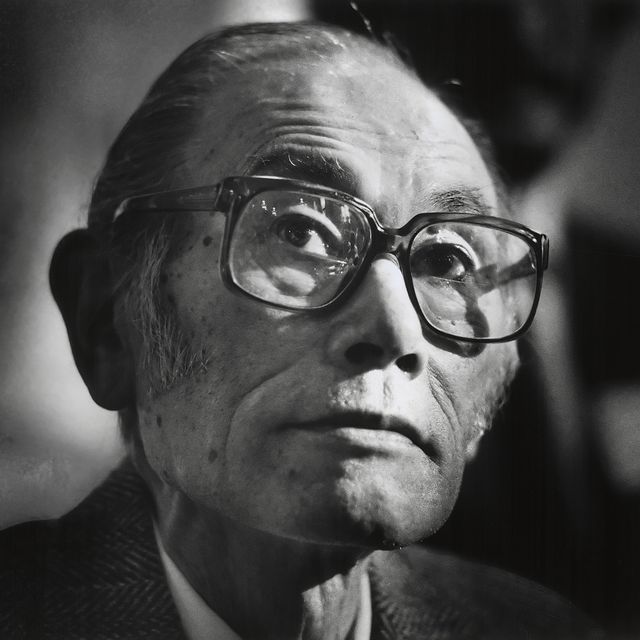

1919–2005

Quick Facts

ORIGINALLY: Toyosaburo Korematsu

BORN: January 30, 1919

DEATH: March 30, 2005

BIRTHPLACE: Oakland, California

Who Was Fred Korematsu?

Fred Korematsu believed that the United States' decision to send Japanese Americans into internment camps during World War II was racial discrimination and a violation of the Constitution. His case challenging the orders that resulted in his incarceration failed at the Supreme Court in 1944. In 1981, documents were discovered that showed the government had suppressed evidence in its arguments before the court, which led to the vacating of Korematsu's conviction in 1983. He then advocated for an apology and compensation for surviving internees. Korematsu died in 2005 at the age of 86.

Early Life

Toyosaburo Korematsu was born in Oakland, California, on January 30, 1919. His parents, Kakusaburo Korematsu and Kotsui Aoki, had immigrated from Japan and owned a plant nursery. He was the third of their four sons. Korematsu was nicknamed "Fred" in school.

Korematsu v. United States

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the subsequent entry of the United States into World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. Stating the need for"protection against espionage and against sabotage," it gave directions "to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent as he or the appropriate Military Commander may determine, from which any or all persons may be excluded." This resulted in the detention of around 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, even those who were U.S. citizens, as the military believed some were likely to aid Japan in the war.

Korematsu, a welder who lived in California, was ordered on May 3, 1942, to report to an assembly center for relocation to an internment camp. Though his family obeyed the directive, Korematsu did not. He instead adopted a fake identity and even underwent plastic surgery in an attempt to alter his appearance. Despite this, Korematsu was arrested on May 30, 1942, in San Leandro, California. He told authorities he'd planned to move away from California with his girlfriend.

While Korematsu was behind bars, a lawyer from the American Civil Liberties Union asked him to take part in a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of internment. Korematsu, who faced federal charges for not obeying a military relocation order, agreed. He was sent to an assembly center, which reunited him with his family, as his case began to make its way through the system. At his trial in September 1942, Korematsu, who'd attempted to enlist in the navy, proclaimed his loyalty as a citizen. He was still found guilty and received five years' probation.

Korematsu appealed his conviction, but it was upheld by a federal appeals court. The case was taken up by the Supreme Court and arguments were held in October 1944. The decision came down on December 18, 1944. In a 6-3 vote, the court ruled that Korematsu's conviction had been constitutional. The majority decided that the detention of Korematsu and others was not due to race, but rather"real military dangers." The opinion stated,"We could not reject the finding of the military authorities that it was impossible to bring about an immediate segregation of the disloyal from the loyal."

One of the three justices in the minority noted that internment was spurred by"the misinformation, half-truths and insinuations that for years have been directed against Japanese-Americans by people with racial and economic prejudices," and declared he was dissenting from"the legalization of racism."

Incarceration and Release

Korematsu spent his first months of detention at a horse racing track that served as an assembly center, where he was forced to live in a horse stall. He and his family were next transferred to the Topaz internment camp in Utah. This location was guarded by military police and surrounded by barbed wire. The six adults in his family had to squeeze into two dusty barracks rooms.

Other detainees and Korematsu's family disapproved of his decision to defy the government order. He later shared,"All of them turned their backs on me at that time because they thought I was a troublemaker." The girlfriend he'd hoped to marry, an Italian American, broke up with him, in part because she was subjected to police pressure.

In November 1942, Korematsu and other young camp residents were given permission to leave the Utah camp to work. He received indefinite leave from internment in January 1944, though he was not permitted to go back to the West Coast. Korematsu moved to Detroit, Michigan, after the war ended and the camps were shut down.

Conviction Overturned and Activism

Though Korematsu found work as a draftsman, his conviction hung over him and restricted job opportunities throughout his life. Four decades after his case had been decided, it came to light that the government had suppressed intelligence about the loyalty of Japanese Americans, showing they posed no security threat, in its presentation to the Supreme Court. Arguing that false evidence had deceived the court, a legal team, mostly made up of Japanese American attorneys, petitioned to get Korematsu's case reopened. On November 10, 1983, when Korematsu was 63, his conviction was overturned by a federal judge.

Korematsu lobbied for a 1988 bill that granted an apology to and compensation for those who'd been subjected to internment. President Bill Clinton awarded Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998.

In following years, in particular after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Korematsu tried to bring attention to other potential violations of civil liberties. He criticized parts of the Patriot Act and submitted a friend-of-the-court brief with the Supreme Court in support of prisoners held at Guantanamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba.

Personal Life

Korematsu married Kathryn Pearson in Michigan in 1946. They moved to California three years later. They had two children, Karen and Ken.

Korematsu's daughter stated in a 2012 interview that her father "felt responsible for the loss of his Supreme Court case in 1944 in regard to the rest of the Japanese and Japanese Americans that had been incarcerated, and he carried around the weight of that shame for almost 40 years." Because Korematsu found it too painful to discuss his case with his children, both learned about it in school instead.

Death

Korematsu passed away at the age of 86 on March 30, 2005, in Larkspur, California.

Legacy

The Fred T. Korematsu Institute provides materials to teach younger generations about Japanese American internment. Its executive director is Korematsu's daughter Karen.

The middle-grade biography Fred Korematsu Speaks Up, the biography Enduring Conviction: Fred Korematsu and His Quest for Justice and the documentary Of Civil Wrongs and Rights: The Fred Korematsu Story share Korematsu's life.

Multiple states and cities now recognize Korematsu's birthday as Fred Korematsu Day. It is the first day in the United States named in honor of an Asian American.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us!