UC violates civil rights of disadvantaged students by requiring SAT for admission, lawsuits say

The University of California is violating state civil rights laws by requiring applicants to take the SAT or ACT, standardized tests that unlawfully discriminate against disabled, low-income, multilingual and underrepresented minority students, two lawsuits filed Tuesday allege.

The lawsuits, filed on behalf of the Compton Unified School District, four students and six community organizations, demand that the 10-campus UC system eliminate the testing requirement. Any decision by UC to drop the tests — as some prominent UC officials themselves have urged — would play an outsized role in the future of standardized testing in the nation because of the size and status of the premier public research university system.

“Rather than fulfilling its vision as an ‘engine of opportunity for all Californians’ and creating a level playing field in which all students are evaluated based on individual merit, the UC requires all applicants to subject themselves to SAT and ACT tests that are demonstrably discriminatory against the State’s least privileged students, the very students who would most benefit from higher education,” one of the lawsuits states.

The lawsuits allege that UC’s testing requirement violates the California Constitution’s equal protection guarantees and bans on discrimination by state educational and civil rights laws.

UC spokeswoman Claire Doan said the university was “disappointed” by the lawsuits. She noted that UC President Janet Napolitano last year asked the Academic Senate, which sets admissions standards, to review the use of standardized testing and the university has “already devoted substantial resources to studying this complex issue.” The Academic Senate is expected to issue recommendations early next year.

In a letter to UC officials in October, lawyers for Compton Unified and others threatened litigation if UC did not immediately end the testing requirement. The suits were filed Tuesday in Alameda County Superior Court after the groups failed to reach a resolution.

Officials with ACT and the College Board, which owns the SAT, sharply disputed allegations Tuesday that their tests are discriminatory. They said that differences in test scores reflected social inequities in access to quality education, not their exams. They argue that their tests are predictive of college performance and offer a uniform yardstick that allows colleges to compare students across a range of states and high schools.

“The notion that the SAT is discriminatory is false,” College Board spokesman Zachary Goldberg said in statement. “Regrettably, the letter and the lawsuit contain a number of false assertions and is counterproductive to the fact-based, data-driven discussion that students, parents and educators deserve.”

He added that the College Board is working to combat inequalities in the education system by offering free test practice tools and unlimited college application fee waivers. The testing organization also has developed a tool to help colleges understand the socioeconomic characteristics of applicants’ high schools and neighborhoods to put the scores in context.

Marten Roorda, ACT chief executive officer, defended standardized tests as the “only college readiness indicator to make achievement and merit comparable across schools, districts and states” and said the organization was expanding free educational tools.

“It is inappropriate to blame admissions testing for inequities in society,” Roorda said in a statement. “We don’t fire the doctor or throw away the thermometer when an illness has been diagnosed. Differences in test scores expose issues that need to be fixed in our educational system.”

