Abstract

Purpose of Review

Alcohol is the most misused substance in the world. For people living with HIV (PLWH), alcohol misuse may impact ART adherence and viral suppression. This review of the most recently published alcohol intervention studies with PLWH examines how these studies considered gender in the samples, design, and analyses.

Recent Findings

Three searches were conducted initially, and 13 intervention studies fit our criteria with alcohol outcomes. In general, most studies did not consider gender and had used small samples, and few demonstrated significant efficacy/effectiveness outcomes. Five studies considered gender in their samples or analyses and/or were woman-focused with larger samples and demonstrated significant outcomes.

Summary

It is essential for women who misuse alcohol to not only be well represented in alcohol and HIV research but also for studies to consider the barriers to reaching them and their contextual demands and/or co-occurring issues that may affect participation and outcomes in intervention research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although the world had strived for the 90-90-90 treatment target by the end of 2020, we are not yet there, and the global push for the 95-95-95 treatment target may be temporarily out of reach given that the COVID-19 pandemic has impeded the world’s economies [1] and HIV treatment and prevention [2,3,4]. Additionally, alcohol, the most widely misused substance in the world [5], may be a key barrier to reaching this goal [6, 7], especially when coupled with challenges related to the COVID-19 pandemic [2,3,4].

Specifically, alcohol misuse may impact engagement and retention of people living with HIV (PLWH) in the HIV treatment cascade, which is critical to ending the HIV epidemic [8, 9]. Estimates suggest that 35 to 40% of PLWH may misuse alcohol [10]. Furthermore, myriad challenges often intersect with alcohol misuse that affects the health and well-being of PLWH [10]. If untreated, alcohol use disorder (AUD) can contribute to reduced adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), retention in HIV care [11, 12], and virologic response to ART, increasing the risk of forward transmission. AUD also ultimately increases mortality among PLWH [13]. Daily alcohol misuse is associated with reduced survival of 6 years among PLWH [13]. Consequently, the intersecting epidemics of alcohol misuse and HIV should be addressed together to help PLWH reach viral suppression and reduce transmission [14]. However, it may not be as simple as this.

Research is growing to address the intersection of alcohol misuse among PLWH [15]. The field has rapidly advanced and developed behavioral [15,16,17], pharmacological [18, 19], and biobehavioral interventions [20, 21] to reduce alcohol misuse among PLWH, with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) leading this effort [14]. Intervention approaches also have sought to reach key populations, including sexual minorities [22,23,24]. Intervention research, although nascent, also has extended its focus to cisgender women [25,26,27] and transgender women [25] living with HIV to address alcohol misuse.

However, this was not always the case, and the contemporary definition of gender is not binary (male-female), although most studies write in this fashion. For many years, women were excluded from or minimally involved in research [28]. For example, as recently as the 1980s, women were excluded from trials of HIV drugs [28]. Not until 1993 was the inclusion of women in National Institutes of Health research written into law [28, 29]. Importantly, alcohol misuse among women has recently gained greater recognition [30,31,32,33]. Including women in HIV and alcohol intervention research is critical because women’s physiological response to HIV and alcohol is different than men’s response; consequently, intervention effects may differ [34, 35]. NIAAA has highlighted the biological differences experienced by women when they drink and is in the process of reevaluating the recommended alcohol threshold for women [36].

This exclusionary trend also applies to pregnant populations, one of the most vulnerable populations to HIV, that historically have been excluded from alcohol research or addressed in research as a special population [37,38,39]. The need for more HIV and alcohol misuse research with this population is evident given the implication of prenatal drinking in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD) and other associated syndemic issues related to gender-based violence and ART adherence [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. NIAAA has been supporting FASD research for almost 50 years [48] among First Americans and in South Africa where heavy drinking is prominent [49,50,51,52]. Nonetheless, more research is needed.

The impact of alcohol misuse and HIV has greater adverse consequences for women compared with men [6, 34]. Hazardous alcohol use among women living with HIV (WLWH) is associated with HIV risk behaviors [53] and adverse health and HIV treatment outcomes [54], especially in economically underserved communities where heavy drinking may persist [54, 55]. Moderate drinking has been found to be associated with increased vaginal shredding among WLWH on ART [56]. Increased alcohol intake has been found to be associated with lower ART adherence [7]. Given the associations among alcohol misuse, vaginal shedding, and ART adherence for WLWH, moderate to severe alcohol use may increase risk of forward HIV transmission [56,57,58,59]. These findings illustrate the need for intervention trials to not only include women but also include them in sufficient numbers and to incorporate a gender lens for intervention approaches and analyses.

Given the importance of understanding what has worked in the most recent intervention research literature with PLWH who misuse alcohol, this review also highlights intervention studies focused on alcohol outcomes. However, essential to this review was our search with a gender lens in seeking sample proportions and analyses. Consequently, the core of this review is a search for gender interventions and why gender matters. Understanding the multidimensional issues that WLWH face and alcohol misuse is complex.

