Canada’s Secret to Escaping the ‘Liberal Doom Loop’

How a country can welcome immigrants without triggering a massive populist backlash

The world is burning with the fires of illiberal populism. The flames take on different shapes in different nations. There is Trump’s lurid xenophobia in America, Brexit in Britain, a right-wing government in Poland, a “People's Party” smoldering in both Denmark and Austria, Marine le Pen’s Front National in France, Geert Wilders’s “blond beastliness” in the Netherlands, and the Kultur-warriors of Germany’s “Alternative für Deutschland.”

But in the Canadian wilderness, the fire isn’t catching yet.

For decades, Canada has sustained exceptionally high levels of immigration without facing an illiberal populist groundswell. It is the most inclusive country in the world in its attitudes toward immigrants, religion, and sexuality, according to a 2018 survey by the polling company Ipsos. In a ranking of the most important Canadian symbols and values, its citizens put “multiculturalism” right next to the national anthem—and just behind their flag. In the U.S., those supportive of multiculturalism say they’re the least patriotic; in Canada, patriotism and multiculturalism go together like fries and cheese curds.

To be clear, Canada has not discovered some magical elixir to eradicate intolerance, racism, or inequality, all of which are present in the nation of 36 million. Its indigenous communities, which have endured centuries of brutalization and discrimination, often live under conditions that are still described as “third world.” And the country is not equally welcoming to all newcomers. But at a time when anti-immigrant sentiment and populist politics are sweeping across Europe and America, Canada stands apart.

What’s Canada’s secret? A blend of imperial history, bizarre and desolate geography, and provincial politics have forged something unique in the Great White North. Countries now buckling under the strain of xenophobic populism should take note.

The Dawn of a Multinational Nation

The first seeds of Canadian multiculturalism were planted before the United States technically existed. In the 1760s, the British gained control of French Canada, an area that corresponds roughly to modern Quebec. But back at London headquarters, it wasn’t evident that this frigid plot of land was good for much more than beaver pelts. (Even Voltaire dismissed his country’s outpost as “a few acres of snow.”) So, Britain passed the Quebec Act in 1774, which allowed French Catholics to live their private lives as they saw fit, so long as the law remained in the hands of the British Protestants.

“This was a bold accommodation,” said Peter Russell, a professor emeritus of political science at the University of Toronto, and the author of Canada’s Odyssey. “It was bold for a Protestant regime [the British Empire] to permit a French Catholic population [the French Canadians] to exist and maintain their own culture.”

The Quebec Act provided an accidental blueprint for the Canadian experiment, Russell said. If the United States was a nation conceived in a life-or-death war for liberty, French Canada was a hyphenation hammered out in messy compromise between the public and private realms: English common law in the streets, French Catholicism in the sheets. From the start, Canada was a curious bargain—a multinational nation.

Canada is a “country based on incomplete conquests,” Russell writes. First, the British incompletely conquered the French Canadians in the 18th century. Second, Canada’s indigenous people have won legal victories allowing them to retain large swaths of land. The 2016 Canadian census found that 5 percent of the country’s population is indigenous, including almost one-fifth of Manitoba and half of the Northwest Territories.

“As indigenous people in Canada survived and strengthened their sense of national identity, Canadians have accepted French and indigenous cultures as nations within a nation,” Russell said.

Open Space, Open Arms

To state the obvious, Canada is big and cold and, unless one is trying to circumnavigate the polar ice caps, pretty much out of the way of everything.

These things have their advantages. In Europe, national borders are a political jigsaw puzzle, where straight and jagged lines are carved by centuries of war and death. Canada’s national borders are mostly drawn by geology. The country is bounded by three oceans and the United States. It’s easier to cultivate a history of openness to strangers when outsiders haven’t spent several centuries trying to kill or conquer you. Plus, it’s harder to illegally immigrate to a country surrounded by cold, vast oceans; so, Canada has been spared from sudden, shocking influxes of undocumented foreigners.

But there is a subtler benefit of Canada’s immensity. The country has a lot of space to fill, and it’s always needed outsiders to fill it.

