San Diego has a long history with white supremacists

For some San Diego County residents, the recent synagogue shooting in Poway -- allegedly by a 19-year-old college student immersed in anti-Semitic, racist beliefs -- is a painful reminder that this corner of the United States has long been fertile ground for white supremacists.

The Ku Klux Klan arrived here in the 1920s, targeting Mexican immigrants, and remained a presence for decades. A television repairman ran the influential 1980s separatist group, White Aryan Resistance, from Fallbrook. A 25-year-old in Lemon Grove was deemed by national watchdog groups “a rising star among bigots” in the early 2000s for using cyberspace instead of in-person meetings to recruit and encourage followers.

At one point in the early 2000s, the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups, identified six of the “pillars of the old guard” among white supremacists nationwide. Two of them were in Escondido. Recently, an Iraq War veteran with San Diego ties founded the group Identity Evropa, whose members helped plan the deadly 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville.

Every community of any size has spasms of extremism, but they’ve been common enough in San Diego County to merit special attention from local officials. Law enforcement here was among the first in the nation to create a hate-crime prosecution unit, first to have a countywide protocol for responding to and investigating hate crimes, and first to designate hate-crime specialists in each San Diego police or sheriff’s station. A case out of San Diego County involving a man who beat three farm workers in Alpine established the constitutionality of the state’s hate-crime enhancement law in the 1990s.

Still, the problem persists. Hate crimes went up 15 percent in the county in 2017, according to data from the FBI and the state Department of Justice.

Experts say a variety of factors have contributed to San Diego’s historical influence in the world of white supremacy. It is the second-largest city in the nation’s most populous state, which means there are more people of all kinds here -- even haters. The changing demographics of Southern California make it a hotbed for extremists looking to blame someone for their changing fortunes, economic and otherwise. The proximity to the border makes it attractive to some who want to agitate about immigration.

The result has been a steady stream of incidents over the years in almost every corner of the county. Latino laborers attacked by pellet-gun wielding white youths in the North County. A black Marine left paralyzed after a beating by five white men during a party in Santee. And now one Jewish woman killed and three people injured in the attack at Chabad of Poway on the last day of Passover.

“The horrible incident in Poway just brings it all back for me, as I’m sure it does for a lot of other people in the county,” said Serge Dedina, the mayor of Imperial Beach, who witnessed a racism-fueled shooting as a teen in that town and then grew up to see his own campaign targeted with anti-Semitic fliers. “White supremacy and racism have been pervasive here, and we haven’t always taken them as seriously as we should or talked about them in terms of a pattern.”

Ku Klux Klan

Newspaper archives show that the Klan made its first public appearance in San Diego on Christmas Day in 1922, hosting more than 100 people for dinner at a local hotel.

Many of its other activities were less charitable, according to a 2000 article in the Journal of San Diego History.

Authors Carlos Larralde and Richard Griswold del Castillo detail how the group -- known officially as the Exalted Cyclops of San Diego No. 64 -- went after Mexican immigrants crossing the border to work, harassing them on horseback in cone-shaped hoods. There were reports of beatings, torture, lynchings and Mexicans who disappeared. Homes and barns were torched.

Members belonged to churches, owned businesses, and worked for local governments, according to the article. Many were new arrivals to California themselves, whites from the Midwest who found in the Klan “a solution for the anxieties they felt as they encountered a new environment and new peoples.”

In the 1930s, like-minded groups emerged, including one called the Silver Shirts League of San Diego, which drew inspiration from the Nazis in Germany and some of its members from the Klan. They held public rallies and private rituals with swastika-decorated flags and deemed it their mission to “cleanse society of undesirable characters,” including blacks and Jews, according to the Journal article.

Klans flourished in Southern California during the 1940s and 1950s, with members running for Congress in Los Angeles and members in San Diego undermining local labor unions and rooting out communists. After a spate of cross burnings in Los Angeles, authorities cracked down, revoking the organization’s charter to operate in the state, and its activities went largely under cover.

By the 1970s, though, some Marines at Camp Pendleton openly advertised their membership in the group. They wore KKK insignia and posted fliers threatening to blacks. In 1976, a group of 14 black Marines stormed into a room on the base where they thought the Klan was meeting and beat a half-dozen whites there. They had the wrong room.

