The theory that may explain what was tormenting the afflicted in Salem’s witch trials

Three hundred twenty-five years later, there are still some unresolved questions about the Salem witch trials.

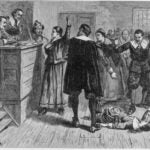

The questions aren’t about whether the people killed in 1692 — 19 executed by hanging and one pressed to death — were actually witches (they weren’t). Rather, what was it that plagued the young girls whose physical “fits” precipitated the first accusations of witchcraft?

The fatal frenzy in 1692 began after the 9-year-old daughter and 11-year-old niece of Salem’s Puritan minister, Samuel Parris, started behaving strangely and erratically. The “fits” soon spread among other young girls in the village. When doctors were unable to provide a medical diagnosis, it was decided that the girls must have been possessed or tormented by witches.

But it remains unclear today: Were those girls genuinely afflicted by something? Or were they faking it?

“That’s one of the big questions of Salem,” said Emerson Baker, a history professor at Salem State University and expert on the witch trials.

Modern theories about what was afflicting the girls have ranged from epilepsy to boredom to ergot poisoning. But most experts agree that these causes alone can’t be attributed to the girls’ anguish.

Baker says it’s possible that a few of the accusers were purposefully faking their symptoms. However, he says that his ultimate conclusion after years of studying the events is that they were actually suffering from psychological ailments.

Foremost among them is something called mass conversion disorder, a psychogenic disorder that — ironically — made a suspected return to the Salem area more than 300 years later.

“People are in such mental anguish, for a variety of reasons, that literally their minds convert their anxieties to physical symptoms,” Baker told Boston.com.

Baker acknowledged that the conversion disorder — a term introduced by Sigmund Freud and otherwise known as mass hysteria — is “still kind of a controversial diagnosis today.”

“It’s hard to make that diagnosis 300 years in the past without the person right in front of you,” he said, adding that it’s possible that a combination of psychological elements played into the girls’ odd behavior.

Dr. Robert Bartholomew, a medical sociologist in New Zealand who has collected more than 3,000 cases on conversion disorder dating back to 1566, says the Salem witch trials were “undoubtedly” a case of the psychogenic condition, in which “psychological conflict and distress are converted into aches and pains that have no physical origin.”

“While the mechanism is poorly understood, there is no question that it happens,” Bartholomew told Boston.com in an email, adding that what happened in Salem was likely an example of “motor-based hysteria,” one of the two main forms of conversion disorder.

“It is very rare in the Western world and arises from long-term stress which results in disruptions to the nerves and neurons that send messages to the muscles and brain,” he said. “Your body goes haywire: twitching, shaking, facial tics, garbled speech, trance states.”

Bartholomew said that outbreaks appear slowly over weeks or months and take as much time to subside — but only “after the stressful agent is no longer believed to be a threat.”

The afflictions in Salem ended in October 1692, around the same time the special court created to try witchcraft cases was dissolved.

According to Baker, examples of what could bring on conversion disorder include a repressive family life or post-traumatic stress disorder. He noted that several of the afflicted girls were refugees who had lost their homes and family members in King William’s War. Of the cases studied by Bartholomew, he said 99 percent involved “a majority of females.”

“The interesting thing about it is today mass conversion tends to be most common in teenagers, and overwhelmingly teenage girls,” Baker said. “And it tends to start out at the top of social order.”

He pointed out that after Parris’s daughter and niece began showing symptoms, the next two girls to become afflicted by the fits were the niece of the town’s doctor and the daughter of the wealthiest man in town.

Perhaps the most infamous modern case of suspected conversion disorder occurred in 2012 in the upstate New York town of Le Roy, where a group of high school girls suffered from uncontrollable spasms and twitching. The fits began with a group of cheerleaders, before spreading to a “wider swath of the Le Roy high-school hierarchy,” as The New York Times Magazine thoroughly reported at the time.

Baker described the symptoms displayed by the girls in Le Roy in A Storm of Witchcraft:

Their symptoms ranged from subtle twitches to violent jerking of body parts and verbal outbursts. One girl woke up from a nap to find her “chin was jutting forward uncontrollably and her face was contracting into spasms.” She was still twitching several weeks later when her friend “awoke from a nap stuttering and then later started twitching, her arms flailing and head jerking.” Though beginning with one group of friends, the numbers of the afflicted rapidly grew outward. Soon there were twelve, next sixteen, and then eighteen suffering, in a community of just six hundred people. Even one teenage boy and a thirty six-year-old woman would show symptoms of distress.

Other reported cases in the U.S. dating back to the 1950s also disproportionately affected high school cheerleaders. And according to the Times, many of the afflicted girls in Le Roy had difficult or stressful home lives — from absent or estranged parents to teenage pregnancy to poverty.

The infamy the town received in the episode resulted in residents feeling even more isolated, with neighboring high schools canceling basketball games and concerns about plummeting business and real estate values.

In 2013, Massachusetts state health officials scrambled to investigate reports about an unexplained months-long case of repetitive “hiccups” by two-dozen students — mostly girls — at Essex Agricultural and Technical School in Danvers and nearby North Shore Technical High School in Middleton. The “sporadic vocal tics” were reported as “hiccups, grunts, and yelps,” Bartholomew wrote in a peer-reviewed scientific journal last year. Officials say most of the affected students were athletes.

The state’s environmental health chief medical officer ultimately ruled out all suspected causes as highly unlikely, except for “conversion or mass psychogenic factors.” However, those findings never made the final report released publicly in 2014.

A spokesman for the public health department said the purpose of the state’s review was to “look for potential environmental factors” contributing to the hiccups, rather than provide a diagnosis.

According to Bartholomew, there have been six total cases of the “motor-based” mass conversion disorder in the United States — all in schools, including Danvers — since 2000, compared to just four known cases in all of the 20th century.

“These motor-based cases are the same disorder as what happened in 1692 in Salem, but in a different cultural guise,” he said.

According to his research, motor-based cases have historically only been seen in oppressive situations, such as the “restrictive environs” of colonial Salem or present-day rural Africa.

The increasingly pervasive influence of social media is suspected to be a factor for the more recent increase in the United States and other Western countries, though the exact cause is still uncertain.

“It is not ‘all in their heads’ as those affected are feeling the symptoms, and they are not crazy,” Bartholomew said. “Most victims are normal, healthy people.”

Correction: A previous version of this article incorrectly identified a passage from Baker’s book, A Storm of Witchcraft, as referencing symptoms in Salem. It was referring to symptoms in Le Roy, New York.