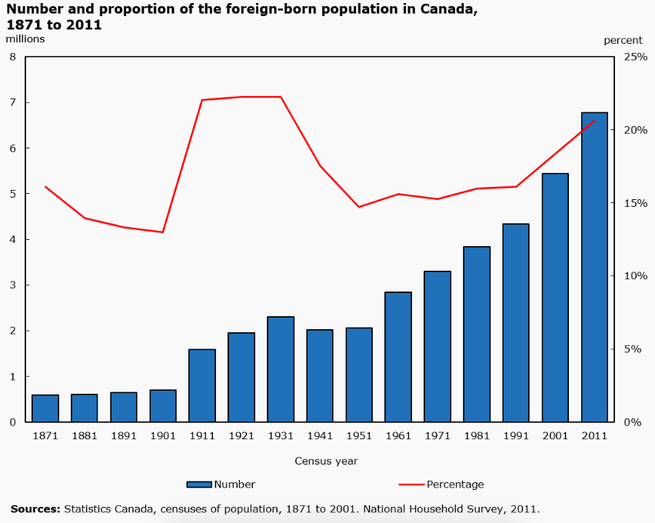

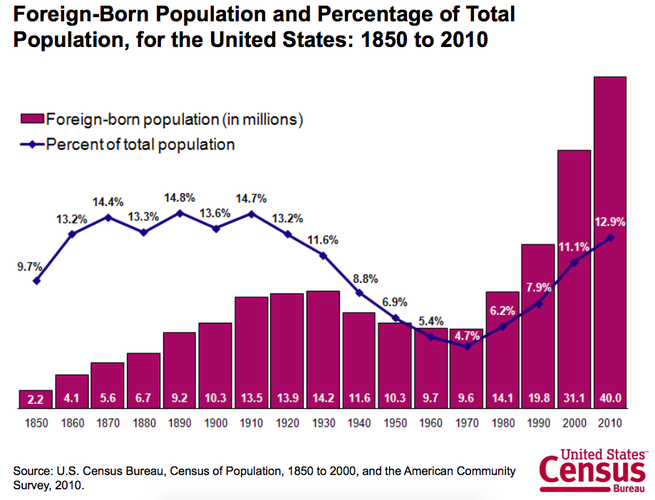

The United States considers itself a nation of immigrants. But, proportionally speaking, it’s got nothing on Canada. Foreign-born Canadians have always accounted for between 15 and 20 percent of the country’s total population since the country’s founding. In the U.S., immigrants have never exceeded 15 percent of the total population since the 1850s. So, with immigrant share—as with national borders—America’s ceiling is Canada’s floor.

With this necessity for foreign workers, Canada has developed a “points-based” system of immigration that carefully selects for skill. Applicants receive points for things like their fluency in English and French, their education level, and the number of years they have worked. Those who exceed the points threshold can be selected as permanent residents. Even conservative Canadians see incoming workers as an economic benefit, avoiding the common (if wrong) U.S. conservative argument that immigrants are a leech on the country’s social services.

Canada has its share of far-right groups, like La Meute and Storm Alliance. But its most successful populist movements to date have been pro-immigrant. For example, the living Canadian politician most commonly compared to Donald Trump is Doug Ford (the brother of the late former mayor of Toronto, Rob Ford). But while the Fords’ brand of populism is alarming in many ways, some aspects of it would be unrecognizable in the United States. For example, they are not free-trade-warring cyclones of white xenophobia. Rob Ford’s approval rating was twice as high among minorities when he was mayor of Toronto, and Doug Ford draws more support from people identifying as Asian-Canadian than native-born Canadian. The living Ford has said he’s “working closely” with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on extending NAFTA to protect free trade.

If you’re an American reading along, the idea of a populist on the American continent hailing globalization and drawing disproportionate support from minorities might cause an acute case of vertigo. And, to be clear, one cannot rule out the possibility that Doug Ford’s bigotry will soon turn hard against minorities. But so far, Canada has mostly avoided that particular brand of conservative populism.

Owning the Libs With … Pro-Immigrant Politics

The final clue to understanding made-in-Canada populism requires a brief tour of the country’s political geography.

For most of Canada’s history, the four western provinces—British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba—have been resource-rich; meanwhile, the eastern metros—including Canada’s political capital Ottawa, its economic hub Toronto, and its cultural jewel, Montreal—have been status-rich. For decades, the province of Ontario set the terms of Canadian economic policy. For example, the Ottawa government slapped tariffs on imports to protect eastern factories. These taxes had the effect of raising prices on imports for westerners. So, the western provinces welcomed free-trade agreements like NAFTA, since these deals cut prices and pushed back against Ontario-first economics.

If globalization was a useful weapon to fight back against Ontario, immigration was a cudgel to take on Quebec. In the middle of the 20th century, the French-Canadian province agitated loudly for independence. To placate Quebec, the Canadian government in 1969 declared French a second official language of Canada. But the country’s conservative parties bristled at the cost of enforced bilingualism. Once again, the east was imposing its cultural and economic will. But this time, conservatives found a surprising ally against biculturalism: Canada’s new immigrants.

