Must Reads: Orange County goes blue, as Democrats complete historic sweep of its seven congressional seats

Gil Cisneros defeated Republican Young Kim on Saturday in the last of Orange County’s undecided House races, giving Democrats a clean sweep of the state’s six most fiercely fought congressional contests and marking an epochal shift in a region long synonymous with political conservatism.

With Cisneros’ victory, Democrats will constitute the entirety of Orange County’s seven-member congressional delegation, the first time since the 1930s that the birthplace of Richard Nixon, home of John Wayne and spiritual center of the Republican Party will have no GOP representative in the House.

“Sitting back in the 1960s, I would never have believed this would happen,” said Stuart K. Spencer, a party strategist who spent more than half a century ushering Republicans, including President Reagan, into office.

But noting the extensive demographic and political changes that have taken place — especially over the last two decades — “it’s pretty understandable,” Spencer said.

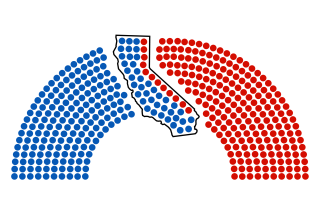

Cisneros’ victory, after more than a week of counting mail-in and other outstanding ballots, will give Democrats 45 of the state’s 53 House seats and mark a new low for the flailing Republican Party, which dominated the state and its politics for much of California’s history.

The result also caps a highly successful Democratic midterm election. The loss of the GOP’s last four Orange County seats and two more farther north raises to 38 the number Democrats have gained nationwide, more than enough to seize control of the House when lawmakers are sworn into office in January.

The Democratic takeover was not unexpected, coming at a time of sagging approval ratings for President Trump and fervent energy on the political left.

