As she sat before the man, her legs dangling below the armchair – not yet long enough to reach the floor – Grace’s* heart began to pound. The lamp above her felt like a spotlight. The Bishop, a man in his mid-forties in a dark suit, gazed across the table between them and into what felt like her soul. But she wasn’t going to let that deter her.

The Bishop smiled, deep-set creases eroding the plains of his face. She hadn’t noticed those before. And then he spoke.

“Do you have faith in and a testimony of God the Eternal Father, His Son Jesus Christ and the Holy Ghost?” he began.

“Yes,” replied Grace, quickly.

“Have you ever had impure thoughts?”

“No.” She chewed her lip a little.

“Do you smoke or drink alcohol, coffee or tea?” probed the Bishop.

“No,” Grace responded. She had established a rhythm now.

“Do you steal?” he quizzed.

“No,” Grace said solemnly.

It was in this “worthiness” interview, a common practice for young people in the Mormon faith, that Grace first learned to lie. And she’s been doing it ever since.

In an age where our lives are viewed through the prism of social media, Love Island is adored by millions and we've survived an actual US President who cried “fake news” at the first sniff of criticism, the lines between fiction and reality are more blurred than ever. At the same time, the Belle Gibsons, Anna Delveys and Tinder Swindler's Simon Leviev of this world continue to go viral; a new scammer seems to hit our feeds every week, each spinning a web of lies more intricate than the last.

These stories of famous tale-tellers may be large-scale, but they’re not unique. Not all deception hits the headlines, and only a fraction of it is ever uncovered. Studies have proved that people are better at lying online than face to face, so with 65 billion WhatsApp messages sent every day, how many lies are being batted back and forth daily? We all lie, but there’s a difference between diplomatically telling a friend her new haircut looks great and fabricating your entire existence.

So, what does make a person lie to the extreme? And with technology to enable it now at our fingertips, is it suddenly becoming easier than ever before?

Using a digital disguise

When Grace opens her laptop, she becomes someone new. She leaves behind her plain, blue bedroom, her friendless existence, and becomes the thing she most desires: popular. At 18, lying as regular part of who she is. "I can craft my persona into anything I want, and that's exciting," she tells me over the phone, six years on from that worthiness interview. It doesn’t go unconsidered that I have no way of confirming whether anything Grace tells me is the truth. But I want to believe her, after finding her online, anxiously seeking advice from strangers about how best to untangle the many lies she’d told.

Grace grew up in a Mormon community in midwest America, a religion in which “you’re either totally good or totally bad”, she tells me. The worthiness interviews are a means of determining this, and in her first ever one she slipped up. She admitted to having stolen sweets and was punished. When the next interview came around, Grace lied. But the idea that she was fundamentally a bad person had already been internalised, and it soon dawned on her that she could harness the art of lying to boost her self-esteem.

A self-described introvert who’s “never been normal”, Grace struggled socially, taking solace in online forums. But it wasn’t enough just to blend into the conversations; Grace wanted attention, and she knew how to get it. “I wrote a blog post detailing how I’d been in a car accident and was paralysed from the waist down,” she confesses. The post served its purpose; she was flooded with messages.“It basically made me really popular,” Grace tells me. “It felt good because I’d never been popular in real life.”

From there, the lies spiralled. Her sister had died of cancer; she came from a family of 10 children; she had an IQ of 140. And hours and hours of research went into ensuring her stories were watertight. All this, interspersed with elements of the truth. “To make it seem authentic,” Grace says.

For years, she didn't feel any remorse. “There was no guilt. I just wanted to chase that feeling.” But she’s become close to two people from her online forum, and they’ve suggested a meet-up. Grace is now in a bind – with no other friends, she desperately wants to go. But she can't. These people believe she’s paralysed from the waist down. She has to constantly swerve conversations about meeting up (a tactic that will only last so long) or face her lies unravelling and risk losing the only friends she’s got. She still hasn’t decided which approach to take.

Fake friends

It might be easy for liars to convince themselves that their deceit doesn’t really harm anyone, but lying is pretty much always far from victimless. For those who fall prey to the charms of a compulsive liar, especially when it involves money, love – or status – the stakes are high. And for one person, the stakes climbed up so terrifyingly high that they became the basis of a smash hit Netflix series.