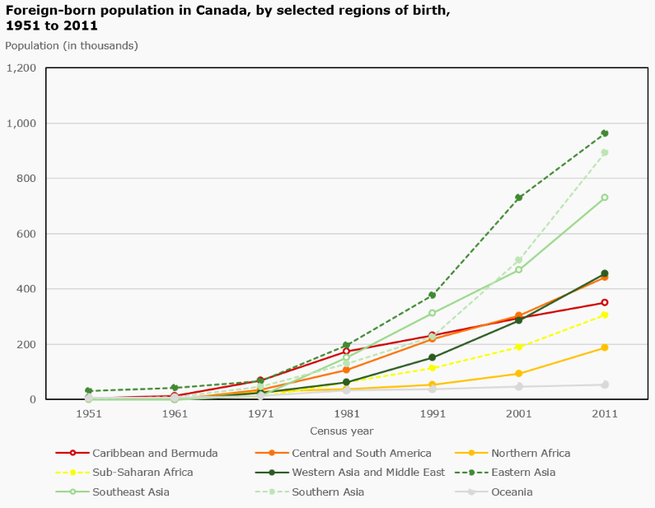

Before the 1950s, Canada’s foreign-born workforce was almost entirely European. But in the 1960s and 1970s, non-Europeans became the fastest growing group of immigrants. “They were from Asia, and Africa, and Latin America, and they questioned this bilingualism,” Peter Russell said. “They said, why just French and English culture? What about us? Where do we fit in?” Conservatives and immigrants alike meant to drown out Quebecois exceptionalism with something like the sentiment: “All Cultures Matter.”

In 1971, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, the father of the current PM Justin Trudeau, offered an ingenious compromise to assuage all parties. Rather than say that Canada was unicultural or bicultural, he created a policy of multiculturalism. He announced that no one group defined Canada and that the government accepted “the contention of other cultural communities that they, too, are essential elements in Canada.” This had a three-part effect, according to Andrew Stark, a political science professor at the University of Toronto. It appealed to new immigrants by honoring their heritage; it accommodated Quebec by retaining French as an official language; and it placated the west by diluting French-Canadian influence.

One might have expected Canada’s equivalent of the Tea Party to have brewed in its western provinces. But the most successful Canadian populists today aren’t really anti-migrant or anti-globalism. Quite the opposite, Canadian conservatives have historically seen free trade and multiculturalism as a weapons to take on the political dominion and cultural elitism of the eastern provinces.

“When the right is leading the cause for immigration and saying to the left, you’re not doing enough to welcome immigrants into the country, it creates a competition to see who can do more,” Russell said. “This, of course, increases the size of the immigrant community and the immigrant vote, which becomes an unignorable political force.” In Canada, multiculturalism isn’t a kumbaya song. It’s hard-nosed politics.

Breaking the Doom Loop

Last year, as I saw right-wing populism sweeping the developing world, I offered a “liberal doom loop” theory to unite several trends in fertility, immigration, racism, and liberalism. In this theory, low fertility and the threat of stagnating populations would encourage some governments to accept more immigrants; this diverse influx of people would make certain groups (particularly white, older, and less educated) afraid of economic and cultural threats posed by other ethnicities; the anxious electorate would back illiberal populist movements to preserve whites’ economic and cultural authority; and these votes would ultimately threaten the liberal welfare state.

But Canada offers a fascinating exception. Like any country, it has its nativist media figures, anti-immigrant gangs, and terrorist attacks meant to shock the country back into a monocultural identity. But with each passing generation, Canadians have become more likely to embrace immigration. Canadians today are more tolerant, not only than their southernly neighbor, but also than previous generations of Canadians. For now, Canada seems to have achieved escape velocity from the liberal doom loop.

What lessons can the Canada example offer other countries? Some of its features defy imitation, particularly its geographical isolation and its distance from the world’s biggest migratory movements. The U.S., for example, cannot instantly recreate 200 years of inter-state relations; its legacy of slavery permanently poisons its relationship with race. White Americans still hold fast to old-fashioned, Westphalian notions that a nation-state ought to signify a sovereign monocultural identity—an idea Canada’s government rejected more than 40 years ago.

But there is a clear lesson worth importing from Canada: When a city or province passes a certain threshold of diversity, pro-immigration politics can become a self-sustaining virtuous cycle. International research on xenophobia has found that whites who don’t know many foreign-born people are more likely to fear their presence, while those who actually know immigrants are much more likely to have positive attitudes toward them. This is true even in the U.S., where, despite Trump’s election, immigration is more popular than any period in the last 30 years. A majority of babies born in the U.S. for the last four years have been non-white. Historic ethnic diversity is not a future the U.S. can choose to accept or reject; it’s the only future on its way. And it's a world where Republicans might finally choose to imitate Canadian conservatives by looking to steal immigrants’ votes, rather than their children.

The physicist Max Planck once said that a new scientific truth doesn’t triumph through persuasion, but rather through attrition, as “its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.” This generation of Canadians has grown up familiar with the idea that immigrants can be liberal or conservative, and now both liberals and conservatives are fighting for immigrants. If American conservatives recognize the political potential of appealing to the foreign-born, the United States will join Canada in the future that may be spreading, albeit fitfully, around the world. “Multinational, multicultural Canada might offer more useful guidance for what lies ahead for the peoples of this planet than the tidy model of the single-nation sovereign state,” Peter Russell writes. “Canada could replace empire and nation-state as the most attractive model in the 21st century.”