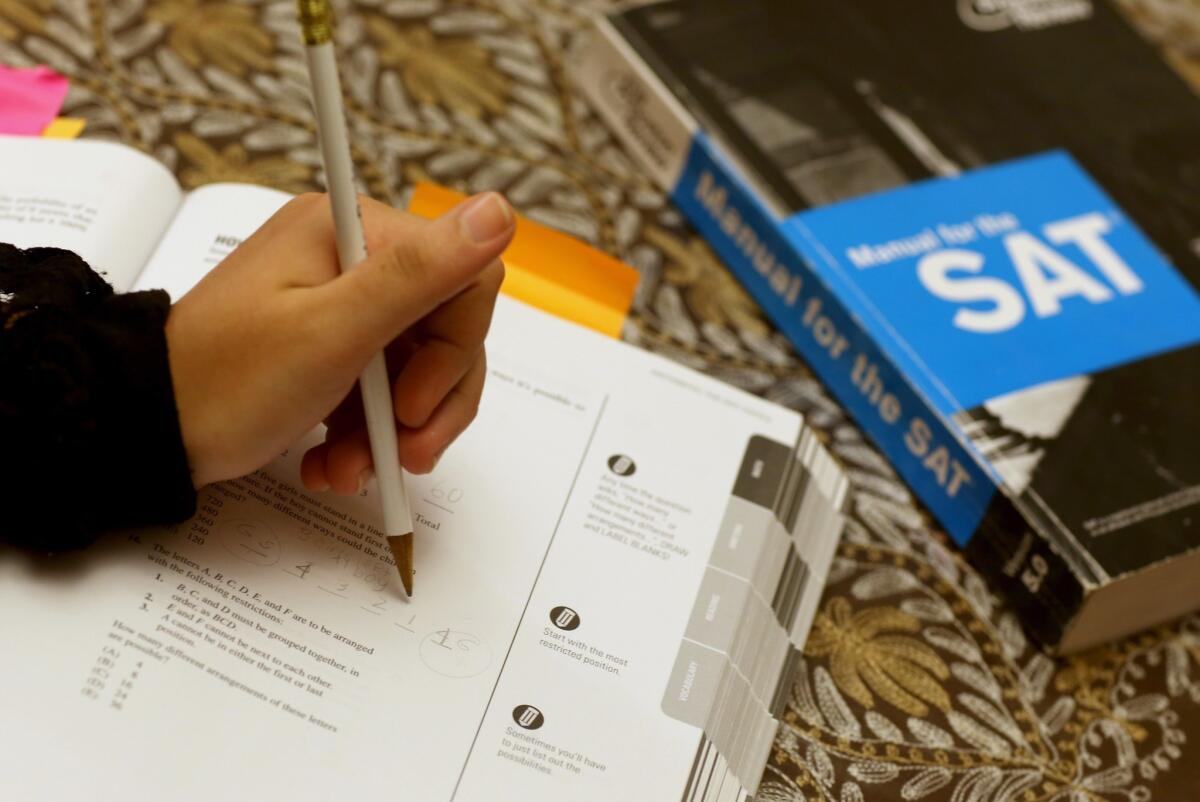

Critics, however, say the exams are an unfair admission barrier to students who don’t test well or can’t afford to pay for pricey test preparation.

The voluminous lawsuits detail the findings of numerous studies that show scores are strongly influenced by family income, parents’ education, and race and that high school grades are the strongest single predictor of college performance.

The suits also detail the history of UC and the SAT, citing documents in which university officials have questioned the use and fairness of the tests for decades but have chosen to use them anyway.

The lawsuits were filed by Public Counsel, a Los Angeles pro bono law firm, and other attorneys on behalf of Compton Unified, Community Coalition, Dolores Huerta Foundation, Little Manila Rising, College Seekers, College Access Plan and Chinese for Affirmative Action.

The other plaintiffs are four students who have high GPAs and resumes reflecting accomplishments but who could not afford quality test prep and failed to secure high scores on the SAT. The students have a history of disabilities, are not native English speakers or are underrepresented minorities.

