Congress calls for reform after 131 judges with stock holdings fail to recuse from cases

Fallout from Wall Street Journal investigation includes a proposed law that would make financial disclosures more transparent

Two months ago, the federal judiciary came under fire after a Wall Street Journal investigation found 131 judges — including two in San Diego — had failed to disqualify themselves from hearing cases involving companies in which they or their families held stock.

The revelations have spurred a bipartisan effort in Washington calling for greater transparency and accountability among federal judges when it comes to publicly reporting their stock ownership and their obligation to recuse when there is a conflict.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

While the Wall Street Journal’s investigation found no evidence that judges were intentionally deciding cases to bolster their own finances, lawmakers and experts stressed that even the appearance of impropriety can be enough to shake the public’s confidence in the judiciary.

“The damage has been done,” Georgia Democrat Rep. Hank Johnson — chair of the House’s Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet — concluded at a hearing last month.

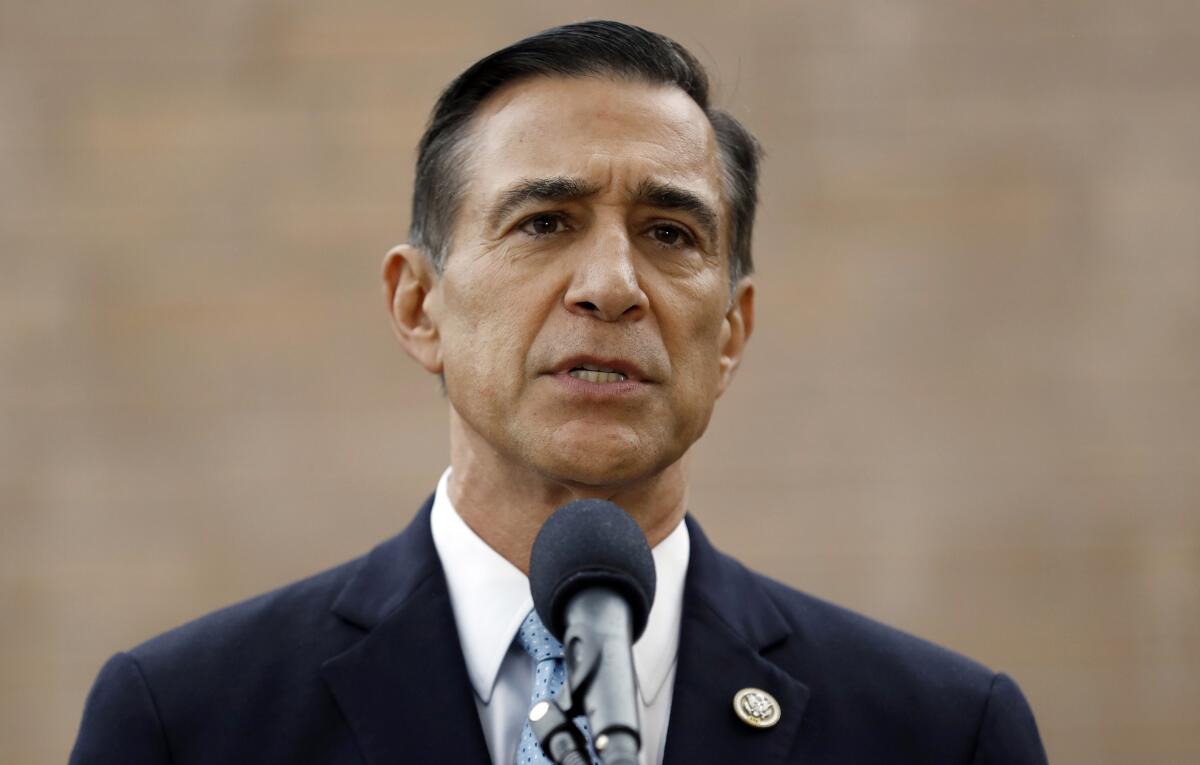

The subcommittee’s ranking member, Rep. Darrell Issa, is among the bicameral group of legislators spearheading a push for reform by co-sponsoring the Courthouse Ethics and Transparency Act, which is already moving through Congress.

“The administration of law and order rests upon the unbiased and unwavering work of judges — and that’s why we must maintain an impartial and evenhanded judiciary,” Issa, a Republican serving much of eastern San Diego County, said in a statement.

The proposed law seeks to address part of the failures exposed in the Journal’s extensive reporting, which involved journalists reviewing nine years of financial disclosure forms from about 700 judges compiled by the Free Law Project, a nonpartisan legal-research nonprofit. The Journal then compared the data to tens of thousands of civil court dockets to ascertain if judges had presided over lawsuits despite apparent conflicts of interest.

The investigation found that 131 judges had improperly failed to excuse themselves from overseeing 685 cases from 2010 to 2018. The companies involved included such giants as Exxon Mobil, Comcast, Ford Motor Co. and Microsoft.

U.S. District Court Judge Janis Sammartino in San Diego was among the handful of judges highlighted. She had the second-highest number of conflicts — 54 — behind a Texas judge’s 138.

