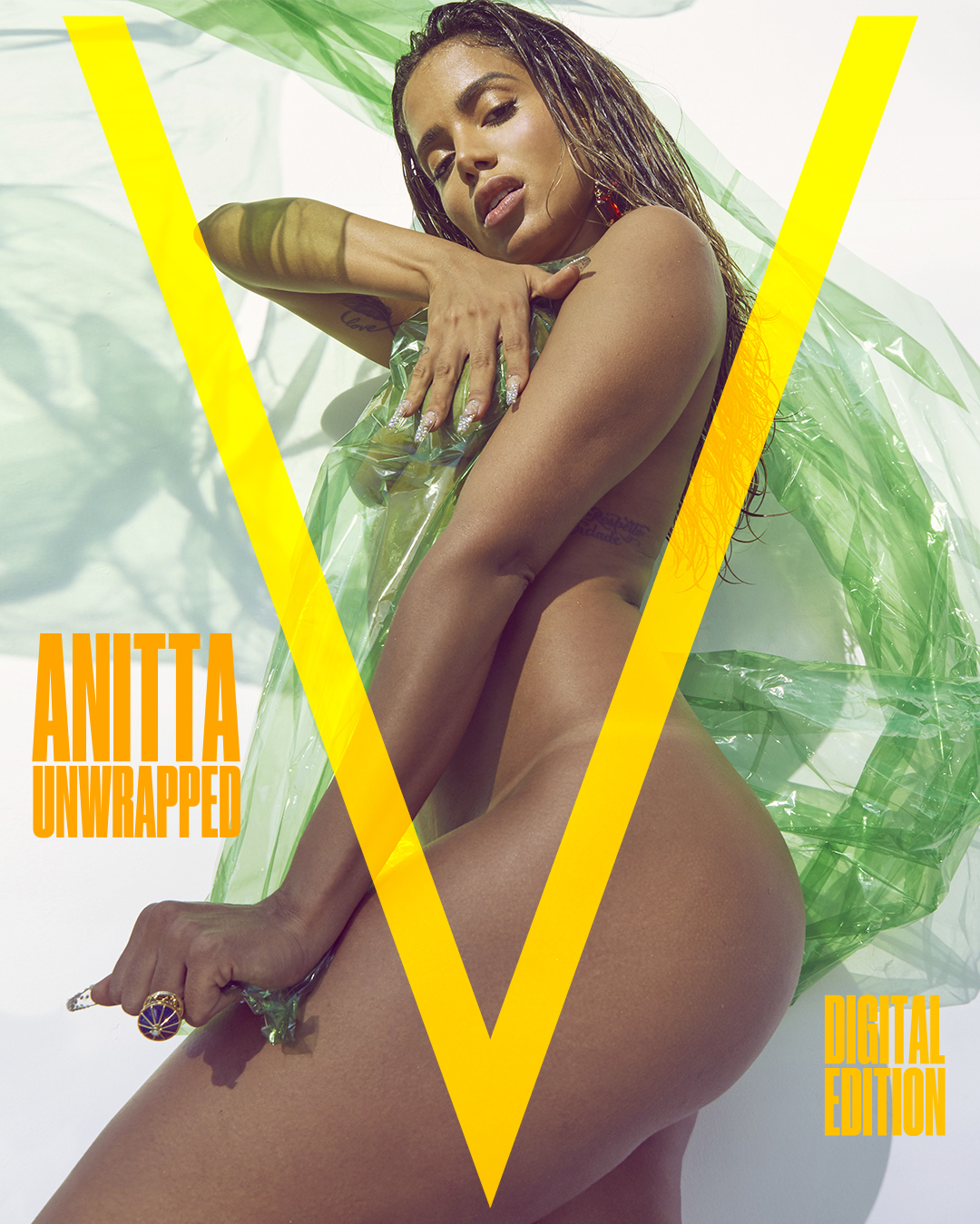

For many pop music fans in America, the first embers of Anitta’s global takeover came ashore in 2019. That year, Madonna’s Madame X album dropped, and with it an all-Portugese banger called “Faz Gostoso.” A cover of Portuguese artist Blaya’s multi-platinum hit, Madonna’s version featured a different mononymic singer: Anitta, who, if you don’t know by now, is something like the Madonna of Brazil.

In her relatively swift rise since her 2010 debut in Brazil, Anitta—like Madonna before her—has defied everything from musical conventions to censorious forces. A product of Rio’s favelas—that is, the city’s most poor and disenfranchised sectors—the singer’s Brazilian-funk style has been subject to bans by conservative Brazilian lawmakers as recently as 2017.

