5 things you should know about antibodies during the pandemic

A quick rundown of what antibodies can (and can’t) tell us about COVID-19

As scientists and doctors scramble to track the scope and severity of COVID-19, antibodies have become something of a buzzword.

Here are five things you need to know about coronavirus antibodies, including how and why scientists — many of them in San Diego — are studying them, and why some think they might be the key to reopening the economy.

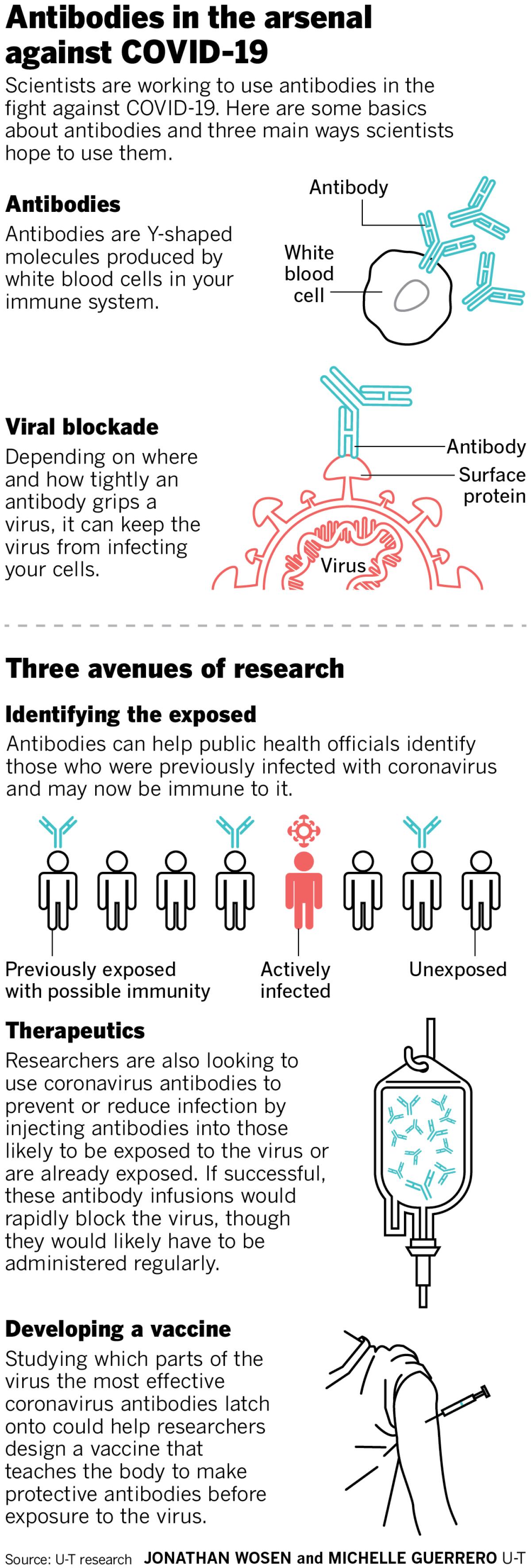

What are antibodies?

Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins made by your immune system in response to an infection. These molecules latch onto viruses or bacteria, and if they grip tightly enough at just the right spot, block the pathogen from infecting your cells. Microbes coated in an antibody are also more likely to be gobbled up and destroyed by immune cells — a bit like how you might prefer food that’s been flavored. The term for this process, opsonization, literally comes from the Greek word for seasoning.

What are these coronavirus antibody tests that keep popping up? Are they different from viral tests?

The antibody tests you’re hearing about (and there are a lot of them) screen blood samples for antibodies that stick to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Viral tests use nose and throat swabs to detect the virus’s genetic material directly.

Those swabs reveal whether someone has the virus now, but not whether they were infected weeks or months ago. Without this information, public health officials don’t know how many people have been infected — which is why we also don’t know the true death rate of COVID-19 or how many people might now be immune.

“It can really help you if you’re trying to answer a question like how many people are asymptomatic,” said Dr. Robert “Chip” Schooley, a UC San Diego infectious disease specialist and editor of the medical journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. “When you use antibody tests with large numbers of people, you can see who has the antibodies but never had symptoms, and you can begin to paint a picture of how common it is.”

