The Color of Authority: San Diego police, sheriff’s deputies disproportionately target minorities, data show

Blacks, Latinos, Native Americans bear brunt of racial biases in local policing

Long before protests erupted across San Diego County over the death of George Floyd, a Black man who died last May after a Minneapolis police officer kneeled on his neck for almost nine minutes, community leaders have called on local law enforcement officials to address persistent racial disparities in policing.

For years, study after study has shown that people of color — especially Blacks — are stopped, searched and arrested at higher rates than their White counterparts.

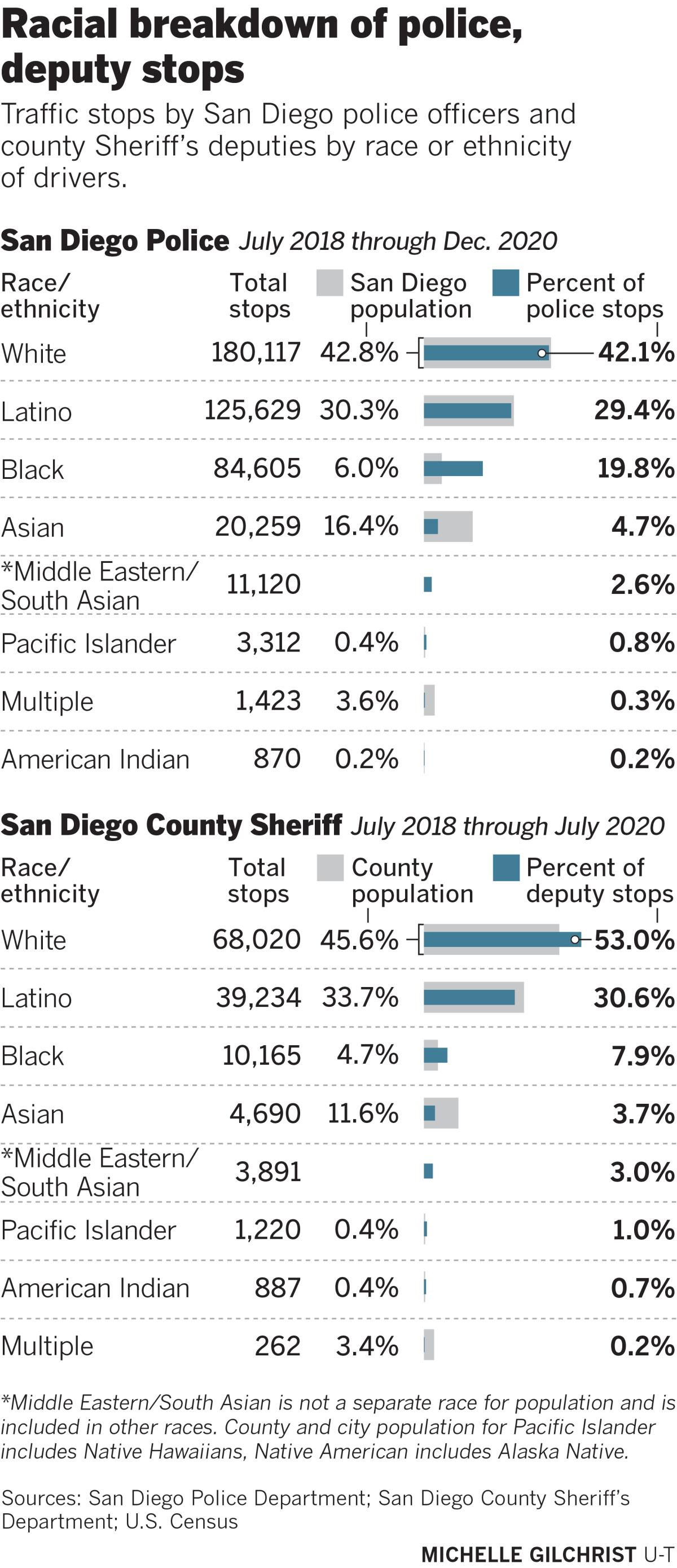

A new analysis by The San Diego Union-Tribune of nearly 500,000 stops of drivers and pedestrians made by San Diego police and sheriff’s deputies shows that the county’s two largest law enforcement agencies have work to do to earn the trust of minority communities.

Nearly one in five stops initiated by the San Diego Police Department from July 2018 through December 2020 involved Black people, even though they make up less than 6 percent of the city’s population, the analysis showed.

San Diego officers also were more likely to use force on minority groups, including Black and Latino people, than Whites, while sheriff’s deputies were more likely to use force on Native Americans.

