The long lines of people waiting for food at the country’s food banks is an enduring image of the pandemic’s impact on American families. All over the United States, people were turning to food pantries to help feed themselves and their families, stretching a system that has been in place for decades. The system had to reinvent itself almost overnight to make sure they met the need and to keep their customers and volunteers safe from COVID-19.

You may recall seeing the staggering number of cars waiting at drive-thru food distribution centers in cities like San Antonio and Minneapolis. That need was also felt locally in cities like Missoula, where the Missoula Food Bank & Community Center went from helping 8,723 new customers in 2019 to 21,626 in 2020. That increase was just in new clients. The total number of individuals and families was even higher reaching 32,422 individuals and 11,317 households.

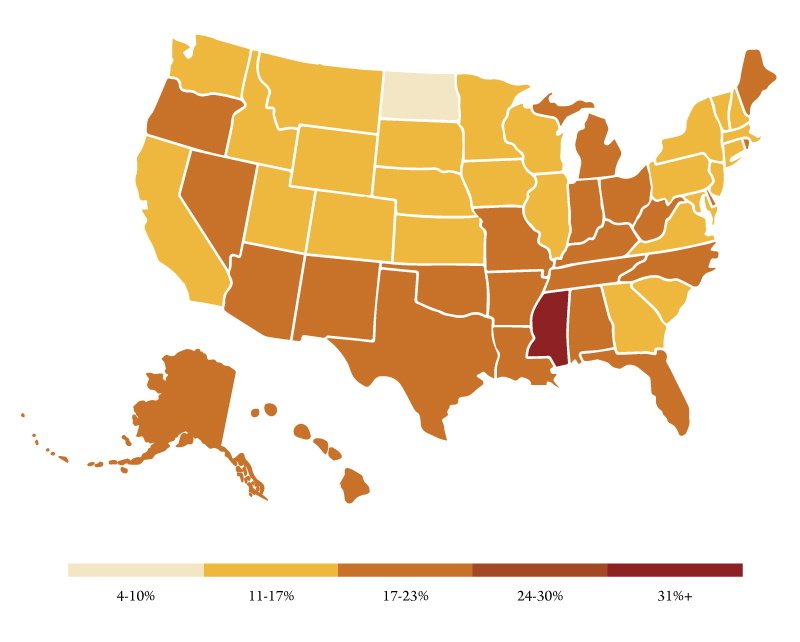

Over the past five years, the percentage of households experiencing food insecurity was trending slightly down from 12.6% in 2015 to 10.54% in 2019. However, it is estimated that the pandemic will increase that to 23%. A significant number of people fell into poverty and food insecurity as a result of the nationwide lockdown. Workers who were furloughed or lost their jobs, and parents who had to stay home with their children and couldn’t work full-time had to turn to their local food pantries.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, April 2020 saw the national unemployment rate jump to 14.7%. In Montana, that same month the unemployment rate peaked at 11.9%. Hardest hit of any group nationally, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, were Native Americans with an unemployment rate of 26.3%. Across the state on Montana’s Indian reservations, the unemployment rate ranged from 10.3% on the Flathead Reservation to 22.8% on the Rocky Boy Reservation.

COVID-19 and Food Distribution Challenges

This rapid rise in need created an extraordinary challenge for organizations distributing food. Almost overnight, food banks and pantries had to retool their distribution systems to avoid direct contact with their customers. The Missoula Food Bank & Community Center planned for this drastic change over a weekend in March 2020. Their model had formerly been replicating a grocery store experience where clients shopped along the aisles. To streamline the process the food bank simplified the intake system by creating a grab-and-go method of giving food in pre-filled grocery carts.

But the community center had to shut down, foregoing an integral part of what the food bank used to be – a public gathering place, the one-on-one conversations to provide information about accessing resources, and children playing and eating in the family rooms.

In Denver, the local food pantry, Joy’s Kitchen, had to totally revamp their distribution system. Before the pandemic their food distribution system was decentralized with volunteers loading up perishable and nonperishable goods to multiple sites around the city. But that was turned upside down as sites closed. They centralized their operations to one location, a church, which remained open for food storage and for volunteers to assemble food packages, which were handed out to families in their cars. Shifting from multiple distribution sites to one site created enormous challenges, but 4,000 families per month were served in 2020.

Food bank and pantry staff around the country were reduced to skeleton on-site crews, with administrative staff working from home. Food pick-up was moved to curbside or a walk-through area with volunteers and staff delivering food baskets directly to clients. Even with limited exposure, if one volunteer or staff member tested positive for COVID-19, the whole crew had to be quarantined and a standby crew called in. For instance, the Missoula Food Bank & Community Center severely reduced their number of volunteers from 9,005 providing 50,974 volunteer hours to 1,513 providing 23,817 hours of work.

