This story is part of ELLE's America Redefined series. To read the full series, click here.

I went to Greenville to meet Flora Shorter. I wanted to ask her about the death of her son, Ronnie Lee Shorter, who three years earlier had been shot by local police in front of his home. He was 44.

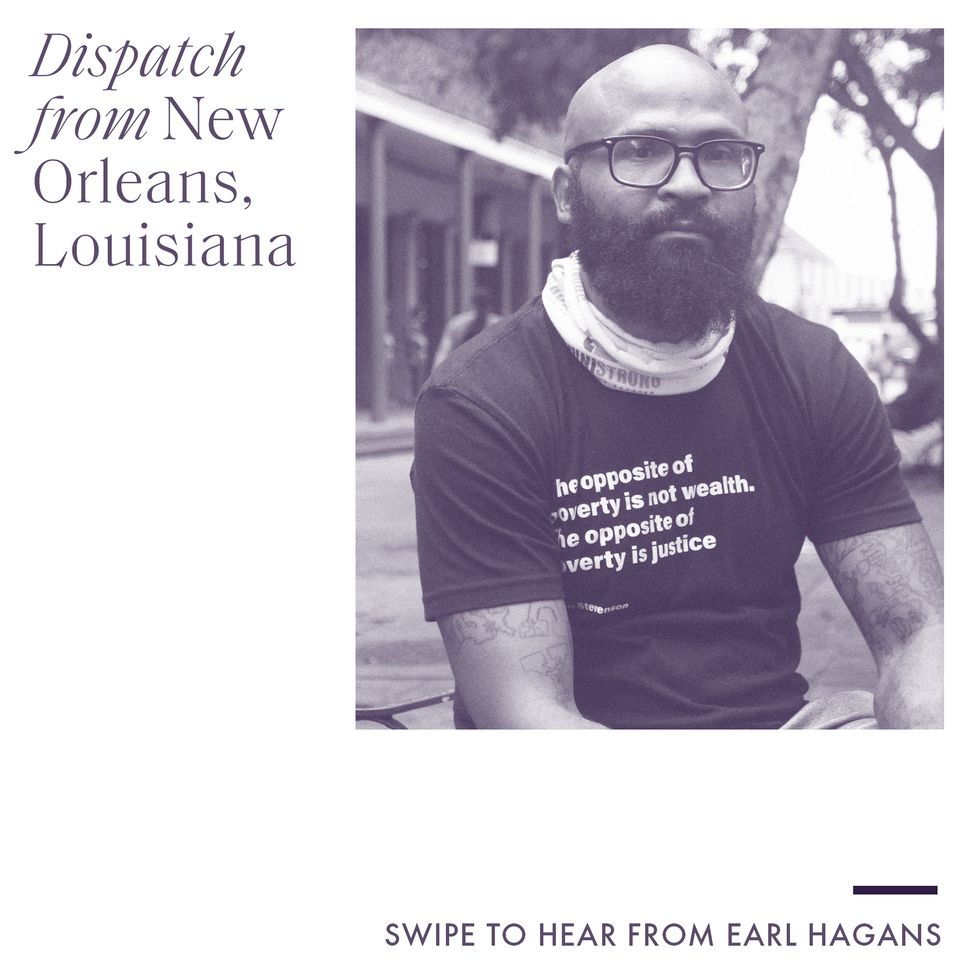

Sometime in June, I had come across Ronnie’s story in an article in The Clarion-Ledger, the local paper in Washington County, Mississippi. He was shot in 2017. Three years later, his family still knew next to nothing about the circumstances surrounding the shooting. I found Ronnie’s cousin, Emanuel Powell, a recent Harvard Law School graduate and now a staff attorney at ArchCity Defenders, a legal advocacy agency assisting underserved citizens in St. Louis, primarily people of color.

He connected me to Flora.

During my stop in Memphis, I scheduled a day trip to Greenville, in the Mississippi Delta, to meet with her. Memphis was gloomy and damp when I got into the rental car for the three-hour drive. Google Maps warned me the route was impacted by Depression Delta. What’s the difference between a depression and a hurricane? I asked Siri.

“Here’s what I found.”

Depression is the first stage of a “tropical weather event” and are like cyclones with lots of strong winds. So just heavy rain with some wind?

I texted Emanuel: “ETA is 130.”

The yard in front of Flora’s peach-painted home is crowded: There’s a round, marble table next to a swan sculpture on a concrete base. A three-tiered water fountain. A garden with yellow and purple flowers. And plants, lots of plants, some in large orange vases. A PRIVATE PROPERTY sign.

Flora reminded me of my mom, down to her reserved gaze to the ground when she searched for the right words. She had on a blue tracksuit with yellow stripes down the sides. Her natural layered pixie cut was fierce: dark brown in the back and blonde in the front. We all wore masks, and hers had a picture of Ronnie on it.