Thirteen of the Marines were jailed and charged with crimes. The Klan members were put in protective custody and shipped to other bases, according to news reports at the time. It wasn’t against regulations then to belong to an extremist group. It is now.

Oceanside was also the site of a Klan-related riot in 1980. About 50 Klansmen rallying at John Landes Park got into a rock-and bottle-throwing brawl with 200 anti-Klan protesters. One of the protesters was seriously injured. Police shot and killed a Doberman held by a Klan member after it attacked a police dog and its handler.

The leader of the Klan told reporters that the melee was “worth it to stand up for freedom of speech and freedom of assembly. We’d do it again.”

His name was Tom Metzger.

A spin-off

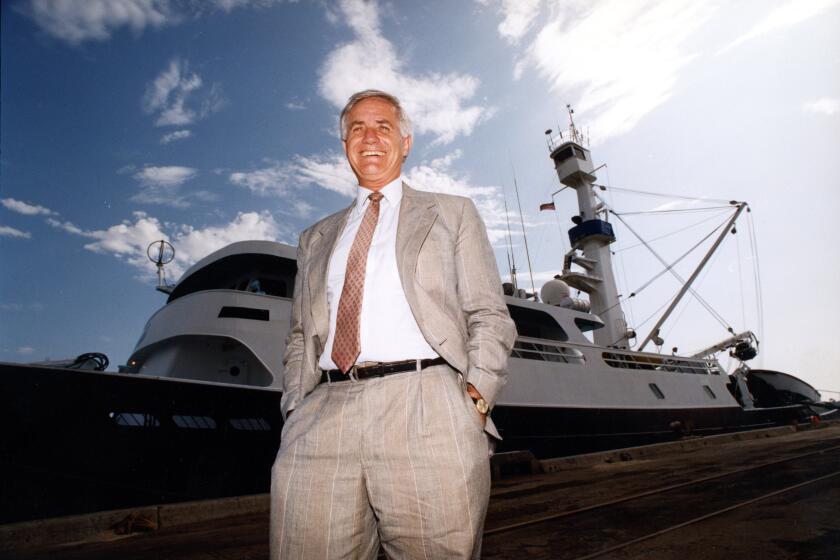

Metzger, a television repairman, made national headlines in 1980 when he won the Democratic primary for a North County seat in Congress. He was trounced in the general election, but his profile grew in certain circles. He started his own group, which eventually became known as White Aryan Resistance. Its acronym, WAR, was entirely intentional.

“We are in a white civil war,” Metzger said on one of the many telephone “hotline” messages he recorded for followers to hear. “Our white leaders are traitors to their race and Jews assist them in our destruction.”

By the late-1980s, Metzger was considered one of the most influential white separatists in the country, collecting more than $100,000 in donations annually, most of it in cash. His weekly cable TV show, “Race and Reason,” was shown in 31 major markets -- Chicago, Pittsburgh, Boston, Seattle, Los Angeles -- and accounted for more than half of the hate programming nationwide, according to a study by the Anti-Defamation League.

He also spread his message through a newspaper, pamphlets and, later, a website. He became so notorious that at least one San Diegan whose last name was Metzger changed it because she didn’t want people to think she was related.

Many of his followers were young skinheads. In 1988, three of them in Portland, Ore., chose a black man at random -- a 27-year-old college student from Ethiopia named Mulugeta Seraw -- and beat him to death. They pleaded guilty.

Lawyers representing the family, including Jim McElroy, a civil-rights attorney in San Diego, then sued Metzger and his son, John, in civil court for inciting the killers. They used bank and phone records to link them. A jury awarded the family $12.5 million in 1990.

Metzger was forced into bankruptcy. He lost his home, a trailer in Rainbow where his group held meetings, television equipment and other belongings. Donations to WAR were seized.

He remained active in white supremacy causes. In 1991, he was convicted of unlawful assembly for his participation in a cross-burning near Los Angeles and sentenced to six months in jail. As a condition of his probation, he was required to quit any neo-Nazi or Klan-like groups. His influence nationally waned.

But he remained a role model for young followers in San Diego. One of them, a 15-year-old La Mesa boy, was caught putting racist fliers on hundreds of cars at Cal State San Marcos in 1997. “Let’s make San Marcos State a White school for White students,” one message said. “The few remaining mud-colored profs can be harassed out of here.”

