The American health-care system is a vast, dilapidated mansion with stairways that lead to nowhere, floorboards full of termites, walls that bleed asbestos, shattered windows, a broken furnace, flooded basement, and the unfriendliest of ghosts.

In other words, it is a hellacious, irrational structure that would be cheaper to tear down and rebuild than renovate, repair, or even maintain.

But the existing structure works well for the exterminator, space-heater, and ghostbuster industries, all of which have strong lobbies (and would suffer a sharp decline in profitability if America transitioned to a single-heater mansion that was ghost-free at the point of service). And since millions of ordinary Americans don’t even have access to the mansion, those who are privileged enough to enjoy its modest protections — especially those who’ve secured a relatively dry and warm spot within the crumbling structure — tend to express satisfaction with the status quo in opinion surveys. So, when voters are told that they can have cheaper, more comprehensive protection from a brand-new mansion — so long as they accept a modest increase in property taxes, which would be fully offset by savings on utilities and maintenance — many evince skepticism. And once Big Ghostbuster starts airing fear-mongering ads about how tearing down the existing structure will turn U.S. into Venezuela, that skepticism is liable to harden into opposition.

This is how I described the political economy of American health care back in April. And I think the extended metaphor still does a decent job of illustrating how our status-quo insurance system has managed to sustain itself politically, even as it fails the American public profoundly. But a new study from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) suggests that conditions in our figurative mansion are deteriorating so rapidly — and the hospitable rooms growing so few and far between — that the politics of structural change may be undergoing a transformation.

As indicated above, the primary obstacle to rebuilding our ramshackle health-care system is the immense power of the industries and interest groups that have monetized its rot. But historically, public opinion has posed its own discrete challenges. Voters often display a strong sense of loss aversion, valuing the preservation of what they have over the uncertain promise of something better. And in the domain of health care — where the stakes of losing what one has (if one is privileged enough to have coverage in the general vicinity of “affordable”) are potentially life and death — this tendency has been especially acute.

A distinct but related feature of U.S. public opinion is that it tends to be “thermostatic,” moving left when there’s a Republican in the White House, then right when a Democrat moves back in. Once again, this general tendency is particularly strong on the issue of health care: In 2007, 69 percent of voters told Gallup that it was the federal government’s responsibility to ensure all Americans have health-care coverage; by the second year of Barack Obama’s presidency, that figure was down to 47 percent. Then Donald Trump’s election made the concept of universal health care majoritarian again.

It’s possible that this pattern is informed by the welfare chauvinism of some white voters (i.e., there may be some GOP voters whose comfort with big government ebbs and flows, depending on whether the party of white identity politics controls its levers). But whatever its origins, the phenomenon has been a perennial source of difficulty for progressive reformers, especially those who demand answers commensurate with the scale of the system’s problems: With the public already predisposed toward loss aversion and ideological fickleness, the health-care industry (and its ad-makers) have had little trouble killing off any reform that dared to threaten its share of GDP.

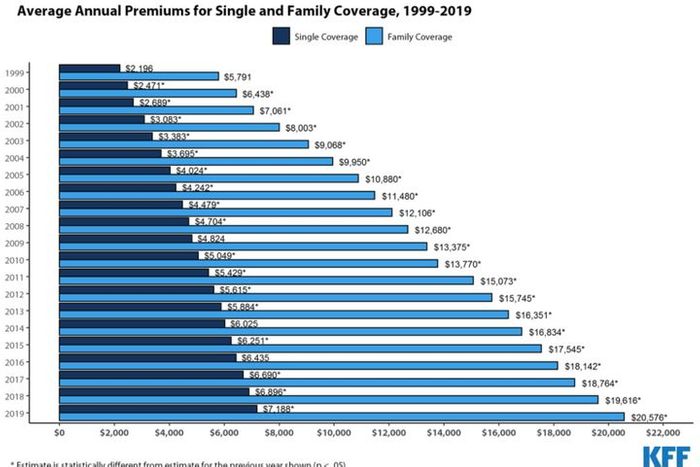

For these reasons, a lot of health-care punditry presumes that the public’s appetite for Medicare for All — or even a Medicare buy-in — will swiftly decline once Democrats have the opportunity to actually implement it. And that scenario remains plausible. But there’s increasing reason to believe that “next time will be different” — because with each passing year, those loss-averse voters with employer-provided insurance have less and less to lose: According to KFF’s latest survey, the average annual premium for a job-based, family health-insurance plan is now $20,756 — 54 percent higher than it was just ten years ago. And the price of such plans is rising even faster for their actual beneficiaries, as employers offload rising health-care costs onto workers: Since 2009, the average premium paid by employees for a family plan has jumped by 71 percent to $6,015.

