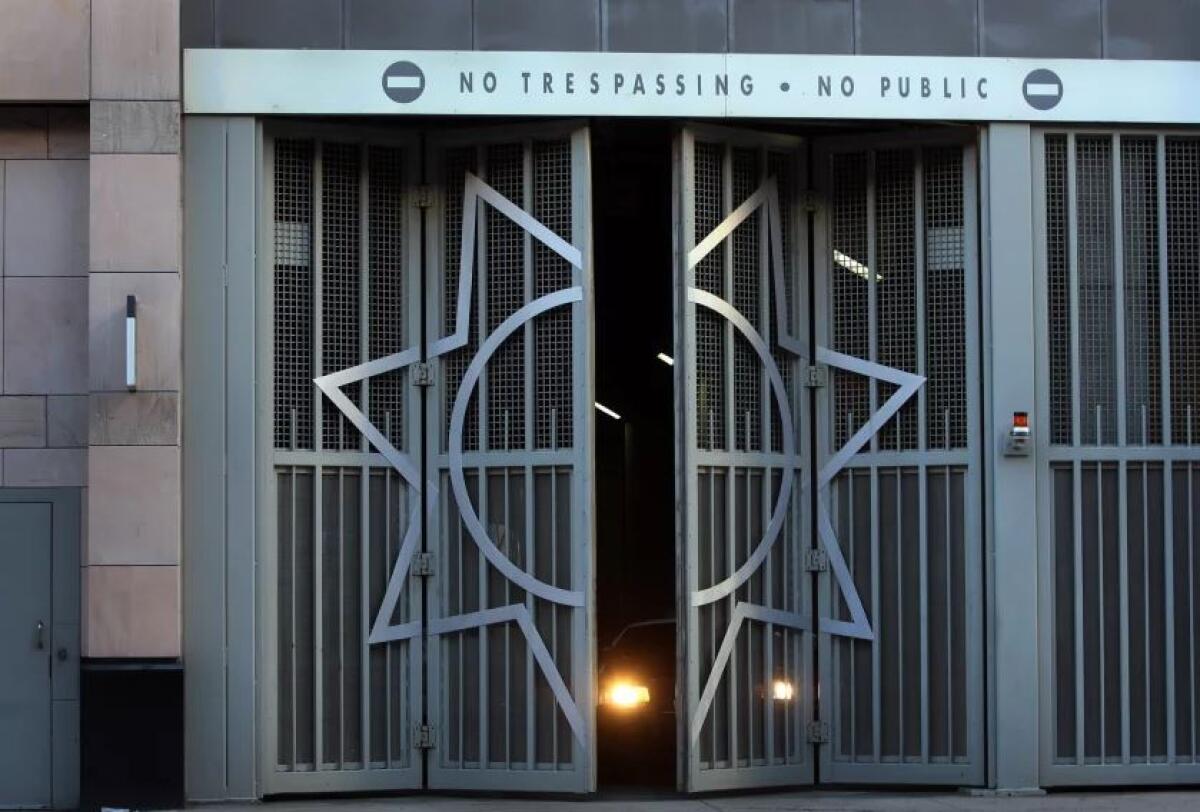

Days after a state audit said conditions in San Diego County jails are so unsafe that legislation is needed to impose reforms, the Sheriff’s Department is facing new allegations of deficiencies and mismanagement within its jails.

In a lawsuit filed late Wednesday, a team of civil rights attorneys is asking a federal judge to force Acting Sheriff Kelly Martinez to implement a host of new practices aimed at preventing in-custody deaths and improving care for mentally ill and physically disabled inmates.

The 200-plus-page complaint was filed in U.S. District Court in San Diego less than a week after longtime Sheriff Bill Gore left his post for early retirement.

Among other requests, the lawsuit asks a judge to order the Sheriff’s Department to improve medical practices by providing appropriate staffing levels, improved training, and outside care when needed and to make sure deputies do not interfere with healthcare decisions.