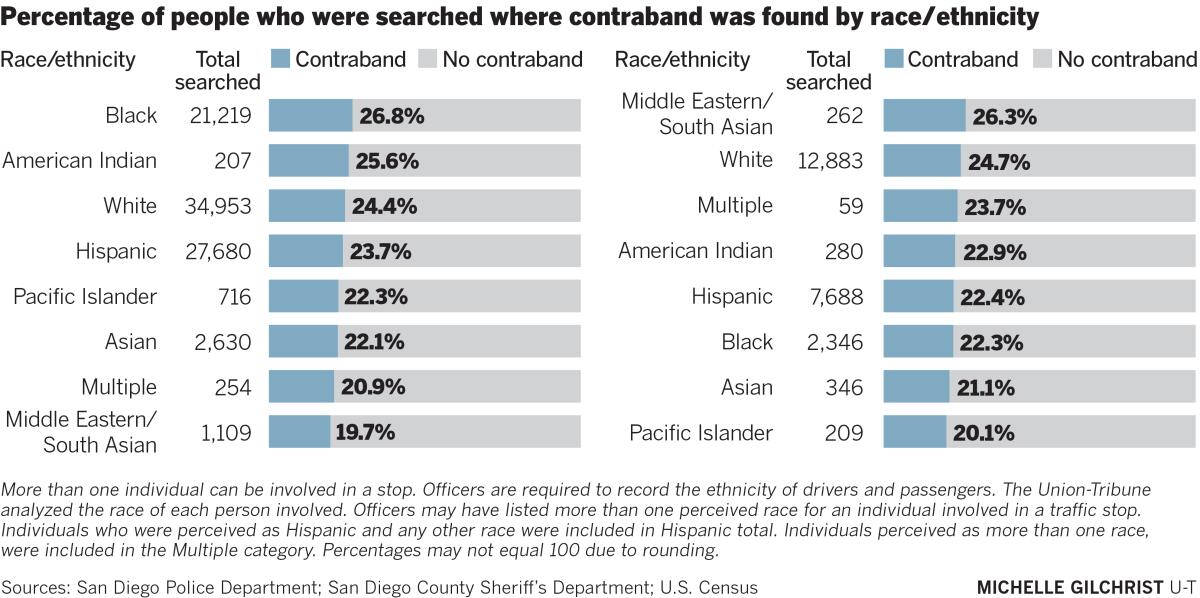

Both departments searched Black and Native American people at higher rates than Whites. According to Sheriff’s Department data, those two minority groups were less likely to be found with contraband than Whites who were searched.

San Diego police also arrested Native Americans, Blacks, Pacific Islanders and Latinos at higher rates than Whites.

The two biggest San Diego County law enforcement agencies are not an anomaly.

Black people across California were stopped at more than twice their share of the population in 2019, according to state data. And Blacks, Latinos and Native Americans all were searched at higher rates despite being found with contraband less often than Whites.

Blacks and Latinos statewide also were more likely to have force used against them than Whites, the data show.

Christie Hill, deputy advocacy director for the American Civil Liberties Union of San Diego and Imperial Counties, said the Union-Tribune’s analysis “affirms what community members have been saying for years about experiencing a different type of policing compared to White people in our region.”

Hill said while studies are helpful, policymakers need to act.

“There’s anger, justified anger, about the lack of action, not only from law enforcement but our elected leaders because there were studies done in the early 2000s that found disparities in how the police were conducting traffic stops,” she said.

Local police departments have implemented some reforms, most notably since the nationwide unrest last spring.

In the immediate aftermath of the Floyd killing, every department in the county banned a controversial neck hold known as the carotid restraint. The tactic aimed at subduing suspects by cutting off the flow of oxygen to their brains was used disproportionately on Black people, the Union-Tribune previously reported.

San Diego police also reconfigured the department’s gang-suppression team, in part to reduce the impact of saturation patrols, which flood certain neighborhoods with officers. Police also adopted new policies setting limits on officers’ actions during protests.

Even so, community leaders say, San Diego County sheriff and police chiefs have shied away from changes that would more directly address racial disparities in law enforcement.

Oversight groups like the city of San Diego’s Community Advisory Board and the American Civil Liberties Union of San Diego and Imperial Counties have urged police agencies to ban consent searches, when officers ask to search someone despite there being no evidence of criminal wrongdoing.

San Diego police officials said their consent search rules are currently under review.

Community groups also want police to suspend pretext stops, when officers use things like minor traffic violations to pull over drivers and search their vehicles. It’s a technique police have defended in the past as an important investigatory tool.

“People have not been marching and turning out to city council meetings to speak for 10 hours because they want you to change one aspect of what you’re doing,” Hill said. “Folks want to see a transformation in how our cities are responding to public safety and redefining what that means.”

For the ACLU and others, that transformation starts with reducing the role of police and investing in community-based solutions.

It also means further diversifying the law enforcement workforce. The San Diego Police Department is 59 percent White; the Sheriff’s department is 54 percent White, records show.

San Diego police Capt. Jeffrey Jordon acknowledged that officer bias contributes, in part, to policing disparities. When explicit bias occurs, he said, the department is committed to taking immediate, corrective action to eliminate that behavior.

Jordon also said factors outside officers’ control are more responsible for racial discrepancies in policing than bias — situations like homelessness, mental illness and criminal activity.

“I would not put officer bias at the top of the list,” he said. “I think there are other risk factors that take place that cause disparate impacts at far greater extents than inter-personal ones.”

Slave patrols

As evidence of disparity persists, some experts argue that minority communities should not have to prove that racial bias is at the root of such discrepancies in the data, particularly when the history of policing is deeply racist.

