Focus: 75 years later, keeping Pearl Harbor memories alive

Wednesday marks the 75th anniversary of the Japanese aerial attack that shoved the United States into World War II. Those who were there have long shared a rallying cry: “Remember Pearl Harbor!”

They worry now that the punctuation at the end of the cry will one day be a question mark.

Remember Pearl Harbor?

Except for Hawaii, where the surprise attack happened — and where more than a week of anniversary events are planned this year — few communities have cared as much as San Diego about keeping the memory of that horrific day vibrant and relevant.

This is a place — maybe the only place — that still has an active local chapter of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association. The national organization disbanded five years ago after its membership, once close to 30,000, fell to less than 3,000. The San Diego group, always one of the largest in the country, shifted under the wing of the nonprofit Veterans Museum in Balboa Park, enabling it to have monthly meetings, collect dues and elect officers.

San Diego is where sons and daughters of the survivors are busy with their own organization, learning the stories so they can pass them on, and safeguarding the family mementos — newspapers, photos, uniforms — that help bring the events to life. This is where the USS Midway Museum holds an annual Pearl Harbor Day ceremony. It’s where memorials to the attack decorate waterfront parks, and also a coffee shop in Tierrasanta and a bedroom in a house in Bonita.

And it’s where the dock landing ship Pearl Harbor is based, the first Navy vessel to be named after the attack. San Diegans helped persuade military brass to swallow their pride and use the moniker. The Navy doesn’t like naming ships after losing battles. But Pearl Harbor over the years has come to represent something more than loss.

“Pearl Harbor wasn’t a defeat,” said Stuart Hedley. “It was an eye-opener.”

He wonders sometimes how much longer those eyes will be open. President of the local survivors group, Hedley turned 95 in October, which means he was 20 that day when the West Virginia, the battleship where he was stationed, got hit by a torpedo and was badly damaged. He still remembers a lot of the details and shares them regularly in talks at schools and in front of civic groups.

“Let me tell you,” he said. “The majority of people today don’t even have the slightest idea what happened there.”

Opening fire

The first shot at Pearl Harbor wasn’t fired by the Japanese.

About 3:45 on the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, a minesweeper called the Condor was on patrol near the harbor’s entrance when a crew member spotted what he thought might be the periscope of an enemy submarine. The call went out: “We got company here.”

Ray Chavez, who lives in Poway and at age 104 is believed to be the oldest living Pearl Harbor survivor, was on board the Condor as a quartermaster in charge of navigation. He remembers how the crew used blinker lights to notify the destroyer Ward, which went looking for the sub but didn’t find anything.

A few hours later, crews on board a supply ship and a patrol plane made additional sightings, and the Ward moved in again, firing shells and dropping depth charges that sunk the sub.

His shift over, Chavez went home to his Navy apartment across the street from Hickam Field and straight to bed. A short time later, as he remembers it, he was awakened by his wife. “We’re being attacked,” she said.

“What do you mean?” Chavez asked.

“The Japanese are attacking us and the harbor is on fire,” she said.

“Oh, go on.”

It was around 8 a.m. Chavez got out of bed and saw for himself. Japanese planes were everywhere, the first wave of a strike force of 350 fighters, torpedo planes and bombers launched from six aircraft carriers that had traveled 12 days across the Pacific Ocean, undetected, to get within striking distance.

They zeroed in on Battleship Row, destroying or damaging 19 U.S. battleships, cruisers, destroyers and auxiliary ships, including the Arizona, which blew up when a bomb crashed through the deck and detonated in a powder magazine. Hedley, who was on the West Virginia docked nearby, remembers seeing dozens of bodies fly through the air.

Fifteen other ships were damaged or destroyed, and the water surrounding them was soon covered in burning oil. Hedley said he dove under the building-high flames toward shore. “I knew how to swim, but not underwater,” Hedley said. “I swam underwater that day.”

Roused on a sleepy Sunday morning, their ammunition locked away in storage sheds, U.S. service members fought back as best they could. At Kaneohe Bay, John Finn wrestled a .50-caliber machine gun onto an instruction stand and fired at the Japanese planes. Hit 21 times by bullets and shrapnel, he refused to leave for medical treatment until he was ordered to do so. Five months later he was awarded the Medal of Honor. Finn retired to San Diego. He died in May 2010 at age 100.