Those obstacles only make her unstoppable momentum all the more gratifying. Having recently inked a high-profile deal with Warner Music US, the singer is gearing up to release a new album—a triumphant blend of global influences and undeniable danceability, as its newly dropped flagship single, “Tócame,” proves. Here, the 27-year-old singer speaks with EDM pied piper Diplo, revealing characteristic fervor for everything from public health awareness to toppling the patriarchy.

See below for the full interview and listen to Anitta’s hit new single “Tócame” featuring Arcangel & De La Ghetto.

DIPLO Anitta, you there? How are you?

ANITTA Hi, Wes! Hi! I’m good. How are you?

D The last time we saw each other was in Salvador, in your truck [at Carnival]. did you think that was going to be the last party of the year? Because that’s what it was.

A You know, I didn’t realize! But I partied so much.

D You don’t party all the time, but you were partying… For people who don’t know about Carnival, it’s a pretty big deal [in Brazil], and Anitta has her own truck. And [you] perform for, like, seven hours straight. You’re literally on stage for seven hours—and drinking! You had a gin and tonic the whole time. Like, you’re just drunk. And that’s a long-ass performance. How do you do that?

A Carnival in Brazil is like ten days of crazy, non-stop partying. We build a stage on the top of a truck, and then we go through the city, singing, and people follow the truck. I like to have fun while I’m doing it—fun and work at the same time.

It’s like a marathon; you need to use your voice so much. And on the last day, I had a party at my house only for the workers—only for people who were working at Carnival. We partied all day at my house [laughs].

D I remember we worked on a song together right before Carnival. I hit you up, like, a month before [we were going to release it].

A With “Rave de Favela,” we wanted it to be the Carnival song that year. I said, “Okay, if we release this song a week before Carnival, then it will be number one.” And that’s what happened! The song was everywhere. It was a fucking hit, everywhere. It was amazing.

D You’re the only person I could count on [to work like that].

A Same to you! They just believe whatever I say, here in Brazil. But outside of Brazil? You’re the only person who would say, “Yeah, let’s go.”

D People don’t realize, like, you actually do everything. I work with artists who are like, “I don’t know… I did a show four days ago.” And I’m like, “Anitta will do fifty shows!” And then shoot a video, looking hotter than anybody. Not sleep, go to the gym the next morning, and then fly back to Brazil for a party. I use you as an excuse to work harder…Another Anitta story I have is [when you] flew from Brazil to Morocco for one day, to shoot a video. Also fucking crazy.

A [laughs] Remember, I passed out?

D You died. You were in the craziest clothes—like full Spandex. You had to walk a mile to the shot, in 115-degree heat, and then dance in the desert. I remember I walked backstage and they had covered you in ice and you weren’t moving. I thought you were dead. I was like, “Damn, we killed her…I hope the video does well, because she’s dead.” [laughs] Can you tell us a little about that experience?

A [laughs] It was so hot, and they put me in this plastic bodysuit outfit! But then I came back to life and I kept shooting the video.

D You’re spontaneous. That’s what I love about Brazil. I’ve been going to Rio for many years. And you’re that kind of person. You are like Rio as a human being, I feel like.

A [laughs] Oh my God, I love this! Oh my God, I love this. Oh my God, I love this. Please, V Magazine, put this [in]! “I’m like Rio as a human being!” I love it.

D Yeah, if Rio could be a person, it’s you. Can you explain why you are the way you are? Like, what is it that created you? Is it from being from Rio?

A I mean, I think that it’s because I came from a part of Rio… I had a simple life—my family wasn’t a “money” family. So I needed to be creative to [get] things done. And also, with this party vibe that the country, and especially Rio, has… Being born in the middle of this good mess made me want to create opportunities for myself. Whatever is necessary to do to reach my goal, I just do it. When I was poor, I didn’t have the opportunities or structure to do what I wanted. So I needed to create my own structure. That’s what I think.

There are different Rios. There’s a Rio for fancy, rich people, this “A” class. And then there is the city of the other people, and people who know the “B” places.

D From an outsider’s perspective, it felt like those sides don’t talk to each other. But you’re one of the first people I met who seemed to really understand both sides.

A My family always taught me the importance of studying. Even though the country doesn’t give us that much structure or opportunities for [education], I was always online. I learned a lot from the internet. And then, I was always a curious person about music; I grew up listening to everything. Like, the fancy music and the hood music. So, if I go to a favela party, I know how to behave because I came from this place. And if I go to the fancy part [of town], I know how to switch. There are two people—two Anittas inside me.

