Gotta go: inside downtown San Diego’s public bathrooms

In life, the only certainties are death, taxes and the fact that everyone needs a place to do their business. But finding a clean public loo downtown? That’s an uncertainty.

In life, the only certainties are death, taxes and the fact that — often at an inconvenient, gut-clenching moment — everyone needs a place to do their business.

“Sir, relax,” Herbert Bridges told a pedestrian racing to a public restroom outside San Diego City Hall.

The security guard unlocked a steel door, revealing a cinder block chamber with a stainless steel commode, urinal and sink. Brown stains marked the walls, litter and dark patches the floor.

“Everybody’s panicked,” Bridges commented, “but I got it under control.”

When it comes to public restrooms, critics insist, San Diego cannot say the same. In 2005 and again in 2015, San Diego County’s grand jury urged more public bathrooms downtown. Similar pleas came from the East Village Redevelopment Homeless Advisory Committee (2001), the San Diego Partnership’s Clean & Safe Program (2005) and the Girls Think Tank (2009).

This shortage was cited as a factor behind 2017’s hepatitis A epidemic. During that crisis, the city installed dozens of portable restrooms and outdoor washing stations. Yet relief was only temporary.

“Immediately after the epidemic, we saw many of the Porta Potties and hand-washing stations were removed,” said Mitchelle Woodson, interim executive director for the nonprofit Think Dignity, the re-named Girls Think Tank. “I don’t see that we’ve made any progress.”