Methods

To ensure our review reached saturation of the available literature, multiple literature searches were conducted between December 2020 and February 2021 utilizing PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science scientific databases, as well as confirmatory checks in the NIH RePORTER and ClinicalTrials.gov. We included publications that met the following criteria: (1) published between 2018 and early February 2021; (2) reported or proposed alcohol outcomes for a randomized trial; (3) equal to or greater than 50% of the sample comprised PLWH; (4) the sample included cisgender or transgender women; and (5) written in English. We then reviewed the publications to determine whether there was an adequate sample size for a rigorous intervention trial [59, 60] and gender was accounted for in the study design (including intervention) and/or analysis (e.g., stratified analyses, gender as a moderator). Protocols were only included in this review if the proposed procedures considered women in the approach, intervention, design or outcomes, or if the intervention was developed for and about women and addressed alcohol as one of the proposed outcomes.

We conducted the search for publications in three phases. The initial search was conducted with a specific focus on seeking publications evaluating alcohol interventions for WLWH, including pregnant women; the second search expanded the criteria to alcohol interventions with PLWH; and the third search expanded the criteria to include a wide range of alcohol, drinking, and HIV-related terms to ensure that all appropriate publications were identified (see Appendix 1 for the entire search term list and criteria for each search).

After identifying published articles based on the search terms, research staff downloaded the results into an EndNote database and used a priori criteria to narrow the search using a categorical folder system. Although we made the search as comprehensive as possible, we did not search conference abstracts, theses, or dissertations; nor did we contact authors of unpublished articles. Our team reviewed the abstracts generated by the search. If the abstract indicated that the article might meet the specified criteria, it was reviewed in its entirety to ensure the inclusion criteria were met. Promising articles were then separated and presented to all of the present authors for their final review and approval for inclusion in this review.

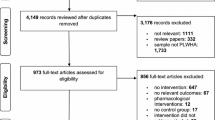

As shown in Fig. 1, the combined searches returned 8076 results. Of these, 7302 were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. A majority of the articles excluded during the abstract review did not focus on PLWH, were HIV prevention studies (and thus did not include a large percentage of PLWH), were cross-sectional, reported secondary data analysis from a prior trial, or did not report or propose alcohol outcomes. As a result of these searches, 13 intervention articles (8 non-gender and 5 gender-focused) and 3 protocols were included.

Results

Non-gender Studies

Eight of the identified studies evaluated the efficacy or effectiveness of interventions to reduce alcohol use among PLWH but did not use a gender lens in the design or analyses [21, 61,62,63,64,65,66,67]. The sample sizes of these studies ranged from 93 to 614, with 75% reporting sample sizes of fewer than 250. Of the 1897 participants across these 8 studies, only 7.9% were female or gender non-conforming, with 62.5% of the studies reporting more than 95% male participants. All the interventions evaluated incorporated motivational interviewing. Two interventions included cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) components [63, 67] and 3 interventions included medication-assisted treatment for alcohol use [21, 61, 62]. All interventions were delivered individually, with one intervention reporting additional optional group intervention components [63].

All studies used self-report alcohol assessments, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or the Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Six studies used the Timeline Followback (TLFB) to assess outcomes such as days of drinking, drinks per drinking day, and number of heavy drinking days in the past month [21, 61,62,63,64, 66]. Other self-report measures to assess alcohol-related outcomes included AUDIT and ASSIST. Also, 3 of the non-gender studies used phosphatidylethanol (PEth) biomarkers to assess alcohol abstinence [21, 61, 62]. Some studies included in this review also measured viral load using HIV RNA and the cut-off for viral suppression ranged from <20 to <50 copies/ml. Although most studies reported that participants reported reduced alcohol use at follow-up, only 3 studies demonstrated statistically significant intervention effects [63, 64, 67]. Go and colleagues conducted a trial comparing a culturally adapted motivational enhancement therapy and a brief alcohol intervention to standard of care among 440 PLWH in Thai Nguyen, Vietnam [63]. The findings from this study indicated that both intervention arms reported significantly greater abstinence and reductions in alcohol use and greater viral suppression at follow-up compared with participants in the standard of care arm. Madhombiro and colleagues demonstrated the efficacy of a combined motivational interviewing and CBT intervention to reduce AUDIT scores among 234 PLWH in Zimbabwe [67]. Lastly, Naar and colleagues reported the effectiveness of Health Choices, a motivational interviewing-based intervention, among 183 youth living with HIV that was implemented in and tested intervention delivery (home as compared with clinic settings) [64]. This study demonstrated that youth who received the intervention in a clinic setting were significantly more likely to maintain reductions in self-reported alcohol use and viral suppression (Table 1).