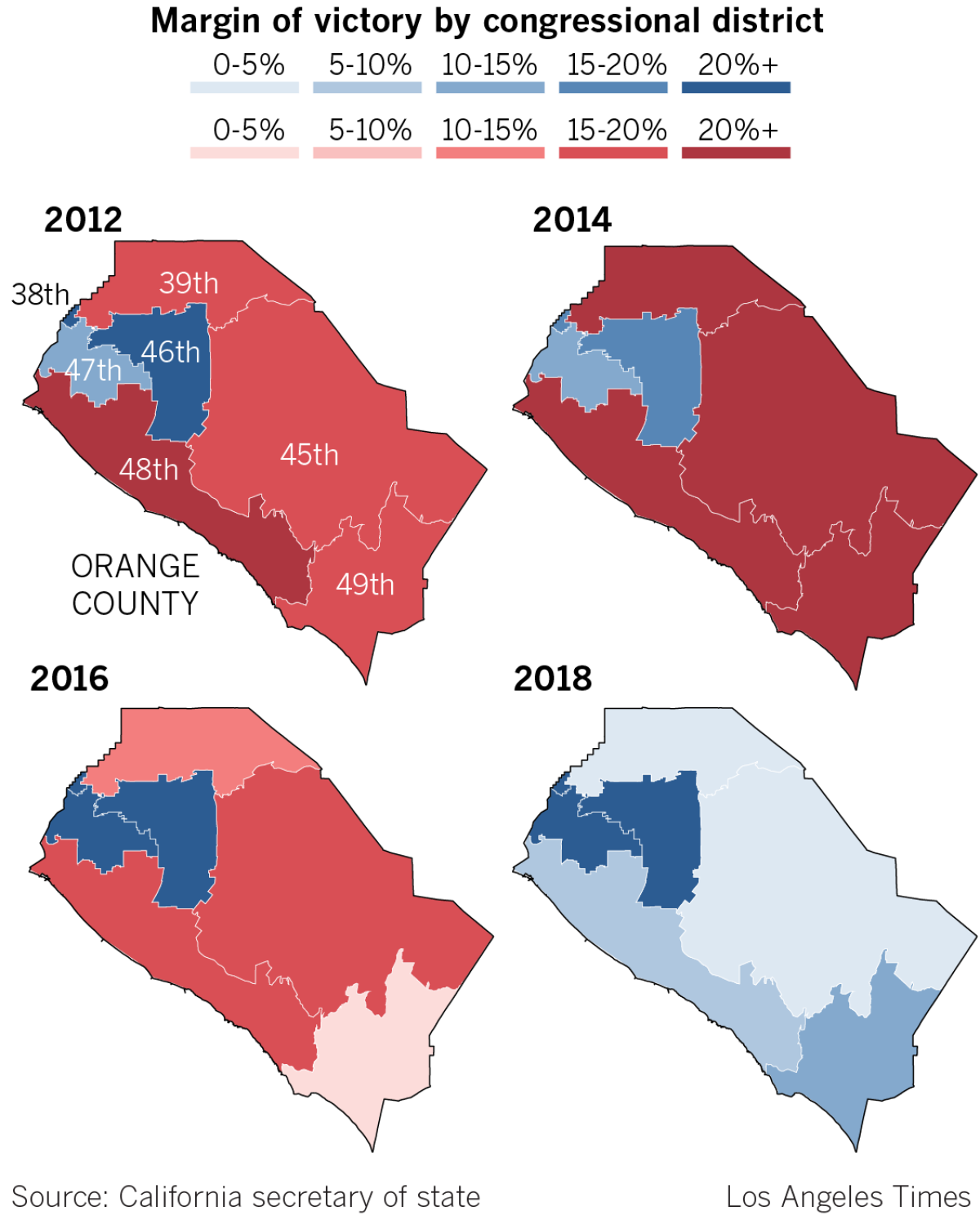

It’s the Republican wipeout in Orange County, a wellspring of conservatism that nourished generations of state and national party leaders, that stands as a shock. Many never thought they would see a day when its expansive suburban tracts were anything but flaming Republican red.

“A huge deal,” said Eileen Padberg, a veteran GOP strategist who recently shed her affiliation out of frustration with Trump and the national party.

Likening the GOP’s hegemony to a dictatorship, Padberg said that for as long as she could recall, “If you wanted contracts, if you wanted a job, you had to be a Republican.”

But, she said, as Orange County changed — growing younger, more diverse, more socially tolerant — most of its Republican lawmakers failed to change with it. “They focused only on their right-wing base,” Padberg said, “and didn’t do a good job problem-solving.”

Trump, who lost Orange County to Hillary Clinton in 2016, was no help, weighing down Republican incumbents and challengers alike.

Kim was typical. Although the former state lawmaker offered an attractive political profile as a Korean American immigrant in a heavily Asian American district, she was never able to shed — though she tried — her attachment to Trump, his pugnacious persona and divisive policies.

Cisneros, a Navy veteran and lottery winner who invested a chunk of his fortune in the campaign, will succeed retiring 12-term Republican Rep. Ed Royce in the 39th Congressional District, which straddles Orange, San Bernardino and Los Angeles counties.

Democrats also ousted Mimi Walters, a two-term Republican who lost in inland Orange County to Katie Porter, and 15-term Republican Dana Rohrabacher, who lost his coastal Orange County seat to Harley Rouda.

Democrat Mike Levin will replace retiring nine-term GOP Rep. Darrell Issa in the seat along the southern Orange and northern San Diego county coasts. Democrats also picked up the seats of two-term incumbent Steve Knight, who lost to Katie Hill, on the northern outskirts of Los Angeles, and Republican Jeff Denham, who surrendered his San Joaquin Valley seat after four terms to Josh Harder.

In a state unaccustomed to competitive congressional races, the contests were a (not always welcome) revelation. In the four tightly contested Orange County races alone, the spending topped $130 million; voters were bombarded with scathing TV ads and a ceaseless barrage of phone calls, text messages and doorknockers.