The report issued last week by the California State Auditor included many of the same recommendations.

In addition to the Sheriff’s Department, the case names San Diego County, a local hospital district, three healthcare contractors and a physician as defendants.

Both the County of San Diego and the Sheriff’s Department declined to comment on the lawsuit, citing pending litigation.

Co-defendants Correctional Healthcare Partners Inc., Tri-City Medical Center, Liberty Healthcare Inc., Mid-America Health Inc. and Dr. Logan Haak did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys said Gore was told before leaving office about the accusations of neglect and misconduct in the lawsuit.

“San Diego County residents are unnecessarily suffering and dying in the county’s jail facilities due to extraordinarily dangerous and deadly conditions, policies and practices that have been allowed to persist for many years,” the complaint states. “The crisis at the jail is not a new development.”

The plaintiffs are not seeking money. Instead, they want a federal judge to order the Sheriff’s Department to upgrade its medical care, mental health treatment and other services that are required to be provided by the government whenever people are taken into custody.

“We hope it forces the Sheriff’s Department to take basic, common-sense, measures to keep people safe,” said Jonathan Markovitz, a staff attorney with the ACLU of San Diego and Imperial Counties and one of 10 lawyers from four different law firms to file the complaint.

“We hope it drives home the need to divert people from the jail system and create community-based options for care and rehabilitation,” he said.

In addition to the local ACLU chapter, the class-action complaint was filed by attorneys from DLA Piper; Rosen, Bien, Galvan & Grunfeld; and lawyer Aaron J. Fischer, who co-wrote a Disability Rights California report on San Diego County jails in 2018.

Fischer has investigated and sued jails across the state. He said the local facilities are among the worst he has seen.

“What is striking is that San Diego County’s jails stand on their own in the level of mistreatment of people and the sheer awfulness of the conditions,” he said. “It’s a system that has been resistant to necessary and urgent changes, even as other jurisdictions recognize the need and have begun to act.”

The seven named plaintiffs all spent time in San Diego County custody and all have been diagnosed with a serious mental illness or debilitating physical conditions, the lawsuit states.

Darryl Dunsmore, for example, suffers from ankylosing spondylitis, a form of early onset arthritis that sometimes leaves him in a state of paralysis. He relies on a wheelchair to move around and required a modified spoon to eat, yet deputies confiscated both items “because they decided he did not need them,” the complaint says.

In response, Dunsmore became distraught. He was stripped of his clothing and placed in an isolation cell where he was unable to get to the toilet, the complaint says, and was forced to urinate and defecate on the cell floor. Without his modified spoon, his only option was to eat with his hands.

“He often made a mess in the cell and was forced to sleep among his own feces and other trash,” the complaint says.

Plaintiff Laura Zoerner, who suffers from mental illness and addiction, was also placed in isolation after complaining about lapses in care; in Zoerner’s case, it was “excruciating” tooth pain that eventually required oral surgery.

When Zoerner returned to the jail after surgery, the complaint says, the medical staff stopped giving her medication to treat her bi-polar disorder. Zoerner told attorneys that her requests to restart her medication went ignored, so she resorted to banging her head against the cell door until it bled.

The lawsuit said there is a dire shortage of clinical staff in the jails, which Gore has described as the largest mental health facilities in the county. As of this month, the complaint says, almost 1,000 inmates in the two largest jails are waiting to see a clinician.

The waiting list at Central Jail has grown to 300 people — one-third of the inmate population. The backlog at the George Bailey Detention Facility exceeds 500 people — also more than a third of its population.

Both the state audit and the class-action lawsuit claim delays in psychiatric care and a lack of proper mental health screenings during booking have led to an excessive number of suicides and suicide attempts.

There also is no space for confidential therapy sessions. The lawsuit said cell-side therapy sessions — where deputies and other inmates can listen in — can exacerbate cases of mental illness.

The lawsuit is not the first time the lack of mental health treatment space has been singled out.