Gender Studies

Five of the identified studies evaluated the efficacy or effectiveness of interventions to reduce alcohol use among PLWH and used a gender lens in the design and/or analyses [26, 27, 68,69,70]. The sample sizes in this group of studies ranged from 194 to 641. Three of the 5 studies comprised all women, with 1 study sample reporting 46% women and 1 study sample reporting 51.5% women [26, 27, 69]. A variety of intervention approaches were represented, including pharmacotherapy for AUD, the information-motivation-behavior-skills framework, CBT, and feminist-based social cognitive theory.

All studies used self-report measures to assess alcohol use outcomes. The TLFB was the assessment used most. PEth was only used in 1 study as a measure of alcohol use. Additionally, all studies assessed some proportion of viral load among participants, with viral suppression cut-offs at <200 copies/ml in 2 studies and 1360 copies/ml in 1 study. All studies reported significant intervention effects for alcohol use outcomes. Cook and colleagues conducted a trial testing the efficacy and safety of oral naltrexone among 194 primarily African American WLWH and found that participants in the naltrexone intervention arm were significantly more likely to report lower levels of unhealthy drinking at short-term follow-up but not at the follow-up endpoint compared with participants in the placebo arm. HIV viral suppression was also significantly better for women who reduced drinking as compared with women who continued unhealthy alcohol use at 4 months [26]. Huis and colleagues investigated the effects of an information-motivation-behavior-skills intervention with personalized feedback and a brief counseling session compared with a health education leaflet on alcohol use among 560 PLWH in South Africa [68]. This study found that participants in the intervention and counseling arms had significantly greater reductions in AUDIT scores from baseline to follow-up compared with participants in the control arm. Additionally, when comparing men and women, men had a greater percentage reduction in AUDIT scores compared with women. Papas and colleagues tested the efficacy of a cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention to reduce alcohol use among 614 outpatients living with HIV with hazardous drinking enrolled at an HIV clinic in Eldoret, Kenya. They found significantly lower percentages of drinking days and drinks per drinking day in the CBT arm than the healthy life-styles educational intervention (HL) arm overall and at all study phases. Furthermore, adherence and competence scores in both the CBT and HL conditions did not differ significantly by gender [70].

Wechsberg and colleagues conducted a community-based cluster randomized trial evaluating the efficacy of a woman-focused HIV and substance use intervention to reduce substance use, including alcohol, and other risk behavior among 641 women who engaged in substance use [27]. Of the 641 women in the study, 317 were living with HIV and reported engaging in alcohol use. The overall trial demonstrated efficacy of the intervention to reduce heavy drinking and the number of days that participants drank in the past month. Chi-square tests of independence using dried blood spot samples indicated there was no difference in the proportion of participants who had nondetectable viral loads at 6-month follow-up (n=118; p=0.83). However, there was a significant difference at 12-month follow-up (n=172; p=0.01). Approximately 53% of participants in the Women’s Health CoOp Plus arm (n=50) had nondetectable viral loads compared with 47% of participants in the HIV counseling and testing arm (n=45) at 12-month follow-up. The results from a sensitivity analyses among 317 participants who were living with HIV and reported engaging in alcohol use revealed that the intervention also was efficacious among this subsample and significantly reduced the number of drinks per drinking day and number of days of alcohol use in the past month.

Lastly, Wechsberg and colleagues [69] conducted an implementation science hybrid modified stepped-wedge design implementing the Women’s Health CoOp (WHC) intervention in matched health departments and substance abuse treatment clinics with 480 WLWH over four cycles in Cape Town, South Africa. Compared with cycle 1, women in cycle 4 were significantly less likely to report AUD risk at 6-month follow-up. Additionally, compared with women in cycle 1, women in cycle 4 were significantly more likely to report taking ART at follow-up with over 90% adherence at 6-month follow-up. The likelihood of taking ART increased as women were enrolled in the later cycles and the risk of AUD decreased. The WHC intervention increased ART adherence and reduced alcohol use overall (Table 2).

Protocols for Ongoing Gender-Focused Studies

We also identified 3 protocols of ongoing studies currently considering gender in their evaluation of interventions that seek to reduce alcohol use among PLWH [71,72,73]. The 3 protocol papers reviewed include motivational interviewing, computer-based interventions, and the woman-focused intervention approaches. The planned sample sizes for these studies range from 60 to 200.

Two studies did not explicitly state a sample size goal for the recruitment of women, and participants are eligible regardless of gender. One study will recruit women exclusively. Two studies will use self-report alcohol measures (ASSIST or AUDIT) and 1 of these studies also will use urinalysis to assess alcohol outcomes. One study will exclusively use PEth and ethyl glucuronide (EtG) biomarker testing to assess alcohol outcomes. Two studies also will assess HIV outcomes using viral load, CD4+ cell count, and ART adherence measures (Table 3).

