California’s Central Valley overwhelmed by COVID-19 Delta surge

Hospitals in California’s Central Valley have been increasingly overwhelmed by the fourth surge of the COVID-19 pandemic, with officials scrambling to transfer some critically ill patients more than 100 miles away because local intensive care units are full.

The San Joaquin Valley, the Sacramento area and rural Northern California are now the regions of the state being hit the hardest by COVID-19 hospitalizations on a per capita basis, according to a Los Angeles Times analysis. The regions have lower vaccination rates than in the highly populated, coastal areas of Southern California and the San Francisco Bay Area.

“Our system is still paralyzed and is at a standstill, as we’re trying to move a huge number of patients through this healthcare system that is completely overwhelmed,” Dan Lynch, who oversees emergency medical services for Fresno, Kings, Madera and Tulare counties, said at a recent media briefing.

The worst may not be over. According to COVID-19 computer models published by the state Department of Public Health, the number of ICU patients in the San Joaquin Valley is expected to increase well into the rest of September, and hundreds more people could be dead by the end of the month.

“My heart just breaks looking at these projections,” Dr. Rais Vohra, Fresno County’s interim health officer, said at a recent briefing. The predictions equate to “kids that are going to have to go to their parents’ funerals.”

In the San Joaquin Valley, the number of monthly COVID-19 deaths has tripled, from 93 in July to 311 in August. Just in the first six days of September, 78 additional deaths were reported.

The San Joaquin Valley still has an effective transmission rate of the coronavirus above 1, according to the state Department of Public Health, meaning for every person infected, the virus is being transmitted to slightly more than one other person, so the spread of the virus is increasing.

In recent weeks, officials throughout the Central Valley, which produces one-quarter of the nation’s food, have sounded the alarm on the toll of the pandemic. The Sacramento region has seen COVID-19 hospitalizations this summer approach levels seen during its winter surge; by contrast, Southern California’s peak COVID-19 hospitalizations over the summer haven’t exceeded 30% of its winter surge.

Fresno County reported 401 COVID-19 patients in its hospitals Monday, or 41 hospitalized patients for every 100,000 residents. That’s more than double California’s overall COVID-19 hospitalization rate, which is reporting 20 patients per 100,000 residents, and triple the rate in L.A. County, which has a rate of 14 hospitalizations per 100,000 residents.

Even that number belies the true burden on Fresno County’s hospitals, which are also serving many non-COVID patients, Vohra said.

There are “very sick patients taking up every ICU resource, and every bed that’s available, with lots of stress and strain on the entire healthcare system,” Vohra said.

Fresno County is the most populous in the San Joaquin Valley, and valleywide, available intensive care unit beds has been below 10%, forcing the state to order surge protocols. As of Monday, only 8.4% of staffed adult ICU beds were available in the San Joaquin Valley — the seventh-straight day that share has been below 10%, state data show.

After three days below that threshold, state health officials last week activated COVID-19 hospital surge protocols aimed at alleviating the strain on healthcare facilities. Under those protocols, general acute care hospitals have to accept transfer patients if directed — provided they have the room and doing so is considered “clinically appropriate” — and facilities outside the region also must be prepared to accept transfers, should conditions warrant.

Demand is so intense at hospitals that ambulances have been instructed to not transport patients unless they meet criteria sufficient to warrant them being taken to a hospital — the kind of step L.A. County was forced to take during its winter surge.

“This is unprecedented in our area,” Lynch said.

Fresno County has also been forced to transfer severely ill patients far out of the region — as far away as Watsonville in Santa Cruz County, a 140-mile drive from Fresno.

And there is such a demand for coronavirus testing that Fresno County has run out of rapid tests, meaning that instead of people being able to learn whether they may be infected within minutes, they may have to wait 24 to 72 hours for test results.

Fresno County is also suffering a nursing shortage. But there are few nurses to spare. Even Los Angeles County’s public hospital system is unable to staff all of its beds due to shortages.

Officials in Fresno County are trying to recruit traveling nurses, but they’re in such high demand they can command as much as $200 to $250 an hour, and sometimes they’ll leave hospitals in Fresno County after a day of working because they’ve received a better offer somewhere else, Lynch said.

Fresno County officials say federal and state authorities have so far been unable to provide much staffing help. U.S. Defense Department medical staff helped relieve Fresno County in the winter but are not available now, Lynch said. State officials have also said they have limited ability to send staff, Lynch said.

“The clear message is that our valley, our hospital, our local area really needs to make decisions because we’re on our own to take care of this,” Lynch said.