Gordon Jones was also at Kaneohe Bay that day. Now 94 and living in Chula Vista, the former aircraft instrument technician recalled how angry everybody was in the aftermath. “We hadn’t heard anything about any war starting,” he said.

The attack lasted about 75 minutes. It killed 2,400 Americans. A day later, President Franklin D. Roosevelt got Congress’ approval to declare war, famously calling what happened in Hawaii “a date which will live in infamy.”

A nation transformed

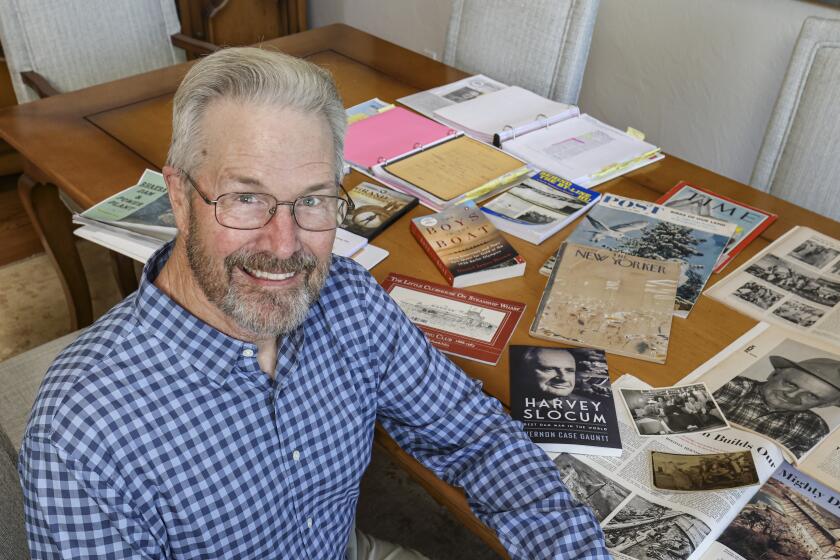

In his new book, “Pearl Harbor: From Infamy to Greatness,” New York writer Craig Nelson argues that the nation we live in today wasn’t born on the Fourth of July, but at Pearl Harbor.

“The attack on American soil galvanized and united a United States torn apart by partisan squabbling and helped Americans to start thinking of themselves as citizens of the country and of the world,” Nelson wrote. “Being forced to wage war on two oceans and three continents meant an end to America’s Great Depression — 1933’s unemployment rate of 24.9 percent became 1942’s rate of 1.2 percent — as well as a transformation of the country from a timid and withholding isolationist into a global superpower.”

Nelson and his research team of a dozen people spent five years combing through almost 1 million pages of documents in New York, Washington, Honolulu and Japan to re-examine the origins of the attack and its far-reaching aftermath.

Voices: Remembering Pearl Harbor »

“The attack was so much more gruesome and horrific than people understand,” Nelson said in a phone interview. “The average age of the men was 19, very young, and they had no idea it was coming. They were firing at Japanese Zeros with 1903 Springfield rifles. One guy chased after the planes on a bicycle. It was even more pathetic than most people know.”

One of the things the researchers examined was archives of oral histories. “There’s almost nothing with any specific detail when the veterans are interviewed in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s,” Nelson said. “They didn’t talk about it. They were traumatized, but PTSD was something you just got over. You got on with your life.”

That changed after the Pearl Harbor survivors started getting together for reunions and then formed local associations. They came to know each other not just by name, but by where they were that morning. It wasn’t Joe Smith; it was Joe Smith from the Oklahoma. In this way, they positioned themselves over and over on the stage of a drama that defined their lives.

When they were together, they could talk about how the Japanese bullets clanged off metal and sizzled through water. What the mixture of burning oil and flesh smelled like. How shocking it was, in the days after, to walk by boxes marked “Body Parts.” And how lucky they felt to have survived.

They became recognizable by their uniforms: Hawaiian shirts and white slacks. And they started going out into the community, to schools and libraries and civic meetings, to share their stories.