Discussion

So why is gender important in research? Women are the face of HIV globally because of gender norms and inequities [74]. Women face multiple contextual and structural barriers that may interfere with their ability to seek treatment for alcohol misuse and HIV care [55, 75, 76], let alone participate in research. Additionally, comprehensive gender-focused approaches are rare [77] and far too often childcare needs disproportionately hinder access to healthcare while also facing financial strain in less equitable employment as compared with men [76, 78].

Additionally, women who misuse alcohol may experience multiple challenges, including stigma [75]. Staff may have negative attitudes and lack person-centered care toward women who use alcohol and who are seeking treatment [75]. More recently, the ability to validate ART adherence and demonstrate reductions in viral load transmission has become a major component of intervention outcomes, and therefore the need to address alcohol as an interfering factor to ART adherence is critical [79,80,81]. However, the cost for conducting large trials may be a constraint.

For decades, studies focused on women who were pregnant and used alcohol and consequent fetal alcohol effects. In fact, these women have not been treated as a whole person, for example, by taking into account the fact that they often face violence from partners, especially during pregnancy [43, 82]. However, a recent study reviewing HIV medication adherence among women who are pregnant and living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa brought attention to the importance of supporting not only the woman but also her partner and the family in addressing fear, stigma, and discrimination around HIV [39], as ART initiation and adherence can be compromised by lack of support from partners and friends and their alcohol use [42].

A majority of the interventions were conducted domestically within the USA; however, interventions conducted internationally were culturally adapted to suit the environment and population [63, 67, 69, 70]. Regardless of location, most of the interventions contained a brief interview component. Studies conducted globally were more likely to identify significant reductions in alcohol consumption. Furthermore, the internationally focused studies were more likely to report higher levels of viral suppression and ART adherence, although few of the studies examined overall reported positive HIV outcomes. It is difficult to attribute these outcomes purely to whether a study was conducted internationally or domestically as many of the international studies had larger sample sizes—as they were conducted in areas with high HIV prevalence—thus they may have been more likely to report robust and significant outcomes. Lastly, the internationally focused interventions were also more likely to have a gender component or be gender-focused as compared with those conducted domestically.

It is a concern why some NIH- and NIAAA-supported studies have had such small participation of women relative to men. As gender intervention researchers, we believe there is much to do in addressing alcohol use, ART adherence, and other associated behavioral and psychological issues, including stigma and discrimination, other drug use, and gender-based violence. To better understand this, we reviewed numerous studies that address these intersectional issues and found that either they were HIV prevention studies, were not rigorous intervention studies, or did not have alcohol as an outcome variable. We acknowledge the importance of how motivational interviewing and a personalized approach can work to meet an individual where they are for engagement, but several of these approaches lacked gender sensitivity. Developing personalized action plans and empowering a woman to take action have been essential elements of the Women’s Health CoOp, a woman-focused intervention for over 25 years for reducing alcohol and other drug misuse and more recently increasing ART adherence [27, 69, 83, 84].

Nonetheless, how women are reached, whether an effort is made to oversample for adequate analyses, and sensitive consideration of their contextual needs and comorbid symptoms are essential to shaping a more just scientific response to the call for “why gender matters” More studies are needed with sexual minorities of women because they have higher rates of alcohol use, violence directed at them, HIV, and suicide [85,86,87]. Understanding the spectrum of gender is evolving as the world becomes more conscious and accepting.

The landscape of gender-focused interventions and applied research with women who misuse alcohol and other drugs, especially those living with HIV, requires not only sensitivity but also culturally congruent applications with the voice and involvement of the participants. As applied scientists over several decades, we have moved from the behavioral to biobehavioral, with treatment combinations and mixed methods to understand and conduct research that is meaningful and more impactful with many of the participants at the table, including peer advisory and community collaborative boards. However, there remains much to learn about what works best with each population.

Conclusion

In summary, alcohol misuse continues and FASD still is a public health issue [88,89,90]. Much can be done globally in intervention research with WLWH who misuse alcohol. Yet, intervention research cannot be everything to all. We also need to listen to women’s stories, consider gendered measures and stratified approaches, empower women be more educated about their HIV status, reduce barriers to ART and alcohol treatment, measure efficacy and effectiveness to know what will work, and identify mediators and moderators that affect change to ultimately understand what can be sustained in the real world [91]. Gender matters and women matter because they are mothers of the next generation.

Availability of Data and Material

The search terms used for this review are available in the supplementary material of this article.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ART:

-

antiretroviral retroviral therapy

- ASSIST:

-

Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test

- AUD:

-

alcohol use disorder

- AUDIT:

-

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

- CBT:

-

cognitive behavioral therapy

- EtG:

-

ethyl glucuronide

- FASD:

-

fetal alcohol spectrum disorders

- NIAAA:

-

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

- PLWH:

-

people living with HIV

- TLFB:

-

Timeline Followback

- WLWH:

-

women living with HIV

References

The World Bank. Global Economic Prospects. Washington, D.C. 2021.

