Supporters of San Pasqual Academy rally to fight closure

The news last week that San Pasqual Academy would need to close this fall took staff and students by surprise, and by late last week they joined former students and others in a campaign to save the boarding school for foster children.

Citing declining enrollment and recent changes in state and federal law, California regulators notified San Diego County child-welfare officials early this month that they must close the academy by Oct. 1. The Escondido campus was the first-in-the-nation residential home for dependents of the Juvenile Court.

A pilot program that had allowed the 20-year-old institution to operate was slated to expire Dec. 31, but state officials told the county earlier this year that the project would be ending even sooner.

In October, the state will begin implementing a federal law that discourages funding for congregate living in foster care facilities. The county will need to find new homes, preferably with families, for the approximately 70 students who live at the academy.

A San Pasqual Academy student identified as Kimberly E. on Monday started a Change.org petition to keep the school open. The petition drive began one day after The San Diego Union-Tribune reported the looming shutdown. In her description, Kimberly said students learned about the closure from the newspaper and presented her best argument against closing the school.

“Yes, it will be easy for the county to put us students into foster homes and family but would that actually be the safest option?” the petition said. “In my opinion, it will not be the safest option due to the fact that a lot of foster homes don’t always feed the kids well, sometimes don’t even buy us clothes.

“Also a lot of foster homes do abuse kids behind doors. Also, putting kids with their family might seem like a good idea but family can also abuse kids,” it said.

By Friday, the petition had more than 4,000 signatures toward its 5,000-signature goal.

One day earlier, the Rev. Shane Harris, a former foster child and San Pasqual Academy student who now runs a civil rights group called the People’s Association of Justice Advocates, sent a letter to Gov. Gavin Newsom asking the state not to close the school before the end of the year.

Harris said moving the end date back to Dec. 31 would “allow the San Diego County community particularly of former alumni of the campus such as me, former foster youth, current youth on the campus, stakeholders and county officials to come together with a little more time to make a plan for the future that could begin next year.”

Harris said the county should have told San Pasqual Academy staff and students about the change before many of them read it in the newspaper.

“The youth there should not have heard this in the media first, which is exactly what happened,” he said. “It’s wrong and it shows the failure of county officials to inform them first which they were entitled to know they would lose their home.”

A spokesman for Nathan Fletcher, the Board of Supervisors chairman, said the county received the state notification on Feb. 8 and the child-welfare director informed academy officials Feb. 19, two days before the Union-Tribune report.

Suzanne Miyasaki, the San Pasqual Academy principal, referred questions to the San Diego County Office of Education. The chief of staff there, Music Watson, confirmed in an email that the schools’ office learned of the state’s decision Feb. 19.

“Because (the county schools’ office) provides the educational program at the school and neither owns the facility nor oversees the residential program, we waited for additional information from the state and our partners at New Alternatives and the county of San Diego before notifying our employees who work at San Pasqual Academy,” Watson wrote.

San Diego County and New Alternatives, a nonprofit contractor that operates the school, would have been responsible for telling other employees about the planned closure, Watson said.

San Pasqual Academy has produced a number of graduates who have gone on to build productive lives. Its accomplishments have been a source of great pride for county child-welfare professionals, officials say.

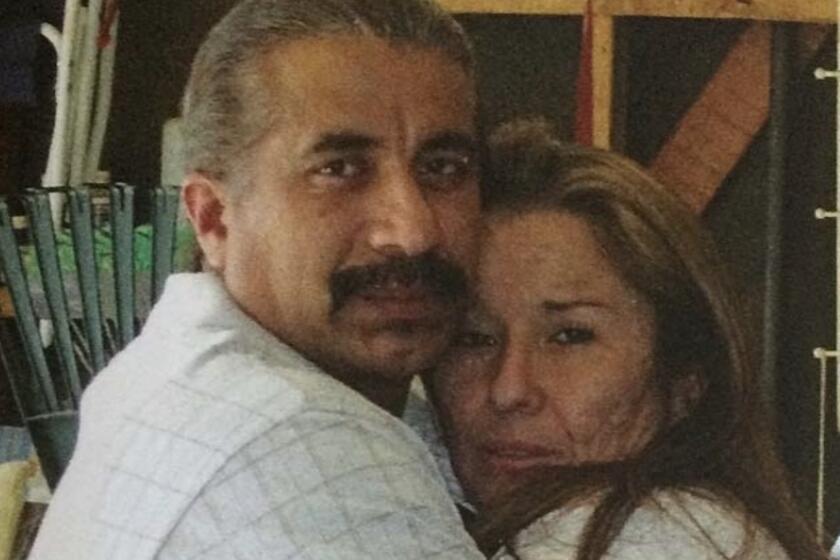

Kanesha Poe, 30, of Surprise, Ariz., said she was a San Diego County foster child living in a bridge shelter when she was 14 and the experience was “kind of scary.” She said she felt lucky to move into the academy, a place other children in the bridge shelter only dreamed of attending.

“You just always hear stories from the other kids who you’re like, locked up with,” she said of her time at the shelter. “It was like, ‘I almost got in there but I had to go to juvie,’ or, ‘I really wanted to go there but I got in trouble,’ so I was really happy to get the opportunity.”

Poe said academy teachers worked with her to make sure she got good scores on college entrance exams, taught her about credit scores, how to balance a checkbook, how to use a computer and other skills needed to live independently. They also helped her get a job at what is now called the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

San Diego County is planning to use the savings it expects from the school’s $13-million annual budget to fund expanded and improved services for families — and for all foster children 12 years old or older, not just those who are accepted into the academy.

Possible uses for the savings include expanding the partnership with the county Office of Education, providing older children more independent living skills and boosting services for foster families. The county may also increase scholarships and life-skills coaching for young adults who age out of the system.

Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, said research has consistently found that institutionalizing children is not as good for them as placing them with families. He said the county could put the academy’s budget to better use by keeping children out of foster care and safe with their families.

“It’s not surprising that study after study has found that even small amounts of money to ameliorate the worst aspects of poverty go a long way to reducing what authorities define as ‘child abuse’ because poverty itself is often confused with neglect,” he said in an email.

For example, the savings could be used to subsidize rent or provide childcare for 1,000 children per year, Wexler said. Or the county could follow Alabama’s example and provide “flex funds” – one-shot cash infusions for families to find better housing, pay late utility bills or meet other immediate needs, he said.

The child-welfare reformer also suggested directing those savings to high-quality legal representation for children and families, to keep children out of foster care without compromising safety or a drug treatment facility where parents can stay with their children while they recover.

The greater San Diego County child welfare system, which serves thousands of children, has a history of mismanagement and devastating failures that have resulted in lawsuits and legal settlements.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.