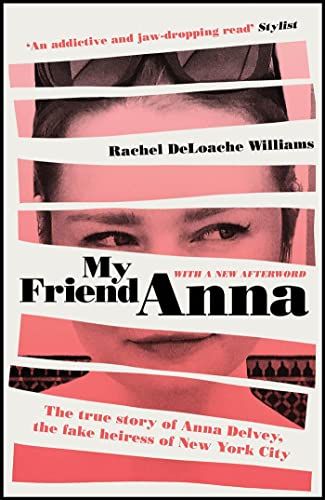

The smirk on Anna Delvey's face during their final showdown is etched in Rachel DeLoache Williams’ mind like a tattoo. “I asked her all of these questions and the way she had an answer for everything... it was just sport for her,” Tennessee-born Rachel tells me when we meet in London. Rachel was drawn to Anna when the supposed heiress made a concerted effort to befriend her in New York in 2015. She became immersed in Anna’s life – and all the private jets, five-star suites and crisp, Provence rosé that came with it.

The problem was, none of it was real – as millions of viewers now also know after watching the show about her scheming, Inventing Anna. Anna Delvey wasn’t the enterprising socialite set to inherit millions that she claimed to be, she was a fraudster (whose real name was Anna Sorokin), busy conning banks, hotels and friends out of hundreds of thousands of dollars. Rachel was one of her casualties.

Anna’s “allure” proved irresistible right up until the end, when the murky truth became inescapable. It was Anna’s “scatty” nature – along with the clear signs of wealth – that meant Rachel stepped in without hesitation to temporarily foot the $62,000 (around £47,000) bill for a luxury Moroccan holiday when Anna had 'problems' with her own cards. But Anna didn’t have the funds to reimburse her – and she never intended to.

Anna was sentenced to 12 years for grand larceny but was released early for good behaviour, however she was quickly placed back behind bars for VISA issues. She’s been punished (to an extent) for the financial aspect of her crimes, but the real wreckage of her lies – the emotional trauma – isn’t something that can be corrected with a stint in jail.

“Before, I would have told you that I was a pretty good judge of character. So the fact that she singled me out, got so close to me and then betrayed me was deeply painful,” Rachel admits. Anna left a trail of anxiety, self-doubt and vulnerability in her wake as she trampled out of Rachel’s life. But where was the punishment for that?

“I don’t expect she’s going to grow from her time in jail, except maybe to acquire some scary skills from some new friends,” Rachel tells me ominously.

"[Lying] is usually to do with what they think is aspirational," psychologist Dr Jane McNeill tells me, which would certainly make sense when it comes to Anna's jet-set lifestyle. An alternative theory, says experimental psychologist Tali Sharot, is that lying is a "slippery slope" where "dishonesty grows and grows".

Her research suggests that the more we lie, the less our brains elicit an emotional response. It would explain why falsehoods often start small, but then snowball into something far more elaborate – and it can hurt just as much, if not more, when there's a romantic element to it all.

Lying for love

When Julia* started talking to Stefan* on Twitter, she was excited. A keen cyclist, she was impressed by his tales of road racing all over the world. After one date, they decisively entered into a long-distance relationship spanning between Stefan’s home in remote Scotland and Julia’s city life in London. Ahead of date number two, Stefan phoned Julia: “Pack your bags. I’m taking you to Paris.” Julia was giddy. It was just the kind of romantic whirlwind she had dreamed of.

When she met Stefan to catch the Eurostar later, however, it became clear the trip was not to be.“I’ve forgotten my passport,” Stefan cursed. “I sent it to the Indian Embassy for my cycling trip and they never sent it back.” Julia was confused. “Why would he plan a trip to Paris if he didn’t have his passport?” she thought. But Stefan was already beating himself up about it; there was no use making the situation worse. They took a weekend by the sea instead and all was forgotten.