Hogan AB, Jewell BL, Sherrard-Smith E, Vesga JF, Watson OJ, Whittaker C, et al. Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(9):e1132–e41. https://doi.org/10.25561/78670.

Jiang H, Zhou Y, Tang W. Maintaining HIV care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet HIV. 2020;7(5):e308–e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30105-3.

The Lancet. Maintaining the HIV response in a world shaped by COVID-19: Editorial. Elsevier; 2020396(10264). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32526-5.

Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S, Colledge S, Hickman M, Rehm J, et al. Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction. 2018;113(10):1905–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14234.

Kelso-Chichetto NE, Plankey M, Abraham AG, Ennis N, Chen X, Bolan R, et al. Association between alcohol consumption trajectories and clinical profiles among women and men living with HIV. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2018;44(1):85–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00952990.2017.1335317.

Lipira L, Rao D, Nevin PE, Kemp CG, Cohn SE, Turan JM, et al. Patterns of alcohol use and associated characteristics and HIV-related outcomes among a sample of African-American women living with HIV. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;206:107753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107753.

Azar MM, Springer SA, Meyer JP, Altice FL. A systematic review of the impact of alcohol use disorders on HIV treatment outcomes, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and health care utilization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112(3):178–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.014.

Vagenas P, Azar MM, Copenhaver MM, Springer SA, Molina PE, Altice FL. The impact of alcohol use and related disorders on the HIV continuum of care: a systematic review. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(4):421–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-015-0285-5.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Primary care of veterans with HIV. 2019.

Rooks-Peck CR, Adegbite AH, Wichser ME, Ramshaw R, Mullins MM, Higa D, et al. Mental health and retention in HIV care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018;37(6):574–85. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000606.

Hicks PL, Mulvey KP, Chander G, Fleishman JA, Josephs JS, Korthuis PT, et al. The impact of illicit drug use and substance abuse treatment on adherence to HAART. AIDS Care. 2007;19(9):1134–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120701351888.

Braithwaite RS, Conigliaro J, Roberts MS, Shechter S, Schaefer A, McGinnis K, et al. Estimating the impact of alcohol consumption on survival for HIV+ individuals. AIDS Care. 2007;19(4):459–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120601095734.

Bryant KJ, Nelson S, Braithwaite RS, Roach D. Integrating HIV/AIDS and alcohol research. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33(3):167–78.

Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Johnson BT, Carey MP. Behavioral interventions targeting alcohol use among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(2):126–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1886-3.

Brown JL, DeMartini KS, Sales JM, Swartzendruber AL, DiClemente RJ. Interventions to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected individuals: a review and critique of the literature. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(4):356–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-013-0174-8.

Madhombiro M, Musekiwa A, January J, Chingono A, Abas M, Seedat S. Psychological interventions for alcohol use disorders in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2019;8(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-019-1176-4.

Goh ET, Morgan MY. Pharmacotherapy for alcohol dependence–the why, the what and the wherefore. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(7):865–82.

Farhadian N, Moradi S, Zamanian MH, Farnia V, Rezaeian S, Farhadian M, et al. Effectiveness of naltrexone treatment for alcohol use disorders in HIV: a systematic review. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2020;15(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-020-00266-6

Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(17):2003–17. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.17.2003.

Edelman EJ, Maisto SA, Hansen NB, Cutter CJ, Dziura J, Deng Y, et al. Integrated stepped alcohol treatment for patients with HIV and alcohol use disorder: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(8):e509–e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30076-1.

Kahler CW, Pantalone DW, Mastroleo NR, Liu T, Bove G, Ramratnam B, et al. Motivational interviewing with personalized feedback to reduce alcohol use in HIV-infected men who have sex with men: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2018;86(8):645–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000322.

Wray TB, Kahler CW, Simpanen EM, Operario D. A preliminary randomized controlled trial of game plan, a web application to help men who have sex with men reduce their HIV risk and alcohol use. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(6):1668–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02396-w.

Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Santos J, Watt MH, Wilson PA, et al. The development and feasibility of a brief risk reduction intervention for newly HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men. J Community Psychol. 2011;39(6):717–32. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20463.

Zule W, Myers B, Carney T, Novak SP, McCormick K, Wechsberg WM. Alcohol and drug use outcomes among vulnerable women living with HIV: results from the Western Cape Women’s Health CoOp. AIDS Care. 2014;26(12):1494–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.933769.