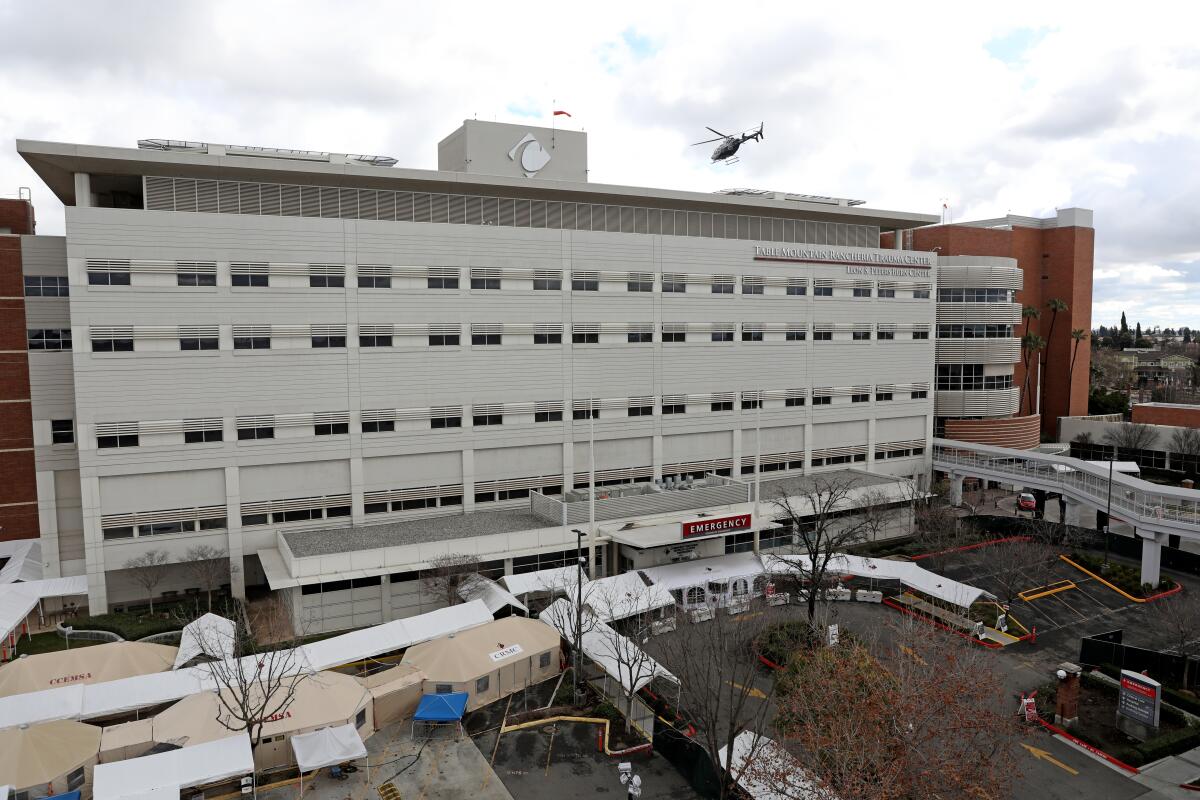

Dr. Thomas Utecht, chief medical officer for Community Medical Centers, which operates four hospitals in the Fresno area, said at a recent briefing that staff have been forced to treat patients in conference rooms and other areas not designed for COVID-19 patients.

“We’re functioning really in a disaster mode at this point,” Utecht said recently. It’s now difficult for hospitals to treat patients even for non-COVID reasons like a car accident, stroke or heart attack, he said.

“We run out of ICU beds on a daily basis,” Ivonne Der Torosian of St. Agnes Medical Center said at a recent briefing, forcing the hospital to convert other areas into spaces that can treat critically ill people.

At the end of August, Dr. Kenny Banh said at a media briefing that he was seeing at UCSF Fresno’s COVID-19 Equity Project about 150 vaccinations a day on average but around 500 coronavirus tests a day — 10 times more than two months earlier. “I wish the lines were flipped,” Banh said, wishing hundreds more people were getting vaccinations.

Health advocates are making efforts to reach out to promote vaccinations, but experts have been disheartened by a lack of interest. At Clinica Sierra Vista, thousands of calls by staffers can result in perhaps 100 vaccinations, Stacy Ferreira, the clinic’s chief executive, said at a media briefing.

In Fresno County, 63% of residents ages 12 and older have been vaccinated with at least one dose. By contrast, in L.A. County, 75% of residents in the same age group have received at least one dose, as have more than 87% of vaccine-eligible residents in San Francisco and Santa Clara counties in the Bay Area.

For pandemic planning purposes, the state defines the San Joaquin Valley as comprising Calaveras, Fresno, Kern, Kings, Madera, Mariposa, Merced, San Benito, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, Tulare and Tuolumne counties.

The region with the second-lowest percentage of available ICU beds is Greater Sacramento, where 14.8% of staffed adult ICU beds were open as of Monday. The comparable figures are 19.7% in rural Northern California, 21.8% in Southern California and 24.6% in the Bay Area.

Statewide, 2,016 coronavirus-positive patients were receiving intensive care as of Monday — down 5% from a week earlier. And across California, 1,428 total adult ICU beds were available.

However, those beds — as well as the specialized equipment and staff needed to operate them — are not spread evenly throughout the state, leaving more rural areas particularly exposed to capacity constraints.

Amid the ongoing surge, which is fueled by the highly transmissible Delta variant of the coronavirus, many California counties are now recommending or requiring that residents wear face coverings in indoor public places as an additional layer of protection.

“The continued increase in hospitalizations is concerning, especially when you look at the non-COVID-19 demands on our hospitals. We need to do something to protect our local hospitals so that we have capacity to take care of everyday medical needs,” Vito Chiesa, chairman of the Stanislaus County Board of Supervisors, said in a recent statement.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.