Will Cal Fire’s plan to rip out vegetation in San Diego lead to an explosion in flammable invasive grasses?

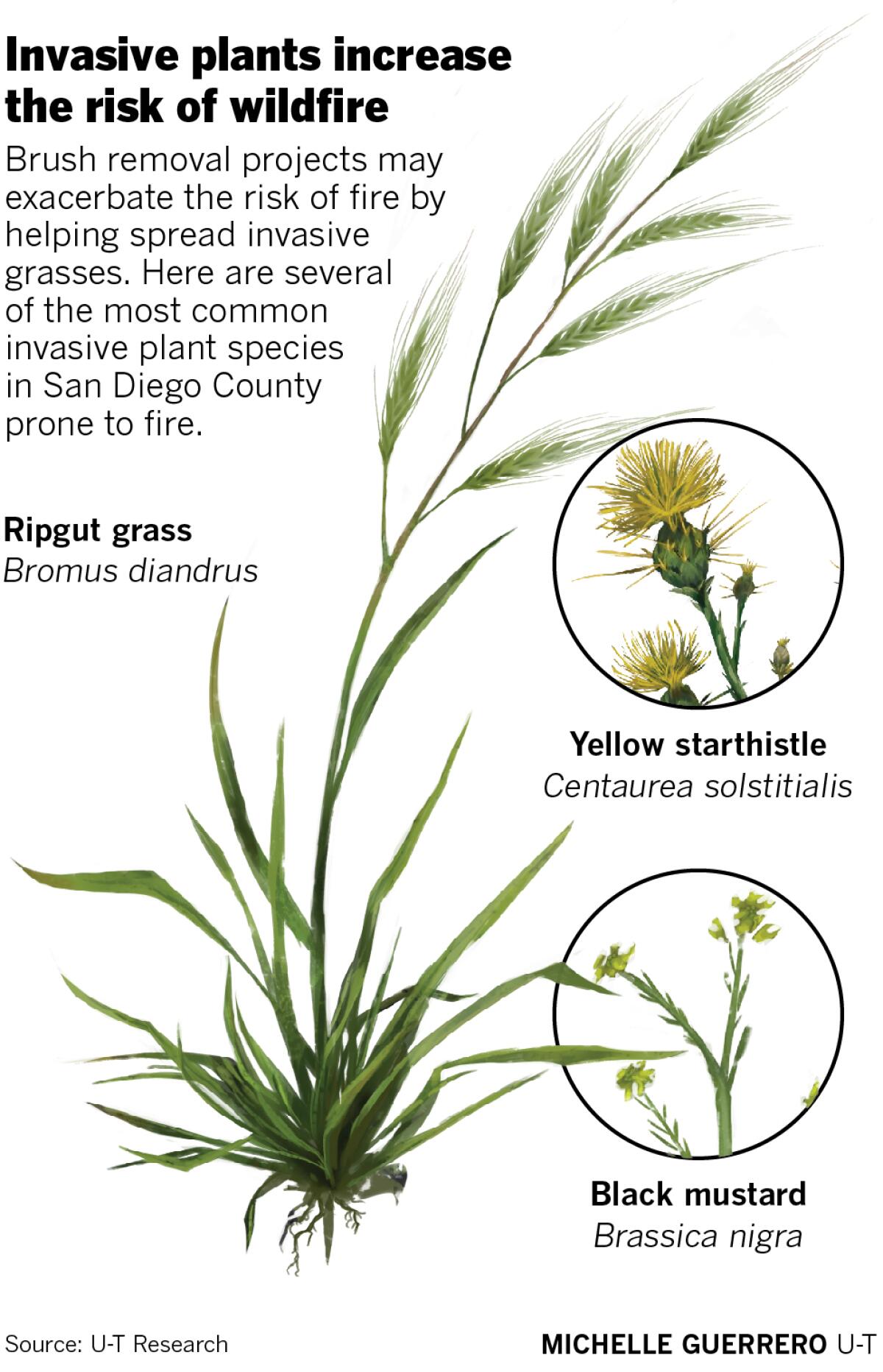

Southern California is grappling with a proliferation of easily ignited black mustard, ripgut, star thistle and other invasive plants displacing native habitat

Highly flammable nonnative plants have increasingly played a major role in Southern California’s struggles with wildfire — providing kindling along roadsides and around homes that turn sparks into menacing backcountry blazes.

San Diego firefighting officials plan to dramatically ramp up efforts to rip out vegetation, both native and invasive, surrounding remote communities as part of a statewide campaign to prevent tragedies such as the Camp Fire in Paradise.

However, environmental groups and scientists are now warning that brush-removal projects may actually exacerbate the risk of fire by inadvertently helping to spread invasive grasses, such as black mustard, star thistle and ripgut bromus.

San Diego County’s ambitious goal is to clear 5,000 acres a year around the county using prescribed burns and chainsaws, while also ramping up maintenance of trails and remote roads accessed by firetrucks.