In 2018, an investigation by the advocacy group Disability Rights California found that cell-side assessments “undermine treatment, as prisoners are reluctant to disclose sensitive information about their mental health history or current situation.”

The same year, the Sheriff’s Department hired an expert in jail suicides to conduct an independent assessment of the sheriff’s suicide prevention policies. Among the findings cited by consultant Lindsay Hayes was a lack of “sound” confidentiality that would allow a patient to privately discuss medical and mental health concerns.

The lack of proper medical and mental health care is compounded by unsanitary living conditions that have led to illness and infection, the lawsuit asserts.

People suffering from incontinence, for example, are often forced to reuse dirty catheters and are denied showers and clean clothing if they urinate or defecate on themselves, the suit says.

The legal complaint includes photos of feces-covered walls in a cell intended for suicidal inmates and black mold caking a ceiling tile. It also depicts a dead rat in a medical examination room in the Vista jail and heaps of trash and human waste in the Central Jail unit reserved for psychiatric patients.

Last year, the filth and grime led to an outbreak of bacterial infections, the complaint says. One man had to go to the hospital to have infected tissue removed. When he returned, he was put in a cell infested with flies and ants, the complaint says.

His wound became re-infected and he was forced to return to the hospital.

Both the lawsuit and state audit follow years of reporting by The San Diego Union-Tribune on deaths in San Diego County jails, including a six-month investigation called “Dying Behind Bars” published in 2019.

Multiple independent studies have found that the San Diego County jail system has a significantly higher mortality rate than other large California counties, including Los Angeles, whose jails are currently under court-ordered monitoring.

Since 2009, lapses in inmate healthcare have cost millions of dollars in court fees, legal settlements and jury awards — money that comes directly from taxpayers because San Diego County is self-insured.

In addition to unsanitary conditions and gaps in medical and mental health treatment, the lawsuit claims that jailers often fail to follow even the minimum standard of care for inmates going through drug and alcohol withdrawal.

The Sheriff’s Department has taken years to implement what’s called medication-assisted treatment, or MAT, which calls for providing one of three federally approved medications to curb drug cravings and withdrawal symptoms. The lawsuit blames a rise in fentanyl overdoses on the lack of MAT.

It also cites the case of Saxon Rodriguez, a young man who struggled with opiate addiction who died from a fentanyl overdose four days after he was booked into jail. Rodriguez’s sister, Sabrina Weddle, told the Union-Tribune in October that her brother might have turned to fentanyl to ease withdrawal symptoms that could have been addressed through medication-assisted treatment.

“Without adequate treatment for substance use disorders, including MAT, incarcerated people are more likely to relapse — a problem exacerbated by the ready availability of fentanyl and other drugs inside the jail,” she said.

The lawsuit also said San Diego County does not do enough to find alternatives to incarceration, practices that would ease overcrowding and unburden medical staff.

The complaint singles out a plan from county Supervisor Terra Lawson-Remer to examine whether people with addiction or mental illness issues could be enrolled in treatment programs instead of locked up and whether low-level offenders could remain at home pending trial.

“Lawson-Remer acknowledged that even a day or two in jail ‘can result in more, not less, future contact with the criminal justice system,’” the suit says.

According to the complaint, the Sheriff’s Department could reduce its jail population by making policy changes to programs like the County Parole and Alternative Custody program, or CPAC, which allows people to remain under home detention, monitored by GPS, while awaiting trial.

But the department requires participants to have a land-line telephone at home, the lawsuit notes, “which disqualifies people who are poor, people who only have cell phones, individuals without stable housing and many others.”

The lawsuit comes amid a nationwide shortage of healthcare workers due to the lingering COVID-19 pandemic. The shortage has made staffing more difficult at hospitals and healthcare centers everywhere, and especially difficult in correctional settings.

The class-action case has yet to be scheduled for a hearing.

Earlier this year, the San Diego ACLU asked a judge to grant an immediate injunction to force the sheriff to follow federal public health guidelines to prevent the spread of the virus. A ruling on that motion has not yet been issued.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.