“It could easily be said that Pearl Harbor would not today hold the special place it does in American hearts if not for their efforts,” Nelson wrote.

On a recent Monday evening, Hedley drove from his home in Clairemont to the Admiral Baker Golf Course west of Allied Gardens. Inside the clubhouse, he gave a talk to a group of about a dozen active and retired social studies teachers. He talked about seeing the Arizona explode, about finding one of his friends cut in half by a sheet of flying glass, about how he’s come to believe if the leaders of countries want to wage war they should all get in a ring and fight it out themselves and “not send millions of young men to their deaths.”

He said local Pearl Harbor survivors — there are 19 in the chapter now — have collectively given almost 134,000 presentations over the years.

“He’s living history,” said Cheryl Rehome, a teacher at Meadowbrook Middle School in Poway. “I can’t wait for tomorrow so I can go in and talk with my kids about what I’ve learned.”

Matt Hayes, coordinator of history and social studies for the San Diego County Office of Education, said those academic subjects often ask the students to consider questions “about who is a hero and who isn’t. Talking about Pearl Harbor is an opportunity to stop and reflect on what we as Americans value.”

And when there aren’t any survivors left to tell their tales? “That will be a little scary,” said Janet Mulder, a retired Jamul middle school teacher. “How else are we going to learn from our mistakes?”

Phoenix rising

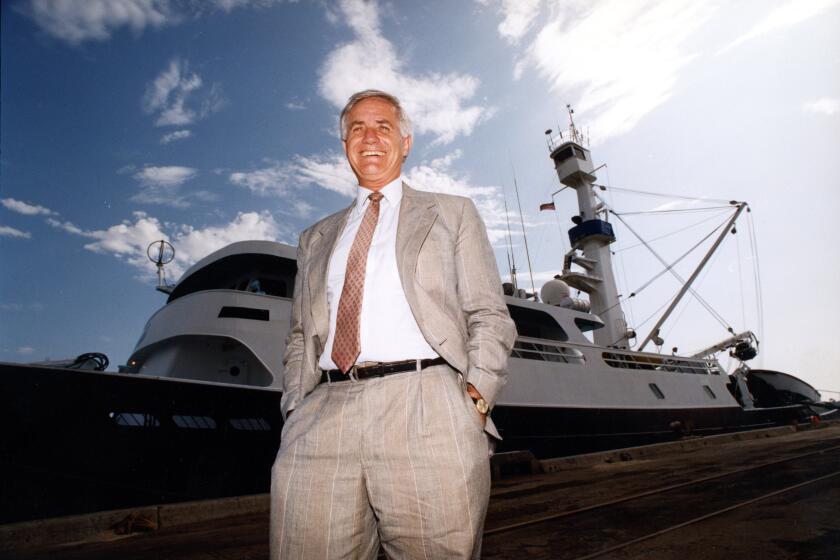

When the Pearl Harbor was put into service on May 30, 1998, about 5,000 people attended the ceremony at North Island Naval Air Station. Among them was Jones, the retired Kaneohe Bay aircraft instrument technician.

He and other local Pearl Harbor survivors had spent 15 years trying to persuade the Navy to name a ship after the attack. Jones wrote more than 60 letters. The reply was always the same: “We have more names than we do ships, but we will consider you in the future.”

Between the lines, what the survivors read is that the Navy wasn’t interested in naming anything after the military disaster. To the survivors, though, remembering it was the whole point. How else could the nation avoid a bloody repeat? “Remember Pearl Harbor” was only half of the association’s motto. The other half: “Keep America Alert.”

After the survivors won the argument and the 610-foot-long dock landing ship was stationed in San Diego, Jones often showed up pier-side to wave goodbye when it left on deployments, and to wave hello when it returned. “Hey, Jonesy!” crew members shouted at him. He waved back. He once went as a guest on the ship when it sailed back from Hawaii.

Ask Jones about all that now, and his brow furrows. “I did that?” Like many of the survivors, his memory isn’t what it used to be.