Critics say the plan is ill-conceived and seeks to bypass environmental reviews that could force authorities to address the spread of invasive plants.

“They just released a new strategy plan. Not a word in there about this situation,” said Rick Halsey, director of the San Diego-based California Chaparral Institute. “Once again, they want to expedite environmental procedures so they can go out there and clear habitat.”

Officials with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, known as Cal Fire, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

County officials downplayed the notion that invasive grasses could be playing an outsized role in wildfire.

“From a fire standpoint, County Fire/Cal Fire San Diego Unit is concerned about any vegetation that can potentially contribute to the spread of wildfire,” county spokeswoman Tammy Glenn said in an email. “Non-native annual grasses have historically been a part of California’s grasslands since their introduction during Euro-American settlement centuries ago.”

To illustrate his concerns, Halsey drove out along state Route 78 on Wednesday to the rolling hills between Escondido and Ramona. There large swaths of countryside were burned in the 2007 Witch Fire, with some sections scorched again by smaller blazes in following years.

As result of the fires, Halsey said, invasive plants had proliferated. Indeed, grasses, turned golden brown in the late summer heat, flowed over many of the slopes, interrupted only by sparse patches of green, native chaparral, such as chamise and laurel sumac.

“This is just too much fire for this spot,” he said, “so you’ve lost a lot of biodiversity. Plus you have a much more flammable situation. There’s going to be another fire here in 10 years.”

This same pattern will likely play out in many of the areas where Cal Fire wants to clear out brush and use prescribed burns, Halsey argued.

Chaparral and sage scrub include what are known as fire-adapted species, meaning wildfire is essential for the health of the plants. But the fire regimes of invasive grasses, Halsey said, are different than those of native plants, burning more frequently, faster and at lower temperatures.

As the head of the Chaparral Institute, his opposition is strongly informed by a mission to protect native chaparral and coastal sage scrub habitat, which service everything from the gnatcatchers to trapdoor spiders.

However, scientific researchers have also come to similar conclusions about the spread of invasive grasses and the role they’re playing in spreading wildfire.

“It’s the never-ending cycle where the more (invasive plants) burn, the more you have, the less you have of everything else, the more frequent and unpredictable your fires become,” said Travis Bean, UC Cooperative Extension weed science specialist based at UC Riverside. “It quickly gets out of control.”

More than 90 percent of wildfires are caused by people, most often when humans routinely come into contact with the edges of forests and wildlands.

Bean said that this recipe for disaster most frequently plays out along roadsides lined with invasive grasses, where sparks, cigarette butts and other potential ignition sources from vehicles can easily bring catastrophic results.

“It’s like we drizzle all our roadsides with just a little bit of lighter fluid,” he said. “If we don’t manage them, the fire’s going to get off the roadside and into that chaparral, climb up that hill and get into that multimillion-dollar housing development.”

The catch for those engaged in brush management is that once you alter an ecosystem, whether building a road or creating fuel breaks for firefighters, routine upkeep becomes essential in order to keep invasive plants from taking over, Bean said.

“Once you perturb the system,” he said, “It’s going to be a constant annual, sometimes more than annual, maintenance scenario that now should be considered a part of your budget forever. Otherwise, in the luckiest case scenario the native chaparral grows back. More likely, it’s going to get invaded by these easily ignited species.”

Even more likely is a situation where there is a mix of invasive grasses and the more hardy native bushes, Bean said. “That can be even worse because you get that quick flash of ignition from the fine fuels and the heat retention and staying power of the chaparral species.”

“It’s like we drizzle all our roadsides with just a little bit of lighter fluid.”

— Travis Bean, UC Cooperative Extension weed science specialist based at UC Riverside

County officials said that they revisit treated areas every three to five years.

“This ensures that the breaks continue to serve their intended purpose,” said Glenn with the county. “Fuel breaks act as a buffer against the spread of wildfires, helping to protect nearby communities, including critical infrastructure and sensitive habitats.”

California kicked off its campaign to more aggressively prune back forests and scrublands this summer. Gov. Gavin Newsom waived the environmental review for 35 so-called fuel-management projects across the state.

In San Diego County, Cal Fire cut down large swaths of vegetation around the communities of Crest and Guatay. Firefighters cut 200-foot-wide fuel breaks around homes on a combined nearly 190 acres.

At the time, Cal Fire officials said they were selectively leaving some of the native plants in place.

Sabrina Drill, natural resources adviser for Los Angeles and Ventura counties for the University of California Cooperative Extension, said that grooming natural landscapes can, to a certain extent, help firefighters when battling blazes.

“I think there is a need to have established and maintained fire roads,” she said. “Fuel breaks around developed areas can be somewhat effective.”

Specifically, she said, that cutting back brush around homes can give firefighters staging from which to protect communities. However, she said if those areas aren’t regularly groomed, brush removal projects can lead to even more flammable conditions.

“I might suggest coming back in and spraying in future years when those annual grasses come in,” she said. “There needs to be a commitment, and it needs to be at least annual.”

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.