Cook RL, Zhou Z, Miguez MJ, Quiros C, Espinoza L, Lewis JE, et al. Reduction in drinking was associated with improved clinical outcomes in women with HIV infection and unhealthy alcohol use: results from a randomized clinical trial of oral naltrexone versus placebo. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(8):1790–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.14130.

Wechsberg WM, Bonner CP, Zule WA, van der Horst C, Ndirangu J, Browne FA, et al. Addressing the nexus of risk: Biobehavioral outcomes from a cluster randomized trial of the Women’s Health CoOp Plus in Pretoria, South Africa. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;195:16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.10.036.

Food Drug Administration: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. General considerations for the clinical evaluation of drugs. Rockville, MD. 1977.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Ethical and Legal Issues Relating to the Inclusion of Women in Clinical Studies; Mastroianni AC FR, Federman D, editors,. Women and health research: ethical and legal issues of including women in clinical studies: Volume I. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 Public Law 103-43. 1994.

Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Kerridge BT, Ruan WJ, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911–23. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2161.

Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Keyes K. Alcohol use and binge drinking among U.S. men, pregnant and non-pregnant women ages 18–44: 2002–2017. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;205:107590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107590.

Bye EK, Moan IS. Trends in older adults’ alcohol use in Norway 1985–2019. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2020;37(5):444–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1455072520954325.

Slade T, Chapman C, Swift W, Keyes K, Tonks Z, Teesson M. Birth cohort trends in the global epidemiology of alcohol use and alcohol-related harms in men and women: systematic review and metaregression. BMJ Open. 2016;6(10). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011827.

Erol A, Karpyak VM. Sex and gender-related differences in alcohol use and its consequences: contemporary knowledge and future research considerations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.023.

Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O’Malley SS, Gastfriend DR, Pettinati HM, Silverman BL, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long-acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1617–25. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.13.1617.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Fact sheet: women and alcohol. 2020. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/women-and-alcohol. Accessed 02.08.2021.

May PA, Marais A-S, Gossage JP, Barnard R, Joubert B, Cloete M, et al. Case management reduces drinking during pregnancy among high risk women. Int J Alcohol Drug Res. 2013;2(3):61–70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13010076.

De Vries MM, Joubert B, Cloete M, Roux S, Baca BA, Hasken JM, et al. Indicated prevention of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in South Africa: effectiveness of case management. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(1):76. https://doi.org/10.7895/ijadr.v2i3.79.

Omonaiye O, Kusljic S, Nicholson P, Manias E. Medication adherence in pregnant women with human immunodeficiency virus receiving antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5651-y.

Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J, Burd L, Popova S. Global prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder among children and youth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(10):948–56. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1919.

Russell BS, Eaton LA, Petersen-Williams P. Intersecting epidemics among pregnant women: alcohol use, interpersonal violence, and HIV infection in South Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(1):103–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-012-0145-5.

Adeniyi OV, Ajayi AI, Ter Goon D, Owolabi EO, Eboh A, Lambert J. Factors affecting adherence to antiretroviral therapy among pregnant women in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):175. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3087-8.

Skagerstrom J, Chang G, Nilsen P. Predictors of drinking during pregnancy: a systematic review. J Women's Health. 2011;20(6):901–13. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2216.

Washio Y, Frederick J, Archibald A, Bertram N, Crowe JA. Community-initiated pilot program “My Baby’s Breath” to reduce prenatal alcohol use. Del Med J. 2017;89(2):46–51.

Jones HE, Berkman ND, Kline TL, Ellerson RM, Browne FA, Poulton W, et al. Initial feasibility of a woman-focused intervention for pregnant African-American women. Int J Pediatr. 2011;2011:389285–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/389285.

Jones HE, Myers B, O’Grady KE, Gebhardt S, Theron GB, Wechsberg WM. Initial feasibility and acceptability of a comprehensive intervention for methamphetamine-using pregnant women in South Africa. Psychiatry J. 2014;2014:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/929767.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Rethinking drinking: alcohol & your health: what are the different drinking levels? 2015. https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/how-much-is-too-much/is-your-drinking-pattern-risky/Drinking-Levels.aspx. Accessed 02.08.2021.

Clarren SK, Smith DW. The fetal alcohol syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1978;298(19):1063–7. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm197805112981906.

Hayden MR, Nelson MM. The fetal alcohol syndrome. S Afr Med J. 1978;54(14):571–4.

Mirtsou-Fidani V, Makedou K, Kourti M, Karakiulakis G. The fetal alcohol syndrome. S Afr Med J. 1997;15:84–90.

May PA, Hymbaugh KJ, Aase JM, Samet JM. Epidemiology of fetal alcohol syndrome among American Indians of the Southwest. Soc Biol. 1983;30(4):374–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.1983.9988551.

Aase JM. The fetal alcohol syndrome in American Indians: a high risk group. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1981;3(2):153–6.