To help get these answers more quickly, the Food and Drug Administration announced on March 16 that it would allow companies to develop antibody tests without going through FDA review. By April 7, more than 70 developers sprang forward with tests.

One of them is Diazyme, the San Diego life sciences affiliate of General Atomics, located in Poway. Since its test became available on March 23, the company has produced about a half-million tests, according to managing director Chong Yuan, who says that Diazyme is preparing to produce that many tests each week. Those tests have been distributed nationwide, including to labs at UC San Diego Medical Center, and soon, he says, to Scripps Research Institute.

These tests detect antibodies that appear early in the immune response and those that emerge later — which could indicate how recently a person was infected. But the absence of antibodies doesn’t mean that a person doesn’t have the virus, as it can take antibodies days or weeks to appear.

“It’s not used as a sole diagnostic tool,” Yuan said. “Eventually, you still have to finally confirm with molecular tests” that measure the virus directly with a nose or throat swab.

Even though the FDA is allowing antibody tests to be used without formal approval, these tests still have to be performed by certified labs. That’s why one pop-up testing center at MiraCosta College’s San Elijo campus was shut down by the county on Wednesday.

If antibodies can block the virus, can they be used to treat people?

Potentially. Researchers are actively testing this. Administering antibodies to those at high risk of coronavirus exposure — such as health care workers in urgent care settings — might potentially prevent them from getting infected. And antibodies could slow the virus in those who’ve already been infected.

Antibodies are already used to protect high-risk infants against the respiratory syncytial virus, another airway pathogen, but they’ll have to prove their worth against COVID-19. Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, a biotech based in Tarrytown, New York, is screening hundreds of coronavirus antibodies in search of a couple of promising therapeutic candidates for trials set to begin by early summer.

Locally, La Jolla Institute’s Erica Ollmann Saphire is leading an international team of researchers searching for protective SARS-CoV-2 antibodies. The key to these efforts is not simply finding antibodies that latch onto the virus, but that do so in the precise spots the virus uses to invade a host cell. Such antibodies could then be produced in bulk in the same way as antibodies used to treat cancer and autoimmunity.

How would antibody treatments differ from a vaccine?

Even if researchers find antibodies that prevent or treat COVID-19, antibody treatments would be pricey and likely need to be administered regularly, says Dennis Burton, an immunologist at Scripps Research Institute.

“That’s a relatively expensive way to treat or prevent disease,” especially in the developing world, Burton said. “The favored, cheapest and most effective long-term way to do it is through a vaccine.”

Any COVID-19 vaccine — including the efforts of Inovio and Arcturus — will take at least 12 to 18 months to go through rigorous testing for safety and efficacy. But the upside is that a vaccine would teach the body to produce protective antibodies on its own.

Studying antibodies from the blood of those who’ve recovered from the disease might teach scientists how to do that. That’s why Burton’s lab is carefully studying antibodies from the blood of COVID-19 survivors.

“We’re trying to understand what’s happening with all these antibodies that are being made — the ones that are working, and the ones that are not,” Burton said. “Can this teach us about the qualities we should have in a vaccine?”

Can antibodies help get us back to work and out of our homes?

If antibody responses protect against future infection, and if that protection is long-lasting, then yes. But scientists don’t yet know if that’s true.

“We don’t know if the presence of those antibodies means you’re immune or not,” said Burton, whose lab has spent years studying HIV antibodies — most of which don’t offer much protection against the virus.

Some antibody responses last for decades, as is the case for tetanus, but researchers don’t yet know how long SARS-CoV-2 antibodies last. And early results from Burton’s lab suggest that a small fraction of people who’ve recovered from the virus don’t have strong antibody responses at all — a puzzling finding.

“If that’s the case, then that might confuse matters with regards to immunity,” said Burton, who cautions that his lab is looking into the matter further.

Clearing up that confusion will be critical, as the more people who have protective antibodies to the virus, and the longer those antibodies last, the sooner officials can safely roll back stay-at-home orders.

U-T staff writer Paul Sisson contributed to this report.

Get U-T Business in your inbox on Mondays

Get ready for your week with the week’s top business stories from San Diego and California, in your inbox Monday mornings.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.