Planning groups face reforms to encourage renters, young people, minorities

Proposal would fundamentally change role of neighborhood voices in key San Diego decisions

San Diego is considering fundamental changes to the city’s 42 neighborhood planning groups that would alter how the groups operate and how they provide crucial input to the City Council before key votes.

Supporters say the changes would make the groups more transparent, better organized and less likely to oppose dense developments the city is pursuing to help solve its housing crisis.

The changes also aim to boost demographic diversity by requiring more aggressive term limits and encouraging the groups, which are primarily made up of White homeowners, to recruit more minorities and more renters.

Critics say the changes would severely burden the volunteer groups and create membership goals akin to quotas.

They also say some groups, particularly in low-income areas, could be overwhelmed and forced out of existence.

Some suggest the changes are being pushed by the development community to streamline the approval process for new housing and other projects by limiting opportunities for neighborhood opposition.

The proposed changes, which are expected to go the City Council for a vote later this year, were sparked by complaints from the city auditor and the county grand jury that the planning groups are unprofessional, unpredictable and not adequately transparent.

More than 30 policy changes recommended for community planning groups

The groups also have been criticized for seeking to block housing projects too aggressively and for having stagnant membership that doesn’t accurately reflect the neighborhoods they represent.

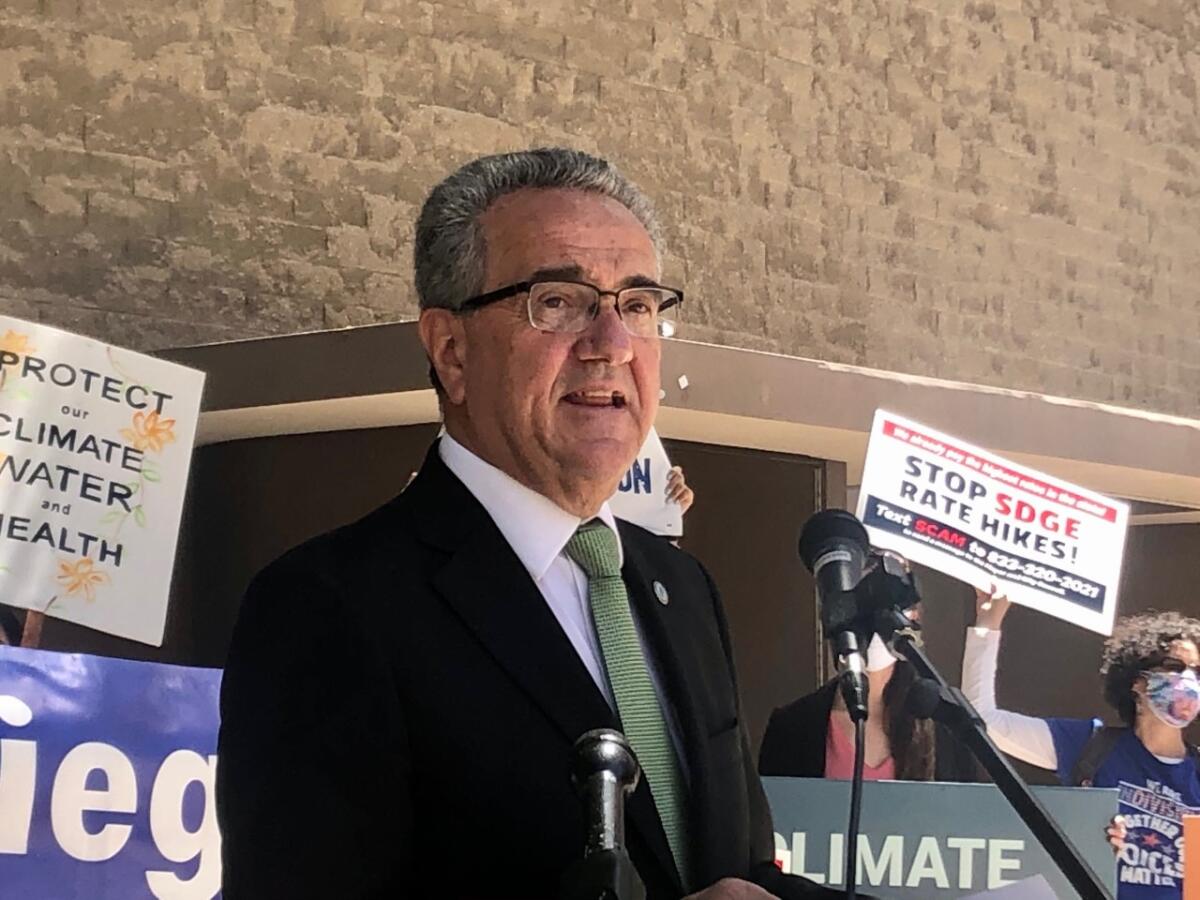

Councilmember Joe LaCava, who is spearheading the effort, said he believes the changes will keep the planning groups robust and important, while also making them more representative, independent and accountable.