Six months later, Julia had packed in her life in London, and moved up to Scotland to be with Stefan. They’d grown close quickly, as he opened up about his daughter from a brief relationship that had ended years ago. They bonded over their shared vegetarianism and their love of the outdoors. “I’m a bit impulsive anyway,” Julia tells me when we meet over coffee to go over what happened, almost nine years on. “So nobody felt the need to warn me against it.”

Within weeks of relocating, the real Stefan began to emerge. His bike sat gathering dust in the shed. He spent days watching reruns on the television at home. One morning, she caught him tucking into a bacon sandwich. In fact, little about Stefan was true. The “brief fling” with the mother of his child was actually his ex-wife, only very recently divorced. Oh, and his name wasn’t Stefan.

"His mum pulled me aside and said, 'Why do you keep calling him Stefan? His name is Steven,'" recalls Julia. She was baffled. Why would he lie about such basic things?

Stefan’s deceit continued to grow, yet whenever Julia confronted him, he did what he did best: lied. After two years of manipulation, Julia found the strength to leave. But the emotional damage was done. She struggled to shake the feeling that she was gullible. “I didn’t know what to believe any more,” she admits. When she met someone else four years on, she wrestled at first with believing that he was genuine. “For the first year I was on high alert. I was convinced that he’d reveal himself to be someone different,” she says.

How can someone lie so habitually, so callously and just... not care? It's the first question that springs to mind for anyone blessed with the gift of empathy. What quickly follows is usually an assumption of sociopathy, psychopathy, perhaps instability.

But the truth is, no one really knows. Grace describes her compulsion as an “addiction” that, when satisfied, delivers her “a dopamine hit”. The neuroscientific research to prove this is limited. One study suggested it discovered the first evidence of structural abnormalities in the brains of deceitful individuals, having noticed a pattern of more “prefrontal white matter” in those who lie regularly. But is this something a person is born with (nature)? Or is it a physical change that develops as a result of a traumatic environment (nurture)? It’s almost impossible to say.

“A compulsive liar is not a scientific construct,” psychiatrist Dr Neel Burton tells me. “It’s just a term people use. We don’t have a definition for it.”

Anna Sorokin seemingly didn’t care who she hurt as Anna Delvey, but she knew what she wanted: status. Steven may have morphed himself into Stefan to become a more aspirational version of himself. Grace plainly admits her fictions were driven by the need for attention. Though each scenario is different, one thread binds each liar together: low self-esteem. All paths lead to one place: a desire to be more.

The only medically diagnosable condition there is for compulsive lying is Munchausen syndrome, in which a person “pretends to be ill or deliberately produces symptoms of illness in themselves”. The clinical cause of this? Low self-esteem. “It’s seen as a need to attract attention in someone who lacks it,” explains Dr Burton. “[Usually], when people tell a big lie, it’s not because they want to deceive people or because they’re ‘evil.’ It’s because they’re in desperate need.”

The internet makes it easier to lie. With photo-editing apps, we can manipulate our entire appearance in seconds. Websites like Ashley Madison actively facilitate deceit. A Google search for “fake job reference” brings up more than 55 million results. And to some extent, we all live double, or even triple lives in the way we present ourselves online, at home and at work every day.

This is the world we live in. Real life goes hand-in-hand with a virtual reality – social media – that we know, and accept, damages mental health and self-esteem. It’s a concerning combination; the perfect recipe for a breeding ground of liars to come. And when you think about it, with a permanent shield of pixels between us, how can we be sure we truly know anyone at all?

What happened next:

Grace has now told one friend the truth. They weren’t as angry as she expected, but have asked for evidence next time she tells them something. Knowing someone wants to be her friend for who she really is has given Grace confidence.

*Names have been changed. This article originally appeared in the February 2020 issue of Cosmopolitan UK.

Follow Cat on Twitter

My Friend Anna: The True Story of Anna Delvey, the Fake Heiress of New York City by Rachel DeLoache Williams is out now:

Cat is Cosmopolitan UK's features editor covering women's issues, health and current affairs. news, features and health. The route to her heart is a simple combination of pasta and cheese (somewhat ironic considering the whole health writing thing), and she finds it difficult to commit to TV series so currently has about 14 different ones on the go.