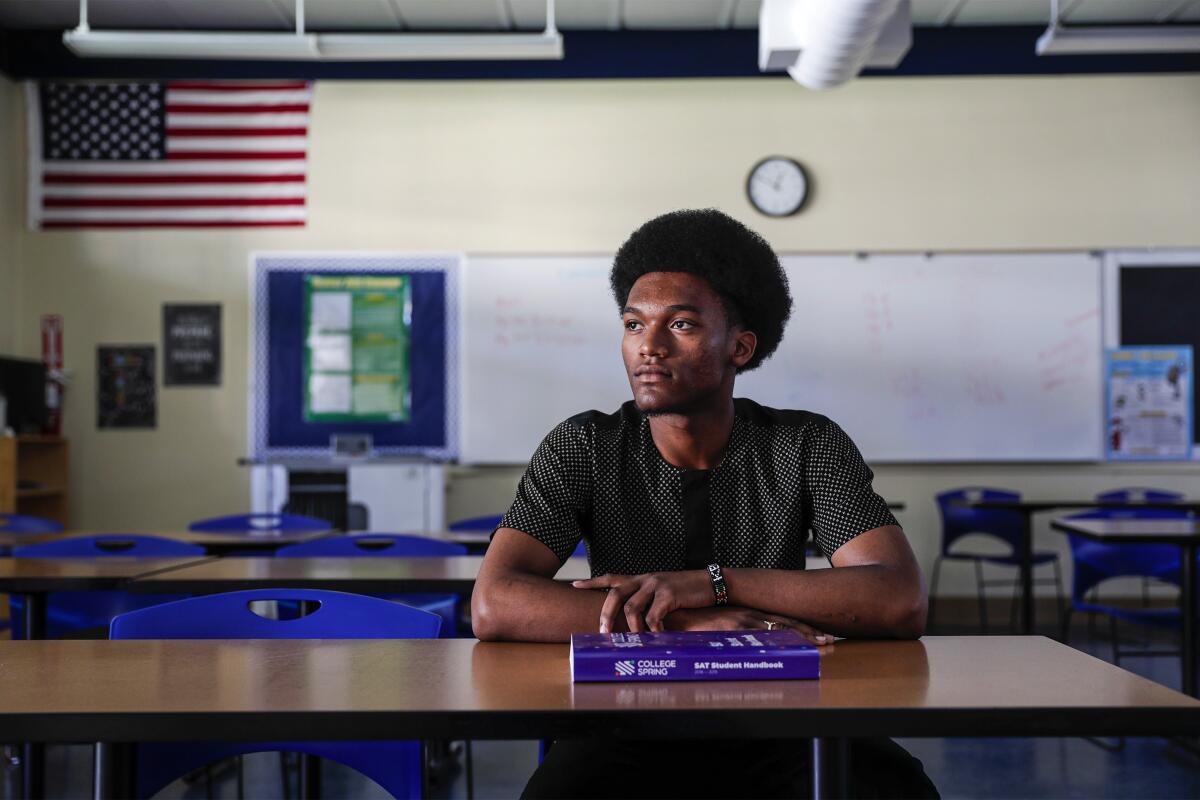

Kawika Smith, a student plaintiff and senior at Verbum Dei High School in Watts, said he was not able to test well because he lacked money for effective preparation, was often hungry and struggled with the trauma of homelessness and a previous sexual assault. He still managed to achieve a 3.56 weighted GPA and dreams of a UC education.

“I was a child with a dysfunctional lifestyle in survival mode and was expected to show up fully present in class,” he said.

The lawsuits note that such disadvantages are also evident among some Asian Americans, who overall score higher on the standardized tests than African Africans, Latinos and whites. One study found that SAT test scores were lower in high schools with high percentages of students of Hmong and Filipino backgrounds compared to those with Chinese Americans.

“These tests are a barrier to education for many Asian Americans groups that have come to the U.S. as refugees or who struggle with poverty like Lao, Hmong and others,” said Janelle Wong, an Asian American studies professor at the University of Maryland, College Park.

Two better alternatives to the SAT, the lawsuits assert, are Smarter Balanced, a standardized test given to all California 11th graders that tests mastery of the state’s Common Core high school curriculum; and the University of Texas policy, which guarantees admission to campuses based solely on high school grades.

Research has shown that Smarter Balanced predicts college performance as well as the SAT and ACT but with far less discriminatory effects on disadvantaged students.

Eddie Comeaux, a UC Riverside professor and co-chair of the Academic Senate task force on standardized testing, said the upcoming faculty recommendations would be guided by fairness, equity and solid research.

The issue is complex, he said, because replacing standardized tests with other metrics won’t eliminate the influence of wealth and privilege in the system. Wealthier students have greater access to writing coaches for required application essays and splashy extracurricular activities, he said, while research has shown that grade inflation is more prevalent at affluent schools.

“We understand that no matter what policy or recommendation we put forth, it’s not going to address all of the privilege that does exist in the system,” Comeaux said. “We just want to make sure we get it right.”

Mark Rosenbaum, a Public Counsel attorney, said students cannot wait.

“The SAT and ACT is hurting young people throughout California, students with stellar records in school,” he said.

Bob Schaeffer, public education director for FairTest, the National Center for Fair and Open Testing, said national momentum was growing to drop testing requirements, with more than 1,000 universities across the nation making them optional — including the University of Chicago, George Washington University and the University of San Francisco.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.