“It’s a fundamental change in many ways,” LaCava told the council’s Land Use and Housing Committee last week.

Wally Wulfeck, leader of an umbrella panel that represents all 42 of the city’s community planning groups, said he thinks the proposal is too extreme and that any problems with the groups could be solved with more modest changes.

“The proposals actively deter longtime residents who are interested in their communities, but they provide no incentive for supposedly underrepresented volunteers to get engaged,” he said.

Wulfeck said many of the changes would be counterproductive.

“There are a lot of requirements that are burdensome, and in some cases really obnoxious, but nothing proactive to help anybody,” he said. “The biggest problem is that it basically severs the relationships between the city and the CPGs that have existed since 1966.”

Regarding burdens, Wulfeck is referring to new requirements that the groups post their own meeting agendas, handle their own recordkeeping and take on other duties that have been handled by city officials for decades.

The groups also would no longer have the power to appeal decisions by the Planning Commission to the City Council without paying the hefty appeals fee required of everyone else.

LaCava and City Attorney Mara Elliott say greater independence for the groups is required by the city charter.

Councilmember Vivian Moreno said she’s worried that low-income areas, which are often ethnically diverse, may get overwhelmed if they have community leaders who are less familiar with the new tasks and technical requirements.

She also noted that her district, South Bay District 8, is dominated by working people with families who will be more reluctant to join a neighborhood planning group if the time commitment is too large.

Heidi Vonblum, the city’s interim planning director, said her staff would be willing to help planning group leaders. But Deputy City Attorney Corrine Neuffer said such help could be a problem.

“The more the city is involved in their operations, the less likely they would be considered independent, and at some point there would be a tipping point,” Neuffer said.

Three other key parts of the proposal aim to make significant changes in who joins the groups.

Term limits would be tightened, including a requirement that members who hit the cap — usually eight or nine years — be ineligible to serve for two years.

The requirements to serve on a group’s board and to vote in board elections would be softened to eliminate rules that say a person must have previously attended a group meeting.

And groups would be required to revise their bylaws to designate seats for renters, nonprofit groups and other organizations, and to create recruitment plans to help fill those seats. The designated seats would be a goal, not a requirement.

Some planning group members called the changes too extreme, but others said they are necessary to make the groups more diverse and more reflective of the communities they represent.

Leana Cortez, a UC-San Diego student who attends meetings of the planning group in University City, said the existing rules discourage renters, minorities and young people.

“It’s not about lack of interest, it’s about exclusionary structures,” she said.

But Mario Ingrasci, leader of the Eastern Area Community Planning Group, said it is difficult to find renters and young people willing to attend meetings.

“We would love to have young people, and we would love to have renters — we just don’t know how to get them,” Ingrasci said. “We’ve been trying, but we haven’t found a way.”

Advocates for dense housing praised LaCava’s proposal.

Ryan Clumpner, vice chair of the Housing Commission, said the planning groups need reform because they typically represent a small minority of the population with outdated ideas and priorities.

“One of the greatest challenges facing the equitable distribution of affordable housing is the opposition from community planning groups,” Clumpner said. “They often delay, downsize or outright kill off housing, especially in the northern districts.”

Matt Adams, a vice president for the Building Industry Association, agreed.

“We need to bring some fresh eyes and fresh perspectives to the planning group process,” he said. “Planning groups typically don’t reflect the diversity of the communities they represent.”

Wulfeck, leader of the planning group umbrella organization, the Community Planners Committee, said reducing citizen involvement and inclusion in city government is not the right way to streamline approvals.

“My personal opinion is that most of this is being pushed by the Planning Department and industries and organizations that benefit from pro-density, massive housing development, in order to get any community opposition out of the way quickly,” he said.

LaCava plans to present the proposal to the Land Use and Housing Committee for a vote in coming months. It would then go to the full council for final approval.

Planning groups would have until sometime in 2023 to begin complying with the new requirements and policies.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.