American policing, after all, originated soon after the revolution, when White Southerners worried about rebellions among their communities of enslaved people.

Plantation owners organized so-called slave patrols to hunt for runaways, deter any effort to revolt and maintain discipline, according to historian Gary Potter of Eastern Kentucky University.

“The history of police work in the South grows out of this early fascination, by White patrollers, with what African American slaves were doing,” Potter wrote. “Most law enforcement was, by definition, White patrolmen watching, catching, or beating Black slaves.”

Jack Glaser, a UC Berkeley professor and expert on racial profiling, said a wave of professionalization swept across American police agencies in the 1970s but likely did not eradicate prejudice in the rank and file.

He said law enforcement officials need to more fully demonstrate they are working to improve.

“The burden of proof shouldn’t be on the people who are arguing that there is racial bias” in policing, Glaser said. “I think at the very least there should be an equal burden of proof and that evidence of disparity should be taken very seriously.”

Using data to expose long-running disparities in law enforcement is fairly straightforward. It is more difficult to determine whether the inequities stem from bias or animus on the part of officers and deputies.

Over the years, researchers have developed tests to help identify when racial bias plays a role in local policing. For example, examining who officers choose to search most often and comparing that data to those most often found with contraband, can indicate biases.

But experts caution that even statistical tests designed to single out prejudice may not prove accurate — even if there is evidence to suggest that bias exists.

The veil of darkness test, for example, is used by criminal justice researchers across the country. It attempts to identify racial profiling by determining whether officers pull over drivers of particular ethnicities more often during daylight hours — when race is presumably more visible — than after dark.

The Union-Tribune’s veil of darkness analysis of San Diego police and sheriff’s data found little evidence of overt racial bias.

For example, Asian drivers were pulled over by sheriff’s deputies from July 2018 through June 2020 slightly more often during the day, the analysis showed. But experts said it was not clear if that was attributable to bias or to some unknown factor.

Street lights, for example, could allow deputies to observe a person’s race at night.

Law enforcement officers also may racially profile in different ways after dark, by making assumptions about a person’s race based on the car they drive, the neighborhood they are in or the time of day the stop occurs. None of these tendencies may be reflected in the data.

Over-policing in communities of color — which often results in a disproportionate amount of police activity — can also mask the veil of darkness findings, said Glaser.

“The absence of a disparity is very weak evidence of an absence of bias, and that’s partly because police can make inferences about the race of drivers in the dark, so the test is not pure in that sense,” he said.

The UC Berkeley professor said the veil of darkness survey is a very smart test that has been carefully developed by smart people.

“It’s useful but, at the end of the day, it’s prone to false negatives,” Glaser said.

Change the disparity

Misleading results are one of many reasons law enforcement officials should pay close attention to statistical disparities in police stops and other activities — regardless of whether evidence of bias is found, researchers say.

Kent Lee is co-chair of the San Diego Asian Pacific Islander Coalition, a group that formed to denounce racist behavior toward Asians and Pacific Islanders during the pandemic.

He said the possibility of bias seen in the Sheriff’s Department’s veil of darkness results weren’t particularly surprising and noted that many communities of color have worked for years to draw attention to the uneven levels of policing in their neighborhoods.

“We know that incidents of bias already exist regularly, and it’s just a matter of whether we see it or not,” Lee said.

Some prejudice was especially evident during the pandemic, he added.

Long before the state’s stay-at-home order was issued last March, Asian and Pacific Islander-owned businesses saw their revenue dry up as concerns about the coronavirus spread throughout the United States, local business groups said.

Asians and Pacific Islanders also reported being victims of racist and xenophobic acts.

“I think a study like this is important not just for the community to understand, but I think it’s also an opportunity for law enforcement to look within and see what opportunities they have to address bias or disparities,” Lee said. “I think, at the end of the day, we should all see it as beneficial when there’s an opportunity to better practices and improve upon our perceptions.”

Lee said law enforcement leaders have made an effort to reach out to minority communities over the years, both to diversify their own forces and to build stronger relationships. But there is much more work to be done, he said.

A number of organizations and advocacy groups are working to help law enforcement agencies eliminate implicit and overt prejudice in their ranks.

Both the San Diego police and sheriff’s departments have partnered with the Center for Policing Equity, a nonprofit at Yale University that uses data to help police agencies identify and eliminate bias.

Chris Burbank is the center’s vice president of law enforcement strategy and the former chief of police in Salt Lake City, Utah. He would not speakabout specific findings from his organization’s work with the San Diego police and sheriff’s departments but said the center sees many of the same disparities when they partner with departments.

“I think we need to start saying, ‘Here’s the disparity. Now, how do we change that disparity?’” Burbank said.

Reducing bias in law enforcement starts with recognizing the problem and adopting strategies and policies to eliminate it, he said.

“It’s very specific to the direction given to police officers, the way we patrol (and) where we’re doing the enforcement,” Burbank said. “How could departments do nothing about that?”

And that’s just first steps.

When statistics show where and when racial bias is occurring, law enforcement officials and community leaders should chart a path forward together, Burbank said.

Most often that begins with a hard look at the data.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.