But the connection between the ship and the men, between the ship and what happened 75 years ago, remains strong. There’s a silver service on board from the Raleigh, a cruiser that was hit with a Japanese torpedo and a bomb during the attack but suffered no loss of life. The ship’s anti-aircraft batteries were credited with shooting down five Japanese planes.

That’s just one of several Pearl Harbor artifacts on board the ship, said Cmdr. Ted Essenfeld. He acknowledged the awkwardness of having a ship named after a losing battle, but the crew has embraced the larger message. On baseball hats for the Pearl Harbor is an image of a Phoenix rising.

On a recent Sunday morning, Essenfeld — the ship’s commanding officer — put on his uniform and went to the Good Samaritan retirement center in El Cajon with his wife and two sons. In a basement meeting room, the local Pearl Harbor survivors chapter was having its annual installation of officers. Essenfeld was there to swear them in.

“We on the ship consider them our greatest treasure,” he said.

About 30 people attended, including five survivors. They approved the minutes and listened to a financial report. There was a moment on the agenda for Essenfeld to say something about the outgoing president, but the outgoing president was the same as the incoming one: Hedley. No one else is up to the job.

In addition to the 19 actual survivors, the local association includes spouses, sons and daughters, and honorary members — 117 in all. At its peak, the chapter had about three times that number.

Hedley said he doesn’t know how much longer the group will last. “All the survivors are passing away, and in another 75 years, all the sons and daughters will be gone, too,” he said.

For now, though, memories linger. Which is why on Wednesday, when the Pearl Harbor is at sea, the 75th anniversary will be observed on board with a moment of silence.

‘It’s an honor’

At least six local Pearl Harbor survivors are planning to go to Hawaii for the commemoration ceremonies, which started Thursday. A couple dozen “sons and daughters” and other relatives from San Diego are going, too, along with civilian survivors.

The emotional high point of the trip figures to be Wednesday morning at Kilo Pier for a “Remembrance Day” event that begins at 7:45 a.m., around the time Japanese planes began strafing and bombing the island. There will be speeches and music. The survivors, many of them in wheelchairs, will be front and center.

This figures to be the last major gathering for many of them, but people have been saying that for at least 25 years, and the former servicemen always seem to rally themselves, just as they did on that Sunday morning so many years ago.

“It means a lot to me to be there because I was part of the men who were lost,” said Chavez, the minesweeper quartermaster. “The only difference is I lived and they died. It makes me feel like I’m seeing old friends. It’s an honor.”

Chavez is traveling with his daughter, Kathleen. “I think a lot of people still remember Pearl Harbor,” she said, “but what I don’t think they realize is that without my father’s generation and what they did, we would be living in a totally different world.”

Pat Thompson’s world has come full circle. The daughter of a Navy radioman, she was 10 and living at Pearl Harbor when it was attacked. She heard the planes and went outside and waved. “I thought they were ours,” she said.

The night before, she had gone to a dance and done the jitterbug with a 17-year-old sailor from the Tennessee — done it so well that they won that night’s contest. Her afterglow disappeared quickly amid the chaos and alarm.

A few decades passed and Thompson made her way to San Diego and public relations work for the Chargers. She never stopped wondering what had happened to her jitterbug partner. She checked Navy archives for any word about the dance. She asked veterans’ groups to put articles in their newsletters.

One day she got a phone call. “I’m the sailor you’re looking for,” Jack Evans told her. Turns out he lived in Chula Vista, just 15 miles from her home.

During the commemoration for the 60th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, they danced again. Five years later, same thing.

So there are lots of ways to keep history alive, Thompson said. She donated her jitterbug trophy to the USS Arizona Memorial. And at the Pearl Harbor Visitor Center, in the museum, there’s a photo of her 10-year-old self on a wall alongside pictures of other people who were living on Oahu in 1941, before their world — before the whole world — changed forever.

Related:

• Pacific Beach man’s Pearl Harbor mission of reconciliation

• Oldest Pearl Harbor vet still pumping iron at 104

• Pearl Harbor: In a stunned heartbeat, my family moved to San Diego

• Internee has different memories of war

Pearl Harbor 75th anniversary

Pearl Harbor survivors relive the infamous day

12:34

104 years young

Aircraft Warning Service Volunteer recounts her experience in after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor

2:40

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.