Hutton HE, Lesko CR, Li X, Thompson CB, Lau B, Napravnik S, et al. Alcohol use patterns and subsequent sexual behaviors among women, men who have sex with men and men who have sex with women engaged in routine HIV care in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(6):1634–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2337-5.

Neblett RC, Hutton HE, Lau B, McCaul ME, Moore RD, Chander G. Alcohol consumption among HIV-infected women: impact on time to antiretroviral therapy and survival. J Women's Health. 2011;20(2):279–86. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2043.

Meyer JP, Springer SA, Altice FL. Substance abuse, violence, and HIV in women: a literature review of the syndemic. J Women's Health. 2011;20(7):991–1006. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2328.

Theall KP, Amedee A, Clark RA, Dumestre J, Kissinger P. Alcohol consumption and HIV-1 vaginal RNA shedding among women. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69(3):454–8. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2008.69.454.

Carter M. AIDSMap: Genital shedding of HIV fluctuates with a woman’s menstrual cycle. 2004. https://www.aidsmap.com/news/jun-2004/genital-shedding-hiv-fluctuates-womans-menstrual-cycle. Accessed 2/08/2021.

Carter M. AIDSMap: variations in genital shedding of HIV during menstrual cycle large enough to impact on risk of sexual transmission. 2013. https://www.aidsmap.com/news/feb-2013/variations-genital-shedding-hiv-during-menstrual-cycle-large-enough-impact-risk. Accessed 2.08.2021.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. PRS efficacy criteria for good-evidence risk reduction (RR) individual-level, group-level, and couple-level interventions (ILIs/GLIs/CPLs). 2014. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/dhap/prb/prs/efficacy/rr/criteria/HIV-RR-Efficacy-Best-ILI-GLI-CPLs.pdf.

Lyles CM, Kay LS, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Passin WF, Kim AS, et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):133–43. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2005.076182.

Edelman EJ, Maisto SA, Hansen NB, Cutter CJ, Dziura J, Deng Y, et al. Integrated stepped alcohol treatment for patients with HIV and at-risk alcohol use: a randomized trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2020;15(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-020-00200-y.

Edelman EJ, Maisto SA, Hansen NB, Cutter CJ, Dziura J, Deng Y, et al. Integrated stepped alcohol treatment for patients with HIV and liver disease: a randomized trial. J Subst Abus Treat. 2019;106:97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.08.007.

Go VF, Hutton HE, Ha TV, Chander G, Latkin CA, Mai NV, et al. Effect of 2 integrated interventions on alcohol abstinence and viral suppression among Vietnamese adults with hazardous alcohol use and HIV: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2017115. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17115.

Naar S, Robles G, MacDonell KK, Dinaj-Koci V, Simpson KN, Lam P, et al. Comparative effectiveness of community-based vs clinic-based Healthy Choices Motivational Intervention to improve health behaviors among youth living with HIV: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2014650. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17115.

Satre DD, Leibowitz AS, Leyden W, Catz SL, Hare CB, Jang H, et al. Interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use among primary care patients with HIV: the health and motivation randomized clinical trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(10):2054–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05065-9.

Stein MD, Herman DS, Kim HN, Howell A, Lambert A, Madden S, et al. A randomized trial comparing brief advice and motivational interviewing for persons with HIV–HCV co-infection who drink alcohol. AIDS Behav. 2020:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03062-2.

Madhombiro M, Kidd M, Dube B, Dube M, Mutsvuke W, Muronzie T, et al. Effectiveness of a psychological intervention delivered by general nurses for alcohol use disorders in people living with HIV in Zimbabwe: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(12):e25641. https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25641.

Huis in’t Veld D, Ensoy-Musoro C, Pengpid S, Peltzer K, Colebunders R. The efficacy of a brief intervention to reduce alcohol use in persons with HIV in South Africa, a randomized clinical trial. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0220799. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220799.

Wechsberg WM, Browne FA, Ndirangu J, Bonner CP, Kline TL, Gichane M, et al. Outcomes of Implementing in the real world the Women's Health CoOp intervention in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03251-7.

Papas RK, Gakinya BN, Mwaniki MM, Lee H, Keter AK, Martino S, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a group cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce alcohol use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected outpatients in western Kenya. Addiction. 2021;116(2):305–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15112.

DiClemente RJ, Brown JL, Capasso A, Revzina N, Sales JM, Boeva E, et al. Computer-based alcohol reduction intervention for alcohol-using HIV/HCV co-infected Russian women in clinical care: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2021;22(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-45325/v1.

Kane JC, Sharma A, Murray LK, Chander G, Kanguya T, Lasater ME, et al. Common Elements Treatment Approach (CETA) for unhealthy alcohol use among persons with HIV in Zambia: study protocol of the ZCAP randomized controlled trial. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;12:100278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100278.