Although food banks and pantries operate very much like any food distribution system, the pandemic presented challenges to nonprofits having to adapt to the growing demand. Limited warehouse space and financial constraints pushed many beyond their processing and packaging limits. Each individual operation had to adapt quickly to the changes created by initial disruptions in the national supply chain, which further exacerbated problems.

Food rescue or food recovery is a source of goods used by many nonprofits. It involves the organization picking up or having delivered edible food that would otherwise go to waste from places such as restaurants, grocery stores, produce markets or dining facilities. For example, Food Rescue US, a national nonprofit established in 2011, has since provided 68 million meals and kept 89 million pounds of excess food out of landfills. Food recovery is one of the major ways these nonprofits acquire food to redistribute. The pandemic turned this important source of product on its head. Businesses and institutions that once donated food were no longer operating, and grocery stores were no longer dealing with too much food on the shelves, but rather too little. Some food banks and shelters resorted to buying food that remained on store shelves.

But Americans responded generously to the crisis. Individual giving increased and there was an outpouring of donations to local food banks. Highly publicized donations came from Amazon founder Jeff Bezos, who gave $100 million to Feeding America, the largest national network distributing food to people in need. The Missoula Food Bank & Community Center reported an outpouring of individual donations too, which helped them purchase food when donations slowed from grocery stores and local food drives.

The Government Response to Food Insecurity

The federal government has passed a number of COVID-19 relief packages. So far, lawmakers have enacted six major bills, costing about $5.3 trillion, to help manage the pandemic and mitigate the economic burden on families and businesses. Just over $9 million came into Montana for a number of qualifying uses. Three of these stimulus packages included direct payments to individuals for a possible total of $3,200 per individual and $1,500 per child. Montanans received approximately $1,400 per capita in these three rounds of stimulus payments.

The majority of recipients spent their stimulus checks on basic needs or used it to pay off debt. However, lower income households were more likely to spend their stimulus checks just to meet basic needs. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 33% of adults said they used the second stimulus check to pay for food. The Missoula Food Bank & Community Center reported an immediate decline in people seeking food in the days directly after they received their stimulus checks.

An increase in unemployment benefits had a greater impact on struggling households. The increase in state unemployment payments provided in the federal COVID-relief packages ranged from $600 per week to $300 per week. The aid was also extended to workers who usually do not qualify for unemployment benefits, including gig economy workers and independent contractors. One-third of adults reported using both stimulus payments and enhanced unemployment benefits to cover normal household expenses.

Other federal responses included an increase in Supplement Nutrition Assistance Program benefits. The increases from the federal unemployment boost did not count toward a person’s income when they applied for SNAP, which made it easier to qualify for the benefits.

The CARES Act also earmarked millions of dollars to support food banks and programs such as Meals on Wheels. More recently, money has been earmarked to expand the reach of the Community Supplemental Food Program to more low-income seniors and provide additional support to the states and tribes that administer the program.

What the Future May Hold

While the government response and an increase in charity helped feed many families and kept food distribution centers open, there are lessons to be learned that may help inform our future responses to crises.

The pandemic exposed flaws in the food distribution systems at all levels of the supply chain: food rotting in fields, food laborers unable to work, panic buying, collapsed transportation systems and processing plants closing or being overwhelmed. Normally, feeding people who experience food insecurity comes from the surplus of food waste left by those with the means to access it. This would erroneously appear to be a win-win situation, but it is a system built on the existing inequities within America. As inequity increases and more people need food, more surplus food is needed, creating an unsustainable situation.

There have been some creative responses to address these issues, such as food sharing and community transport systems, which give local food rescue networks an opportunity to develop a more sustainable community food system. Also, direct farm-to-food-bank purchasing agreements that can be expanded to support local agriculture.

Despite the federal infusion of trillions of dollars, it has done little to stem the rise in poverty and inequality that existed before the pandemic. According to a Brookings Report, the pandemic disproportionately impacted the same disenfranchised groups. Workers with less education, who could not easily shift to working at home; young people, reflecting lower levels of education and high representation in service industries; females who bore the majority of child care responsibilities when schools closed; and African American, Hispanic, Native American and Asian American workers.

Food insecurity is directly related to poverty. Meeting immediate needs through distributing excess food through food banks and pantries has become increasingly sophisticated and well-established, what some call the “hunger industry.” The pandemic has raised awareness of a U.S. food insecurity crisis and exposed some cracks in the existing system. Until policymakers address the underlying American inequality, getting food to people must be a priority, especially during the economic upheavals like the COVID-19 pandemic.