Among workers themselves, the distribution of the growing burden is deeply regressive. Since high-wage workers have more bargaining power than low-wage ones, firms force far more cost-sharing on the latter than the former. As a result, an increasing number of low-wage workers are forgoing employer-provided coverage. As Bloomberg notes:

In firms where more than 35% of employees earn less than $25,000 a year, workers would have to contribute more than $7,000 for a family health plan … Only one-third of employees at such firms are on their employer’s health plans, compared with 63% at higher-wage firms …

Some employers have opted to keep premiums affordable by diverting rising costs into higher deductibles, a policy that effectively takes from sick workers to give to healthy ones. Which goes over well with the median worker — right up until he or she moves from that second category to the first.

Critically, even if your employer does shoulder a hefty portion of your health-care costs, the existence of that new expense on its balance sheet may ultimately take money from your pocket. The more cash the average business has to fork over to the health-care sector, the less it can afford to spend on wages and other benefits. This reality is likely among the many reasons that U.S. wage growth has been so tepid in recent decades.

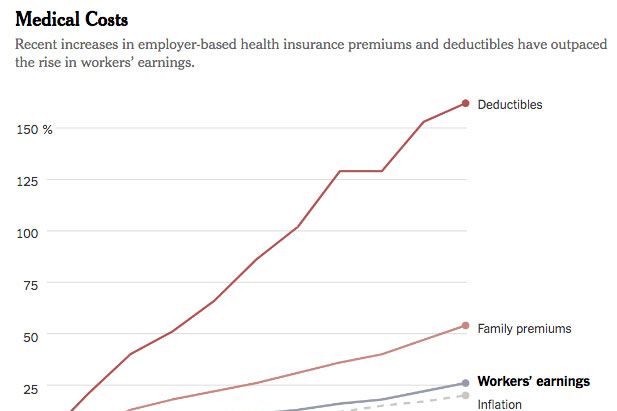

A chart from New York Times weaves these disparate trends into a unified portrait of abject policy failure:

It is true that, for most of the decade documented here, American public opinion on health-care policy actually trended rightward. One could attribute that fact to the Affordable Care Act’s peculiar failures, or to thermostatic public opinion. Either way, it is an argument against the assumption that worsening objective conditions will necessarily build public support for radical reform.

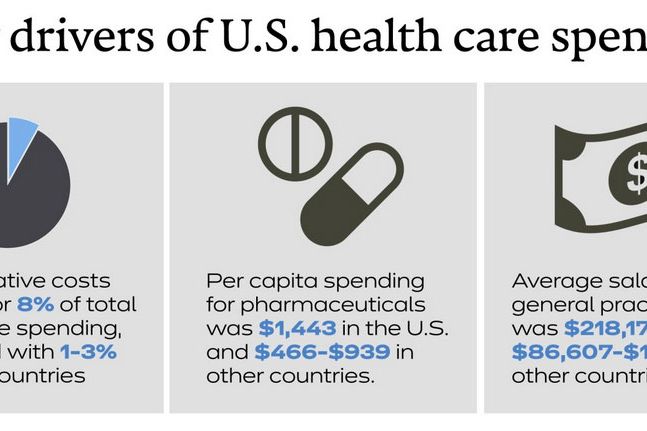

Still, it’s hard not to think that there will eventually be a breaking point. Absent massive policy changes, things are going to get worse before they get better. As the boomer generation ages, it will consume more and more health-care services, thereby driving up their price. Meanwhile, the burgeoning demand for drugs that ease the burdens of senescence is leading Big Pharma to roll out exorbitantly expensive new medicines. These demographic-driven cost pressures aren’t unique to the U.S. But America’s uniquely weak cost controls make them harder to absorb. Under our existing system, the U.S. spends several times more than similar nations on health-care administration, pharmaceuticals, and physicians’ salaries. In return, Americans enjoy the 29th best health-care system in the world (just behind the Czech Republic’s), according to the Lancet.

Low-wage workers still bear the brunt of this boondoggle. But as the costs of sustaining an extractive health-care sector inexorably rise, more and more politically empowered, upper-middle-class Americans will be unable to insulate themselves from the burden. This won’t automatically turn affluent moderates into single-payer supporters. In fact, a sense of scarcity could potentially undermine social solidarity and thus support for universal coverage. But a continuation of present trends will lead influential constituencies to demand cost controls on the health-care sector with increasing vehemence. A Times interview with a bagel-shop owner in Utica, New York, named Anne Wadsworth is illustrative of where upper-middle-class health-care politics is trending.

“I was all on board for Obamacare,” she said, but it proved not to be “a long-term solution. It doesn’t lower the costs for people.”

Ms. Wadsworth is wary of the sweeping plans now proposed by the Democratic presidential candidates, which she worries will become a political football, like the Affordable Care Act, and fail to address the underlying issues.

“I just think health care costs need to go down,” she said.

Whether progressives can persuade voters like Wadsworth that only “sweeping plans” can deliver the cost-savings she seeks — by eliminating redundant insurance bureaucracies, rationalizing hospital budgets, and bringing U.S. physician salaries into closer alignment with international standards — is unclear. But that task should become a bit easier, as the roof above their heads starts caving in.