[It also helps] to speak [multiple languages]: I speak Spanish, English, Portuguese, a little Italian… And now I’m taking advantage of the quarantine to learn French. So… [laughs] My mind’s going to blow up.

D I think that people don’t realize how [multifaceted] the music scene in Brazil is. It’s a lot more progressive than America. With clubs in Brazil, it’s not a gay or straight club—it’s literally a unisex club. Everything is gay, straight, black, white, woman, man…

A Yeah, Everyone is just mixed. We like to mix things.

D [But at the same time], you have a president that’s just like Trump in a lot of ways…

A Oh, worse. Probably worse.

D I don’t know if you want to talk about politics, but [Brazil seems like] a conservative place on the outside, but inside, it’s very, very fluid and beautiful. Can you explain a bit about what it’s like being a woman artist in Brazil?

A I have no filter. Whoever talks to me, I’m just honest. So I think that this brings even more prejudice for myself because people expect you, as a woman, they have expectations like: ‘Okay. So you’re going to be like this. You’re going to have a boyfriend. You’re going to be every, every day you got to behave like that.’ And I’m like, ‘I don’t want to be like that. I just want to do whatever I want to do.’ Why can men do whatever they want to do, and women can not?

Now, it’s good, because other women [artists] have told me that I’ve helped [make things] less difficult for them. ‘Cause I’ve already caught all those rocks that people were throwing at me. I like to push new [artists], you know? If someone is blowing up, or is super talented, I know that if I give just a little push, they’re going to go even farther. I think you do this, too.

D Yeah, we’re the same in that way. I feel like Brazil is like America, in some ways: a mashup of all different people. I’ve always been obsessed with Brazil, and you’re the first person who really explained the beauty of it. You’re like an encyclopedia to me, and I really appreciate all you’ve done for Brazil[ian music], globally.

A Oh my God, I’m feeling so special right now!

D You’re like the new generation. You’re really good friends with J Balvin, too. The two of you are the most amazing ambassadors of music, and you’re so fucking cool and humble. The bigger you get, the more humble you guys are.

A I think it’s important to never forget those kinds of things. We never know how life is going to go.

D You’ve really made [funk music] mainstream, but you still didn’t make it pop. You made it yourself. You just made it bigger. Can you explain the prejudices about funk music, and how that has changed?

A So it’s pretty similar to hip-hop’s history, in the U.S. The rhythm [of funk] is an urban rhythm. In the beginning, the upper classes [in Brazil] were super against funk; If you liked funk, you were considered a freak—a bad person, almost. So the radio, the clubs in the city—they didn’t play the rhythm.

D And then fast-forward ten years…You go to a party on a rooftop and it’s like [everyone from] models to, fifty-year-old ladies—they’re all singing the lyrics to Anitta!

A You know, I needed to go through a lot of bad situations to break this prejudice: people that underestimated me my talent, or my intelligence, whatever… Just because of the rhythm. That used to make me feel so bad. I was, like, “Man, I need to do something to change this.” So I started to go hard and study and put myself in classes to understand the culture of the other side of the country, which I’d [never encountered] because I didn’t have money. I think that’s how I got this conversation [started].

D You’ve conquered Brazil… You’ve lifted the ceiling so high. There’s no door? You’re going to fucking break through the wall… So, what’s happening [now]? What’s happening? Tell me about the new music.”

A We are cooking new music! I mean, we just finished cooking all of it. We’re bringing some things from Brazil, so people in Brazil are gonna feel they’re represented somehow. It’s like half-English, half-Spanish, with a few words of Portugese [thrown in].

It’s me, introducing Brazilian culture to the world. This album is amazing. I feel it’s the best thing I’ve ever done. I just listen to it every day.

I did one of the videos before the quarantine, here in Brazil. The others we are going to shoot when [quarantine] is over. Which… will hopefully be soon?

D Yeah. I mean, I see the news… Brazil has been one of the hardest-hit places. It’s up there with America. Am I reading the right thing?

A I have a privileged point [of view], because of who I am. But many people [here] are suffering a lot. The president doesn’t support anything or anybody. He has no respect for the victims. I’m trying to find ways to educate people on my Instagram. Every Friday, I do political classes to help my audience understand what is going on in our country.

D I hope [it helps]. I don’t want Carnival to be canceled—it’s my favorite thing ever!

A Yeah! I’m like, “We gotta get this done because Carnival needs to happen!”

D That’s the way to defeat coronavirus: Carnival. That’s the way to beat it.

A The party moves everyone, right?

Discover More