The teen told campus police he was a member of WAR. Metzger, contacted by a reporter, denied any involvement in the incident, but he expressed his support. “I’m all for it,” he said.

In 2006, Metzger moved to Indiana to live in a home he inherited from his mother.

The new breed

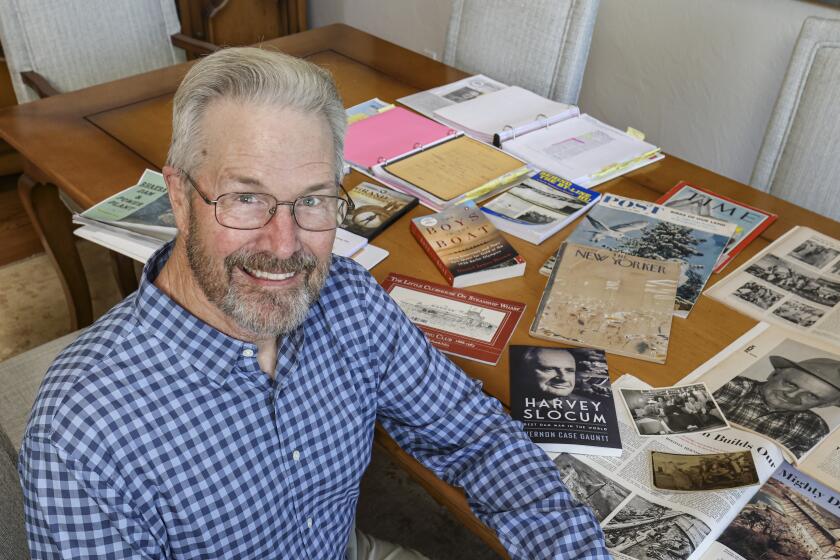

Alex Curtis was 25 and living with his parents in Lemon Grove when the Southern Poverty Law Center named him one of the nation’s six most prominent young hate leaders in 2000. The ADL called him “a rising star among bigots.”

He’d first created a stir seven years earlier when two classrooms at Helix High -- decorated with images celebrating the contributions of minorities -- were vandalized. Swastikas were spray-painted on the walls. A note left in a drawer read: “The Ku Klux Klan is watching and we’re not happy about what we see.”

Linked to the break-ins, Curtis was expelled. Four years later, while then a college student, he was convicted of illegally using a La Mesa police insignia and phone number on a flier that claimed the city was turning into a “nonwhite sewer.”

In an office that used to be the laundry room of his parents’ house, Curtis spread his views through a website, a magazine and a telephone hotline. Authorities said he was at the forefront of a new breed of white supremacists who recruit through the Internet, avoid public rallies and meetings, and encourage “lone wolf” attacks that are hard to trace.

“Almost every magazine or group tries to deny their hate and soft-pedals their racism,” Curtis told a Union-Tribune reporter in an e-mail interview in 2000. “I attack my enemies, such as the U.S. government and Jews, without compromise.”

Weeks later, he and three other men were arrested on federal civil rights charges. The FBI said the suspects ran a three-year campaign of harassment that included leaving threatening and racist messages at the homes or offices of four local civic leaders. One received a dummy grenade in the mail. Another found a 7-foot-long snakeskin draped over a rose bush in her front yard. The suspects were also accused of painting anti-Semitic images and slogans at two area synagogues.

Curtis, according to authorities, “told his followers to use whatever means necessary to accomplish their white supremacist goals.” When agents searched his home, they found a portrait of Metzger.

Facing 10 years in prison, Curtis pleaded guilty to three conspiracy charges and was sentenced instead to three years. “You’re vivid proof that the white race is not superior,” the judge told him.

One of the victims in the case was Morris Casuto, then the regional director of the local ADL, whose home and office had been defaced with swastika stickers and fliers.

Casuto said in an interview last week that hatemongers kept him busy during the 37 years he ran the office before retiring in 2010. He also said San Diego was “ahead of the curve” in its response via hate-crime prosecutions, hate-crime registries and other approaches.

But he sees a troubling change in the most recent attacks.

“In the past, what we had was individuals who attacked buildings and institutions,” he said. “They went after mortar and stone. Now they are going for people.”

Staff researcher Merrie Monteagudo contributed to this report.

The latest news, as soon as it breaks.

Get our email alerts straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.