Paris Green: The Trendy Color That Killed Many in Victorian Society

It was said that at the Paris Opera one evening in 1864, Empress Eugenie wore a gown so breathtaking it made newspaper headlines the very next morning. The dress was a spectacular deep-set green, its colors vivid enough to remain unchanged by gaslight.

Soon after, “Paris green” became the color of the social elite, not only on their garments but adorning their walls as well. The trend would eventually reach Victorian England, and people would die as a result.

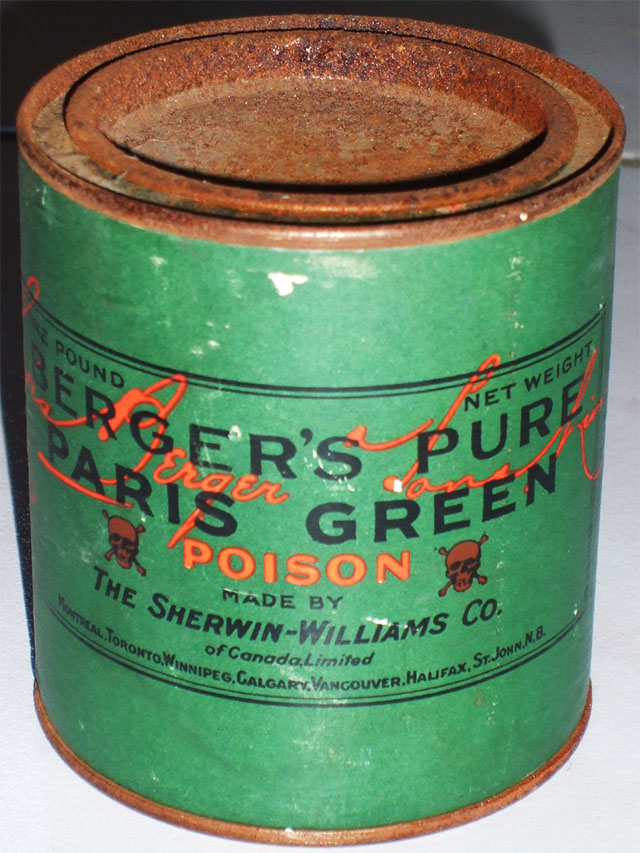

Paris green, also known as emerald green, was one of many hues—including Scheele’s green, the first of its kind—that would end the lives of people in the Victorian Era. The resplendent pigment was the creation of chemists who found that mixing copper with arsenic resulted in a dye that was brighter and longer-lasting than other greens in the market.

As we now know, arsenic is a highly toxic substance that causes skin lesions, vomiting, diarrhea, and in some cases, cancer. In the 19th century, however, it was as ubiquitous as plastic, finding its way into candy, paper, toys, and medicine; for it to be used as a dye for clothing and accessories was all too normal.

There were warning signs, of course. In her book, Fashion Victims: The Dangers of Dress Past and Present, author Alison Matthews David recounts an 1859 investigation into the health of artificial flower makers by Dr. Ange-Gabriel-Maxime Vernois, a physician whom Napoleon himself would consult. The workshop Vernois had visited was suffering from a fatally ill staff. He noted that many of the male workers had ulcerations on their green hands, yellow nails, and crater-like scars on their legs. Their genitals had painful lesions on them, sometimes stretching out to their inner thighs. The female workers, on the other hand, had poor appetites, constant headaches, and an anemic pallor to their skin.

It was upon watching them work that Vernois made the connection between their ailments and the green dye. He observed that the

After Vernois reported his findings, the French and German governments passed laws that restricted the production of arsenic-based pigments, but they were largely ignored by the British Government. Even the death of Matilda Scheurer, an artificial flower maker in London, was ruled as an “accidental poisoning”, despite the fact that the now-green whites of her eyes indicated that prolonged exposure to arsenic was the most likely cause.

And so Paris green, the pigment adored by the French Empress and used in the works of artists such as Cézanne, Seurat, Manet, and Van Gogh, remained in vogue in the Queen’s country.

According to Lucinda Hawksley, author of Bitten by the Witch Fever: Wallpaper and Arsenic in the Victorian Home, the use of arsenic green in wallpaper was already fashionable, even before Empress Eugenie’s appearance at the Opera.

In 1862, physician Thomas Orton was called in by a couple by the name of Turner to investigate the mysterious illness that had killed three of their children, and threatened the life of their remaining daughter.

Earlier doctors concluded that the children had suffered from diphtheria, and their symptoms were consistent with those of the condition. However, Orton noted that none of the family’s neighbors had caught the disease, leading him to suspect another cause: the green wallpaper that covered the walls of their home. It had long been a rumor in the medical community that the arsenic in the paints might be released into the air under certain conditions, creating a poisonous atmosphere in the rooms that used them. Orton believed this to be the case.

Though he was unable to save the Turner child’s life, he immediately asked to conduct an autopsy on her body. A certain “Dr. Letheby” ended up being the one to test samples of her tissue, and he determined that the cause of death was, indeed, arsenic poisoning. At the inquest, however, the presiding judge found his findings “objectionable,” leading the jury to rule the child’s death as a result of natural causes.

In the years that followed, the use of Paris green and other arsenic-based greens reached their peak, although with a rising undercurrent of fear. While the colors remained fashionable, more and more stories of arsenic-related deaths came to light. Even the Queen herself was not immune to the panic.

In 1879, a visiting dignitary was given

Despite all this, there was no legislation written to regulate the production of arsenic-based pigments; the closest thing the British government had done in that regard was to pass a bill controlling the amount of arsenic in food in 1903. It would turn out that the buying public wielded more power over the industry than the law itself; due to a sharp drop in demand for Paris green dresses and wallpapers, production of the pigment had stopped altogether in a number of facilities. Today, arsenic-based greens are a thing of the distant past.

The fear of green still has its vestiges in modern media, however. Green is often seen as a color of malice, often seen on the skin and clothes of movie antagonists. Some theorize that the use of green to denote poison in cartoons and early- to mid-1900s art was directly influenced by the arsenic scare. It was only during in the 1980s and '90s that green started being seen once again as a favorable color, in large part to that era’s environmental movement—ironically, symbolizing life.