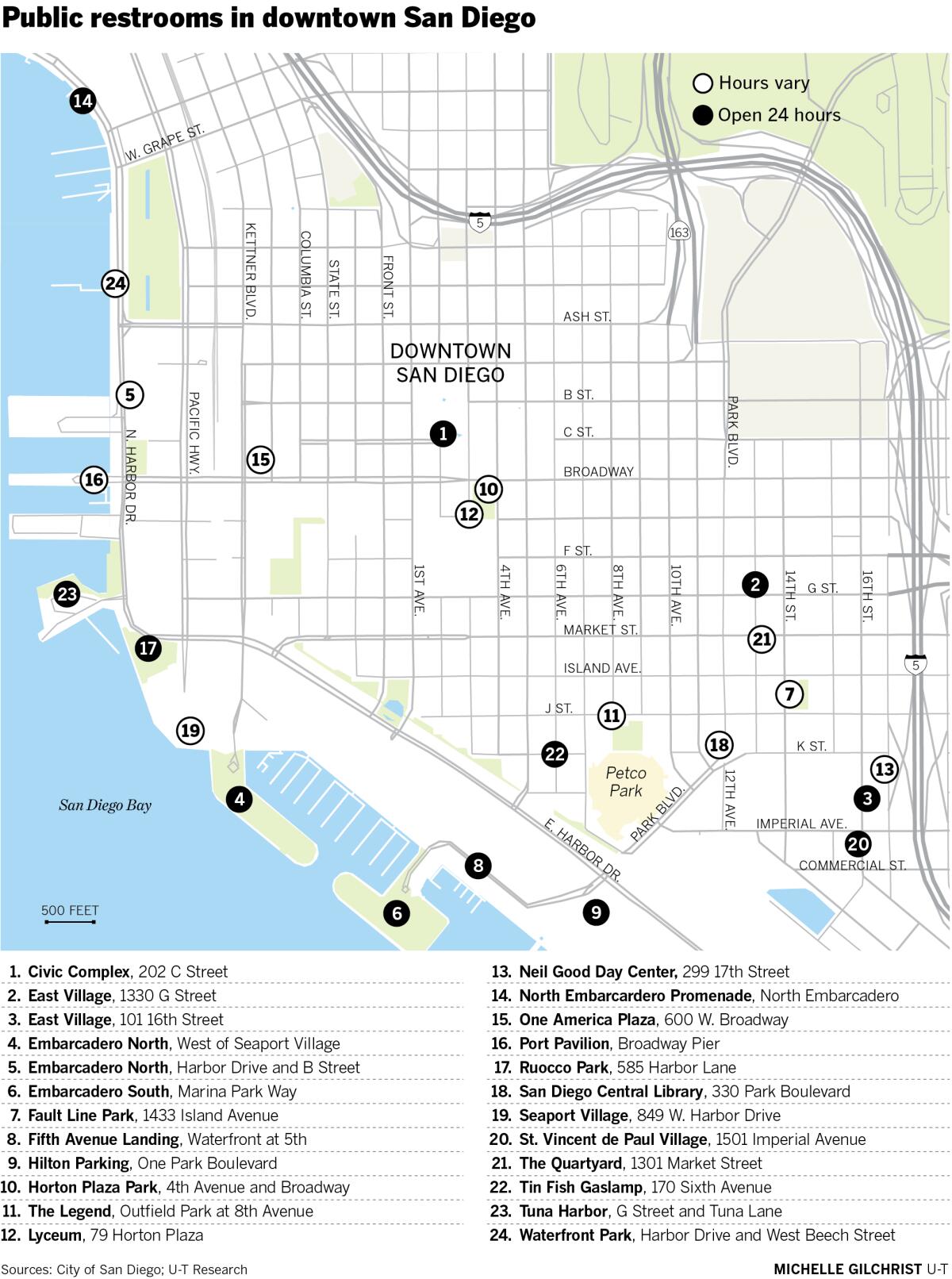

Between the harbor and East Village, city officials list 21 sites offering public restrooms. This tally is incomplete, as researchers found several other spots, and no single agency takes responsibility for this patchwork network. Facilities are managed by the City of San Diego, the Port of San Diego, County of San Diego, St. Vincent de Paul, Pinnacle Development, East Village Square Association, the Irvine Company, even the San Diego Repertory Theatre.

Some restrooms are spotless — Seaport Village’s facilities are scrubbed every half hour — while others resemble prison cells, post-riot.

If you’re downtown and in need, you have many options. Some come as pleasant surprises. Others?

“They’re as bad as they’ve ever been,” said Pete Powell, a retired Washington state trooper and downtown resident. “We see it, with live with it.”

Along the bay

The waterfront is well stocked with restrooms, but they vary considerably in cleanliness and aesthetic appeal.

At the far northwest end, opposite Solar Turbine’s headquarters, there’s a trashed facility. The floor is ankle-deep in discarded toilet paper; the sink overflows with empty snack wrappers and other refuse; the soap dispenser was smashed.

There’s no on-site security. Instead, this Port-managed restroom had a sign encouraging patrons to “report non-emergency problems, offer suggestions or make comments” on a posted “24-hour comment line.”

That number, (619) 725-6099? No longer in service.

A mile south on Harbor Drive, by Carnitas Snack Shack, there’s an entirely different restroom experience. Here, the Port and the city joined forces on a $2 million box-like structure, its eye-catching exterior decorated with oversized letters, its interior brightened by reddish-orange tiles.

This place is tidy, but don’t expect a recent Canadian tourist to write home about it.

“It was fine, clean enough,” said Erickson, a retired businesswoman from Vancouver, B.C., whose 23-day cruise aboard Holland America’s Volendam stopped here. “It didn’t smell or anything.”

Also clean: the county-run restrooms at Waterfront Park. On both north and south sides of the County Adminstration building, there are new men’s rooms, women’s rooms and separate family rooms, the latter equipped with changing tables.

South of the USS Midway Museum, restrooms offer a study in contracts. In Tuna Harbor Park, homeless men and women linger outside the bare cinder block facilities.

“It’s on the low end of the expectations spectrum,” said Brian Hogan, a visitor from Hartford, Conn. “But it worked. The water flushed.”

Wedged between this site and Seaport Village is Ruocco Park, where the facilities were pleasing to look at (clean, freshly painted) and frustrating to use (no soap, broken air driers).

Seaport Village’s three separate facilities — next to the Wyland Galleries, Cariloha Bamboo, and the Village’s offices — are in tip-top shape. The sinks have faux marble countertops; the tile floors are mopped to a Mr. Clean-like shine; there are paper towels and (working) air driers. The air is scented with something floral, rather than — as is too often the case — something fecal.