Sitting next to her was Monica Harris, Ronnie’s cousin, who first got the call that night. She wore a black shirt with “Just Do It” in lime ink, and dark purple tights. Her curls were loose and shoulder length. On speakerphone, on the golden center table in front of me, was Emanuel. Flora’s home was cozy and charming. Like, some melting sweet potato casserole with marshmallows and candied yams stay on the ready in the kitchen. Her living room reminded me of my childhood, where mom would hoard everything from when we were weeks old to pieces of decor you have to look at twice. Every corner held something.

Her upholstered sofa set was cream with thick gold trims. Six large throw pillows dressed each one. I plopped down at the edge of one of the sofas.

I got through a couple of sighs. Then we started.

What happened was, Ronnie’s car had a flat tire. It was a Saturday night in January, and he was on his way home from a friend’s funeral. Rather than drive on the flat, he decided to park at Flora’s until morning and his cousin drove him home. When he got there, he called his mom as he was winding down and getting ready to go to bed.

“We always talk on the phone,” Flora said, her soft voice, thick with a drawl, unsteady.

They had made a habit of it over the years of ending the day like that. He was her only son, 44 but still her baby. As they talked that night, Ronnie said he heard something outside his window.

“Ma?” Ronnie said.

“Hmm?”

“Hold on a minute,” he told her, distracted. “Somebody out here in my yard.”

“Don’t go to the door,” she told him. It was almost 10 p.m. “Call the police!”

“Let me call you right back,” Ronnie told his mom.

My eyes were locked on Flora’s. I was taking a long time between breaths.

Five police officers were responding to anonymous 911 calls to Ronnie’s neighborhood. There were reports of shots fired, the police said later. They drove by a few times and didn't see anything. Still, Flora said, the way she had heard it, one person kept calling. The anonymous caller directed them to Ronnie’s house.

As far as the family knows, based on the few records they were able to get a hold of so far, the officers showed up without their lights on and parked their cars away from Ronnie’s house. Two officers stood behind two big trees in the front yard. One headed to the back of the house, and the other two remained across the street, out of sight.

When Ronnie got out and made his way down his yard, one of the officers shined a light at his face. The officers later said Ronnie had come out firing a gun, and that they returned fire. Of the eleven shots, the fatal shot was the one to the back of his head.

He died on the street. The coroner’s report lists a “view of body” time of 9:53 p.m. But when the cops had called for paramedics at 9:09, they had already noted that he was dead on the scene.

I swallowed hard. It was quiet for a long minute.

Monica was at her house with her brother, Boo—another of Ronnie’s cousins, Lawson Shorter—just two doors down from Flora, when she heard her brother scream in the living room.

“What’s wrong?”

Her brother said, “My homegirl just called me and told me that the police at Pie house and they just shot him,” he told her. “C’mon!” Pie was what the family called Ronnie.

Monica called Flora as they ran out to the car. “Somebody just called Boo and told him Pie just got shot,” Monica said into her phone when Flora answered.

“Nah, that can’t be true,” Flora told her. “I just got off the phone with him.” Maybe it was the other Ronnie in town?

“Well come on out, get in the car, we fin’na go.” They all got in the car and head towards Neff. On the way, at the intersection of Highway 82 and Broadway, they see about 25 cop cars leaving that area, heading towards the police department. When they arrive, they see cop cars on Ronnie’s block. Lights going.

They stretch their necks to see towards Ronnie’s home, and that’s when they see his body. Laid out on the ground. Face down, blood leaking. His hands cuffed behind him. They all try to push through to get closer, but police officers had blocked off the scene.

“This is his mom! This is his mom!” Monica and Boo barked at them. Confused. Wanting answers.

“You can’t go up there,” one of the officers told them, according to Monica.

“Well, what happened? What happened? What’s going on?” The family members spoke at once and asked the same questions repeatedly, and sometimes over each other, in the commotion.

None of the officers spoke to them, they told me.

Around midnight, when Ronnie’s body had been removed, Flora, Monica, and the rest of the family were finally able to get close to the house.

There were still a lot of police around. The family members tried to get more information from the police, but got none. They couldn’t go into his house—the police told them that another group of officers needed to look at the crime scene undisturbed, but they promised they wouldn’t search Ronnie’s home.

The next morning, when the family were finally able to get into his house, they told me the place looked to be ransacked. They saw bullet holes in the walls.

That Sunday morning, the chief of police and two investigators came to Flora’s house. “Sorry for your loss,” the chief told her. She asked so many questions:

What exactly happened?

How did Ronnie go from catching up with his mom on the phone to being shot down steps outside his home?