Democrats outspent Republicans by a wide margin, warning of cuts to Medicare and Social Security and pounding GOP incumbents for voting to repeal the Affordable Care Act. The Democrats also hammered Republicans for siding with Trump on his tax overhaul, which threatens to hurt many Orange County residents by limiting federal deductions for state and local taxes.

“In the cradle of the Reagan Tax Revolt, Democrats flipped the script on Republicans,” Drew Godinich, a strategist with the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, wrote in an after-election report.

The committee played an important role in helping to turn Orange County blue. Staffers took up residence starting last year, and strategists helped cull the crowd of Democrats in some races and locked down Issa’s district early by targeting the strongest GOP candidate and elbowing him aside in the June primary.

For Republicans in Orange County, the decline happened slowly, then all at once.

The right-wing conservatism that the nation would come to know emerged after World War II, as small farming communities boomed, with families working at new military bases and aerospace firms. Those residents — many part of the white flight from Los Angeles County, others from the Midwest and the South — were naturally conservative Cold Warriors, whether they were Republican or Dixie Democrats.

Most owned homes and resented high taxes. They were Christians whose social circles often revolved around church. And they wanted none of the cultural and racial foment that was developing in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

They were mobilized by virulently anti-communist rhetoric at rallies, in church, school and John Birch Society meetings, and by the county’s daily newspaper, the Register, which saw as many communist plots to take over America and brainwash its citizens as Birchers did.

So while Orange County was in many ways the vision of bland suburban calm, its voters sent fiery right-wing politicians to Washington and Sacramento. And their sometimes outlandish, often bigoted statements — from Reps. James Utt in the 1960s to Bob Dornan in the 1980s — gave the county a reputation for political eccentricity.

Eventually the enticements that drew white newcomers at midcentury — good schools, safe neighborhoods — began to attract people with roots all over the world. Vietnamese refugees settled in Westminster and Garden Grove. Chinese and Iranian families moved to Irvine. Koreans took up in Buena Park, Fullerton, Garden Grove and Irvine.

A building boom in south Orange County brought in thousands of blue-collar Latinos to work construction and service jobs and lured middle-class Latinos into northern parts of the county.

The result was a backlash, manifested most notably in the 1994 passage of Proposition 187, which sought to bar illegal immigrants from schools, hospitals and other government services before it was struck down in court. Tellingly, the statewide initiative was hatched by Huntington Beach resident Barbara Coe, with help from her congressman, Rohrabacher.

He didn’t have to worry about the subsequent empowerment of Latinos, fired by outrage over the controversial measure; his seat was still safely white and Republican. But his neighboring congressman, Dornan, did. In a fierce 1996 contest, Dornan lost his increasingly Latino and Democratic district to Loretta Sanchez, an upset seen as a significant rip in the so-called Republican “Orange Curtain.”

At the same time, as the high-tech sector boomed, the county began drawing more highly educated people from across the country, who brought their Democratic leanings along with them.

“The employees living in Irvine changed,” said Councilwoman Melissa Fox, who first moved to the city in 1984. “If you’re pulling people from MIT as opposed to Alabama, you’re pulling from a less-conservative population.”

There are still areas where hard-right politics can be mainstream, in cities like Yorba Linda — Nixon’s birthplace — San Clemente and Mission Viejo. But dislike for Trump hastened the rising countywide Democratic tide, and party strategists seized the moment.

“If Hillary Clinton would have won in 2016, these seats would still be Republican,” said UC Irvine politics professor Matthew Beckmann, noting the virtual certainty of the party in the White House losing seats in a president’s first midterm election.

Which raises a question: Will Orange County stay Democratic blue, or at least a more competitive shade of purple?

“It’s going to take a couple more election cycles before we know,” Spencer, the longtime GOP strategist, said. “But it’s a sign to me that things are going south for Republicans and if they don’t change the way they do things, they’re going to go even further south.”

Either way, he said, “This election is one hell of a wake-up call for the Republican Party in California.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.