While judicial financial disclosure forms are public record, they are not readily accessible for inspection and can take more than a year to be released upon request. Furthermore, judges are only required to submit their financial disclosures once per year under current law.

The Courthouse Ethics and Transparency Act would require the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts to create a searchable online database of judicial financial disclosure forms to be easily accessed by the public. Judges would also be held to the same standard as other federal officials by requiring them to file reports within 45 days of securities transactions over $1,000.

Earlier this month, the measure passed the House Judiciary Committee and will move to the full legislative body for discussion and vote. A companion Senate bill has yet to be considered in committee.

The measure could help build transparency and accountability, keeping financial disclosures more up-to-date and aiding litigants in researching for themselves whether a judge has a possible conflict, according to experts.

However, several lawmakers and experts have questioned if more is needed to make sure judges are correctly reporting their financial interests and recusing themselves as required under U.S. law and judicial ethics.

“Viewed in the aggregate, we can reach no other conclusion (than) the system is broken,” Renee Knake Jefferson, a professor at the University of Houston Law Center and expert on judicial ethics, testified during Oct. 26 hearing.

“We have a law on the books that federal judges have not complied with,” she added. “If anyone should be following the law I would think the public would expect judges to be following the law.”

Several of the judges contacted by the Wall Street Journal expressed dismay at learning they had not been in compliance. Many said they were unaware of their spouse’s stock holdings — which are still subject to disclosure. Others said they didn’t know that stocks in managed portfolios — in which decisions about what securities to hold are made by an investment professional, not the portfolio’s owner — had to be reported.

Sammartino gave both reasons as explanations.

She referred the Journal to a spokesperson for the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, who said that her stocks were in a managed account “so she’s not seeing as how there could be a conflict.”

Sammartino declined a request from the Union-Tribune to discuss the Journal’s findings. U.S. Chief District Judge Dana Sabraw in San Diego said the managed funds were held by Sammartino’s husband — a retired San Diego Superior Court judge whom she married late in life — and that she was not involved in or aware of his specific investments.

“She recognizes that is not an excuse under law,” Sabraw told the Union-Tribune. “She should have disclosed and recused early on in these cases, but because she didn’t know about those particular investments of her husband, she finds herself in this predicament.”

She and her husband have since divested of stock holdings and put their money in index or mutual funds, which generally aren’t subject to the recusal rules, Sabraw said.

Sammartino has also notified the clerk for the Southern District of California, who in turn notified litigants of more than 100 cases in which she has since learned a family member had financial interest and should have recused, including cases involving Qualcomm, Microsoft, Illumina, Pfizer, The GEO Group and JP Morgan Chase.

Many parties didn’t even file a response to the notification, while others wrote to the court that they weren’t seeking relief because they were comfortable with her assertion that she was unaware of the conflict when deciding the cases.

So far, at least two litigants — both representing themselves — have asked for their cases to be reviewed by other judges.

In one, a plaintiff asked for a settlement with Qualcomm in an employment discrimination lawsuit to be vacated, saying he had felt pressured at the time to settle. U.S. District Court Judge Gonzolo Curiel denied the motion last month, finding that Sammartino had no role in the settlement negotiations and made no substantive rulings in the case.

In another, a lawyer representing himself in a breach of contract lawsuit against Target has requested all of Sammartino’s substantive rulings be set aside.

“The key rulings have been strange for many reasons, not the least of which is that the Court’s reasoning has consistently strained to favor ‘Goliath’ (here, Defendant Target Corporation) rather than our side of the case (i.e., ‘David’),” wrote Stephen Lobbin. Another judge is reviewing his motion.

U.S. District Court Judge Roger Benitez in San Diego was also identified as having two conflicts. The Journal did not specify the cases or companies involved.

Benitez, who went on semi-retired status as a senior judge in 2018, told the Journal that the cases were too old for him to recall specific details. In one case, he granted an unopposed motion to dismiss and in the other case he dismissed the plaintiff’s handwritten complaint against several companies as frivolous, according to the Journal.

Benitez declined to elaborate further to the Union-Tribune, saying he stands by his comments to the Journal.

Sabraw said the judiciary’s obligation of identifying financial conflicts has been revisited in the weeks following the Journal’s investigation.

“It’s very important to us and we’ve discussed it at several meetings,” he said, “and we’re really motivated to get it right.”

The investigation has spurred training on disclosure obligations in courts across the country, according to 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Jennifer Elrod, who chairs the Committee on Codes of Conduct for the Judicial Conference, the policy-making body of the U.S. courts.

“We don’t want any judge to be ignorant of the rules regarding financial holdings,” Elrod testified.

“It is crucial for the integrity of the judiciary that we comply with our obligations ... Litigants need to know that they have judges who will fairly hear their cases,” she added.

The courts are also working on upgrading the technology used in conflict-screening systems, Elrod told lawmakers. Some judges, when asked to explain their failures to recuse by the Journal, blamed screening failures on spelling errors.

The latest news, as soon as it breaks.

Get our email alerts straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.