“Everything is still under investigation,” the chief told her. When the grand jury met weeks later, the family wasn’t even informed—Monica learned about it in the local paper. What upset her the most in the days and weeks following Ronnie’s death was how he was described. She felt local news outlets simply repeated the same thing the officers had reported, never once speaking to the family. Portraying Ronnie as a threat, mentioning the gun in his hand. To this day, the family says they are still asking the police department to see the weapon they claim Ronnie fired at them. Fingerprints. Spend rounds. Anything that would corroborate their story that Ronnie came out shooting.

They are still waiting on answers to how and why the officers were there in the first place, and question the protocol they followed that night. Why didn’t they just knock? Or turn on their car lights?

And where are the 911 tapes? Was there really an anonymous caller who kept calling? Even the Washington County coroner, who determined Ronnie’s death to be a homicide, has joined with his family in asking for more information from the police.

“We've been fighting effectively for years to just get as much information as we can about what happened that night,” Emanuel said. The family filed a case against the city in January by themselves (“pro se”) and are waiting for the court to appoint an attorney. They are still in the discovery stage, looking for more information on what happened. They are also hoping to get Ronnie’s Law passed, which they hope would improve transparency in the Mississippi police department.

“These types of killings have been the norm for Black people in the Mississippi Delta,” Emmanuel continued, over the speakerphone. “And it feels, unfortunately, how it has always felt, like: To use the imagery of George Floyd, there has been a knee on our necks for so long. And even though there's so much conversation happening around the country, it still hasn't trickled down to the Delta—trickled down to Mississippi—that we should also be getting some of this social change that’s supposed to be happening.”

Right now, Flora said, it feels like “we still have no freedom in this country.”

The room fell quiet again.

They told me more about Ronnie, the person. He went to Coahoma Community College. He was all about his family. Played quarterback in high school, ran track.

“Everybody loved Pie,” his mom said. “Everyone got along with Pie.”

I couldn’t hold it in any longer: “Why do you call him Pie?”

They laughed. Growing up, they told me, Ronnie had chubby cheeks. Like, really chubby. Like ate-a-whole-lot-of-pie cheeks. We laughed, and it was good to laugh, like coming out of a pitch-dark room.

As we say our umpteenth goodbye and do a dance by the front door, I tell Monica I’m starving and in need of caffeine—I hadn’t had my black goodness all day. Nearest coffee shop?

She tells me to follow her to the McDonald’s on Highway 82 off South 9th Street. On the way, she said, she would show me Ronnie’s old house on Neff Street.

Monica stood on the corner of Neff and Highland, across from her cousin’s old home. Where she and her Aunt Flora stood that night, clutching each other, watching the chaos of flashing lights and neighbors peering out windows and Ronnie lying face down.

“Right there,” she said, pointing to the ground.

His body.

This day, puddles from Depression Delta filled the gaps in the cracked pavement. His was the second house once we turned left onto the street. Out front: a bright yellow sign with a missing O and Y: SL-W CHILDREN PLA-ING. The yard was barren, with patches of abandoned grass and brown dirt. A green truck was tucked under the carport to the side.

She retold how they couldn’t go to him from “right here where we had parked.” And how from this or that angle all they could do was just stand there, watching as the red and blue lights blinded them with the arrival of more cop cars.

As we stood there, replaying that night for the second time, the current owner, an older woman with a pale nightdress on, came out to see what we were doing. Monica waved at her and said she had just called to tell them that we’d be stopping by. She walked back inside.

She continued: “There was a cop there, there, and one behind the house, over there.” She pointed to every corner the officers hid that night as they waited for Ronnie to come out.

I could barely form sentences when I arrived and began to order at McDonald’s. “So that’s, a Happy Meal with the four-piece chicken nuggets, small fries. And another order of large fries? With a large coffee?” The cashier judged me. Hard.

Yes, lady, I am indeed eating my feelings.

“What toy?”

“What what?”

“For the Happy Meal.”

“Oh. Whatever. None. Whichever is fastest.”

Dead stare. She listed the options.

“The gender-neutral one is fine,” I said. I just wanted my coffee.

I sat in the Hyundai and studied Google Maps. Two hours and fifty-three minutes back to Memphis. Tomorrow’s attempts are Charlotte and Pittsburgh via two American flights. At least I’ll get a break from driving, I thought.

After talking with Flora, Monica and Emmanuel, my soul just felt…gone. Their story was shocking and not shocking at the same time, and that’s one of the core problems Black people face: The unimaginable doesn’t exist, because you don’t even have to imagine it. It happens with regularity. And when the shocking ceases to be shocking, can we count on anyone to act?

I needed to fill the void with comfort, with food, with anything. The rain had stopped. There were huge puddles everywhere. On the Mississippi landscape, pockets of dark gloom lurked under blinding white patches of sun off in the distance.

I looked inside my Happy Meal and inhaled the nuggets.