WASHINGTON — With the Electoral College tallies last week, the 2020 presidential race is finally over, but Democrats and Republicans continue to argue about the results. And one debate in particular lingers: Did President-elect Joe Biden win by a little or by a lot?

The answer is ... yes, depending on how you measure the votes. And closer looks at this year's election and past races show why the Electoral College/popular vote divide is increasingly worrying in a sharply divided nation.

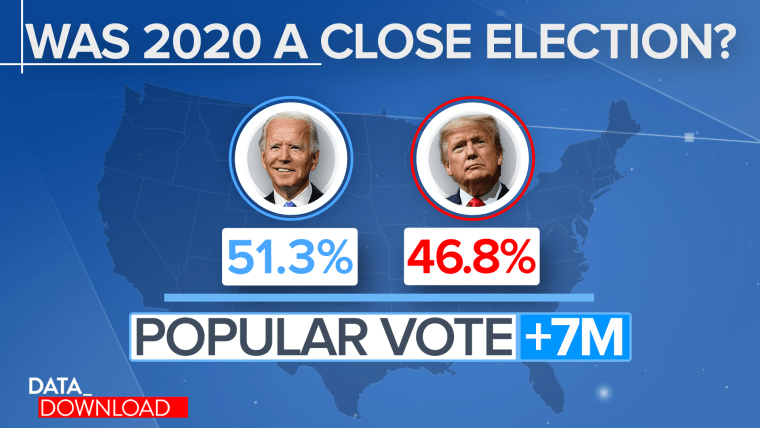

Let's start with 2020. Looking at the popular vote, Biden won by a sizable margin.

Biden's 4.5-point victory margin is the second largest since 2000. Only Barack Obama's 7-point win in 2008 was bigger. The same is true of Biden's margin of 7 million popular votes. Obama won by 10 million in 2008. And, of course, the 81 million votes Biden won is by far the most any presidential candidate has ever received.

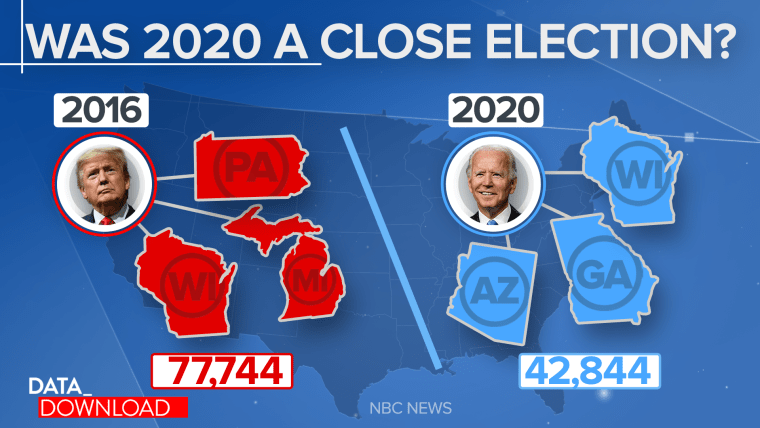

But if you look just at the states that put Biden over the top in the Electoral College, he won by fewer votes than Trump did in 2016.

Throughout Trump's time in the White House, much has been made of how he won the presidency by under 78,000 votes in three states. And that point was true. Trump won because of narrow margins in Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

But the margins this year were even tighter in the three states that put Biden over the top in the Electoral College. He won Arizona, Georgia and Wisconsin by a total of less than 45,000 votes.

The difference between the popular and Electoral College votes has gotten a lot of attention lately. Democrats are usually more than happy to point out that Republican candidates have won the popular vote exactly once since 1992, when George W. Bush won it in 2004. But the bigger concern is that the popular/electoral divide is growing.

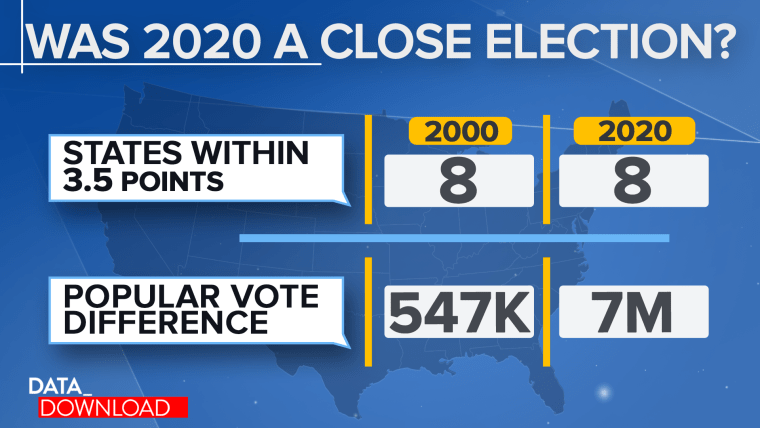

Consider the 2000 election. That race that is well-remembered for coming down to a recount in Florida, but even outside Florida, the election was extremely close. The overall national difference in popular votes was 547,000, or just half a percentage point. And there were eight states where the winning candidate's margin was less than 3.5 percentage points.

Now compare that to this year. Biden won the popular vote by 7 million votes and more than 4 percentage points, but there were still eight states where the winning candidate's margin was within 3.5 points.

In other words, a swing of a few thousand votes in a few states this year and the country could have been looking at a second term for Trump, even though Biden would have won the national popular vote by 7 million votes. In a country where political divisions have grown more intense, that kind of divide between the popular and the institutional winners would be deeply problematic.

Does that mean the Electoral College may be on the way out? Don't bet on it.

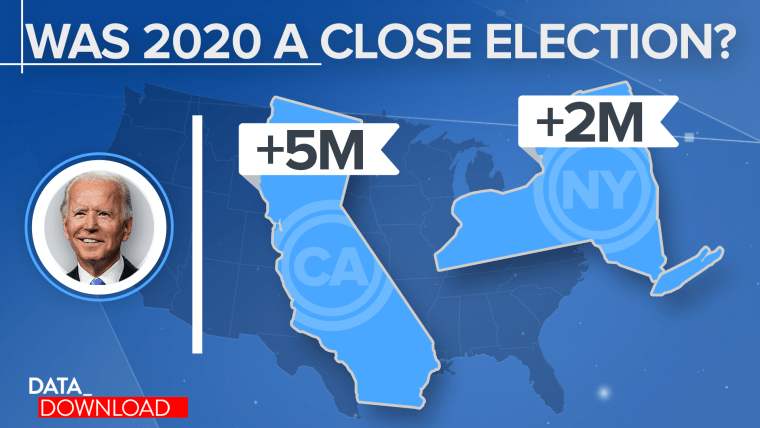

Remember that point about the Republican presidential candidate's winning the popular vote only once since 1992. And then add this data point about 2020: Biden's national popular vote margin, that 7 million-vote edge, comes from just two states: California and New York. That's not a political reality Republicans are eager to inhabit.

So for now, the popular/electoral gap seems set to grow, driven in part by an urban/rural split among voters. It means that neither the Democrats nor the Republicans are likely to capture a mandate that would allow them to do what they want in a country that says it is hungry for change.

With a new year and a new president arriving soon, that seems to leave Washington with one meaningful, worthwhile resolution for next year: a more bipartisan 2021.

Easy? No. But the holidays are a time to dream.