Magidson JF, Joska JA, Myers B, Belus JM, Regenauer KS, Andersen LS, et al. Project Khanya: a randomized, hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial of a peer-delivered behavioral intervention for ART adherence and substance use in Cape Town, South Africa. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-020-00004-w.

Wechsberg WM, Myers B, Reed E, Carney T, Emanuel AN, Browne FA. Substance use, gender inequity, violence and sexual risk among couples in Cape Town. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(10):1221–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.815366.

Howard BN, Van Dorn R, Myers BJ, Zule WA, Browne FA, Carney T, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing an evidence-based woman-focused intervention in South African health services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):746. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2669-2.

Myers B, Carney T, Wechsberg WM. “Not on the agenda”: a qualitative study of influences on health services use among poor young women who use drugs in Cape Town, South Africa. Int J Drug Policy. 2016;30:52–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.12.019.

Meyer JP, Isaacs K, El-Shahawy O, Burlew AK, Wechsberg W. Research on women with substance use disorders: reviewing progress and developing a research and implementation roadmap. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:158–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.017.

Myers B, Louw J, Pasche S. Gender differences in barriers to alcohol and other drug treatment in Cape Town, South Africa. Afr J Psychiatry. 2011;14(2):146–53. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v14i2.7.

Hu X, Harman J, Winterstein AG, Zhong Y, Wheeler AL, Taylor TN, et al. Utilization of alcohol treatment among HIV-positive women with hazardous drinking. J Subst Abus Treat. 2016;64:55–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.011.

Myers B, Fakier N, Louw J. Stigma, treatment beliefs, and substance abuse treatment use in historically disadvantaged communities. Afr J Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajpsy.v12i3.48497.

McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Fokas KF. Treatment interventions for women with alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Res Health. 2020;40(2). https://doi.org/10.35946/arcr.v40.2.08.

Wechsberg WM, Browne FA, Poulton W, Ellerson RM, Simons-Rudolph A, Haller D. Adapting an evidence-based HIV prevention intervention for pregnant African-American women in substance abuse treatment. Subst Abus Rehabil. 2011;2(1):35–42. https://doi.org/10.2147/SAR.S16370.

Wechsberg WM. Adapting HIV interventions for women substance abusers in international settings: lessons for the future. J Drug Issues. 2009;39(1):237–43.

Wechsberg WM, Browne FA, Ellerson RM, Zule WA. Adapting the evidence-based Women’s CoOp intervention to prevent human immunodeficiency virus infection in North Carolina and international settings. N C Med J. 2010;71(5):477–81.

Hughes TL, Eliason M. Substance use and abuse in lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. J Prim Prev. 2002;22(3):263–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025424.

Hughes TL, Veldhuis CB, Drabble LA, Wilsnack SC. Research on alcohol and other drug (AOD) use among sexual minority women: a global scoping review. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0229869. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229869.

Hughes, TL, Wilsnack SC, Kantor LW. The influence of gender and sexual orientation on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems: toward a global perspective. Alcohol Res Health. 2016;38(1):121-32.

Popova S, Lange S, Probst C, Gmel G, Rehm J. Global prevalence of alcohol use and binge drinking during pregnancy, and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;96(2):237–40. https://doi.org/10.1139/bcb-2017-0077.

Olivier L, Curfs L, Viljoen D. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: prevalence rates in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2016;106(6):S103. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i6.11009.

Wynn A, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Davis E, le Roux I, Almirol E, O’Connor M, et al. Identifying fetal alcohol spectrum disorder among South African children at aged 1 and 5 years. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;217:108266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108266.

Gichane MW, Wechsberg WM, Ndirangu J, Browne FA, Bonner CP, Grimwood A, et al. Implementation science outcomes of a gender-focused HIV and alcohol risk-reduction intervention in usual-care settings in South Africa. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;215:108206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108206.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of all the authors whose work we included in this review and our editor, Jeffrey Novey.

Funding

Support for this review was provided by the RTI Global Gender Center and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01AA022882.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WMW provided the overall scientific direction for the review, significantly contributed to the writing, and finalized the manuscript. FAB substantially contributed to the writing of the manuscript. CPB significantly contributed to the writing of the methods and one subanalysis of a study in the article. YW conducted the search for interventions focused on pregnant women living with HIV and substantially contributed to the development of all components of the manuscript. BNH conducted the search for interventions focused on women living with HIV and contributed to the writing of the methods. IvdD conducted the search for interventions focused on women living with HIV and contributed to the development of the methods. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Behavioral-Bio-Medical Interface

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 13 kb).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wechsberg, W.M., Browne, F.A., Bonner, C.P. et al. Current Interventions for People Living with HIV Who Use Alcohol: Why Gender Matters. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 18, 351–364 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-021-00558-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-021-00558-x