Another laudatory lavatory along the bay: the Hilton San Diego Bayfront. The public rooms here are tough to find, tucked under the ramp drivers use to approach the resort’s main entrance, and difficult to enter — you need a token from one of the ground floor businesses. Once inside you’ll find a quiet, scrubbed, spacious area to perform your ablutions.

Center city

In 1992, Kelly Conklin suffered a head injury. After coming out of a coma, Conklin found she had lost her Rancho Bernardo home and her business, a day care center. Today, she spends her days in a wheelchair and her nights in a 2006 Toyota Corolla. She relies on public restrooms, including the ones outside City Hall.

She can overlook the grit and garbage, as long as there’s round-the-clock security.

“I don’t care if you in the Garden of Eden,” she said. “You need to have a security guard.”

Filthy as they are, these may be the most popular restrooms in town. Bridges, the guard, estimates they attract 250 patrons a day — homeless individuals like Conklin, but also tourists and the occasional City Hall-bound visitors.

“The mayor comes by here every day,” Bridges said. “He won’t use the restrooms — I don’t blame him.”

The facilities behind Tin Fish are equally grimy. There, Lee Ann Alirez sometimes uses a cup and the sink’s cold water to clean herself.

“You can get a real shower in there,” she said, “if you use a cup fast enough.”

Fastidious visitors might recoil from the grit-encrusted walls of this Gaslamp Quarter restroom. Far more sanitary are the city’s facilities in Horton Plaza Park, where there are separate men’s, women’s and family rooms. Security was on site during a recent visit, which pleased Willie Chammon.

“You get a lot of young kids that like to stay in there, like this is some gambling shed, like some lounge,” said Chammon, 51, who lives on the street. “It’s better now, because you’ve got security guards.”

Safety concerns are part of what makes public restrooms so expensive. In 2014, the city installed the first of two self-contained “Portland Loos” in the East Village. Soon, police calls to the area rose 130 percent as the facility was used for drug dealing, prostitution and other crimes.

The city had bought that Loo and a second, which debuted in 2015, for $560,000; hundreds of thousands more were spent maintaining the two. By 2017, both were scrapped.

Yet eliminating bathrooms does not eliminate crime. On a recent night, a man in ragged clothes entered Ogawashi Sushi, a restaurant on the corner of C Street and Fifth Avenue. Claire Lim, the manager, told him that restrooms were reserved for customers. The man erupted.

“He started screaming and being aggressive,” Lim said. “He starts cursing at me.”

Hours after he stormed out, someone smashed one of the restaurant’s windows.

The glass has been replaced. Prominently displayed on the window is a hand-lettered sign: “No Public Restrooms.”

East Village

To maintain downtown’s public restrooms, the City of San Diego estimates it spends almost $110,000 a month. That’s plenty of money, but less than other cities spend — San Francisco estimates that the annual cost of operating a single public toilet is $170,000 to $205,000.

To save tax dollars, that city’s Pit Stop program offers a deal to private parties. In exchange for shouldering the expenses of 25 self-cleaning toilets, contractors are allowed to operate kiosk stands on San Francisco’s sidewalks.

In San Diego, outside entities cover some costs. The attendant at the two unisex bathrooms in East Village’s Faultline Park, for instance, is supplied by Pinnacle, the developer of nearby condos.

The city also relies on people like DeShawn Jones. A 32-year-old resident of St. Vincent de Paul Village, he recently volunteered to clean that shelter’s restrooms. He said he doesn’t mind — “Everyone living here does something,” Jones said — but the job is daunting.

“I try to clean every two hours,” he said. “It gets bad.”

At the Central Library, staff is responsible for cleaning and supervising the restrooms found on every floor. On a recent afternoon, they looked functional and clean and — on the first floor — unique. In the ground floor children’s section, there are three washrooms: a kids room with pint-sized sink and commode; a family room with a changing table; and a room for nursing mothers.

Large or small, putrid or pristine, used by the well-heeled residents or the down-on-their-heels, these facilities all address a basic human need.

“We are in a very anti-homeless climate, which makes it difficul to deal with this issue,” said Think Dignity’s Woodson. “We are trying to reshape that narrative. People have a lack of necessary facilities. It is beneficial to the entire community to change that.”

The latest news, as soon as it breaks.

Get our email alerts straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.