With amazing speed, ending mass incarceration has become a priority not only for leftists but also for centrists and even for some on the right. Jared Kushner recently classed prisoners with other “forgotten men and women” championed by Donald Trump. But none of the reforms on the table will actually end mass incarceration. Even if tomorrow we release every non-violent drug offender, every ageing prisoner and everyone who is in jail solely because they can’t make their bail – and we should do those things – the United States would still have an incarceration rate an order of magnitude higher than its peer nations.

To end mass incarceration, we need prison abolition. Impossible? Not so long ago, prison abolition felt almost inevitable.

Juan G Morales belonged to the 1970s crush of incarcerated men and women who asked the courts to ease the harshness of prison life. Morales was incarcerated in the state of Wisconsin, and his jailers were not allowing him to exchange letters with his lover. He brought an action in federal court against the state in order for his right to correspondence to be restored. His case came to Judge James E Doyle, father to a future governor.

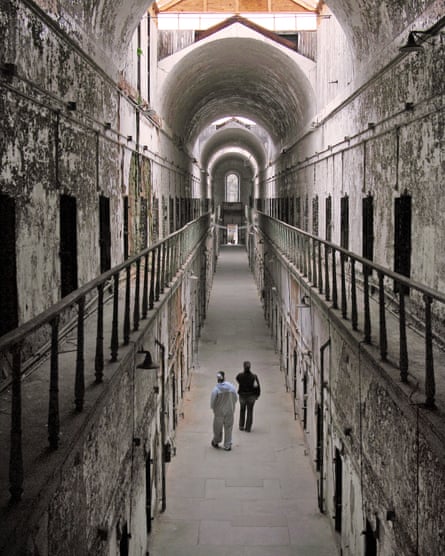

Doyle sided with Morales, and the language he employed says much about how the prison system was viewed by mainstream America at that time: “I am persuaded that the institution of prison probably must end. In many respects it is as intolerable within the United States as was the institution of slavery, equally brutalizing to all involved, equally toxic to the social system, equally subversive of the brotherhood of man, even more costly by some standards, and probably less rational.”

In the years after Doyle wrote, the prison population soared, imprisonment became a predominant feature of American life, and a world without prisons became even more difficult to imagine. Yet Doyle’s words reflected a very real sense common to the early 1970s that the end of the prison could be quite near. The Norwegian criminologist and prison abolitionist Thomas Mathiesen describes this historical moment – not only in the US, but across the Atlantic as well – as the only time in the history of the prison when prison abolition was a real possibility. We are reaching another such moment, and we ought to learn from what went wrong nearly a half-century ago. Among the reasons the protean movement to abolish prisons fizzled was its refusal to speak in plainly moral terms. In foregrounding pragmatic reforms, 1970s prison reformers turned away from the rich abolitionist heritage and failed to generate the force necessary for effecting radical social change.

Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow has done much of late to introduce the massive scale of the injustices involved in the prison system to a mainstream audience, but from the late 1960s to the early 1970s, there were any number of such publication events: Karl Menninger’s The Crime of Punishment (1968), Nigel Walker’s Sentencing in Rational Society (1969), Richard Harris’s The Fear of Crime (1969), former attorney general Ramsey Clark’s Crime in America (1971), and Jessica Mitford’s Kind and Usual Punishment (1973), to name a few.

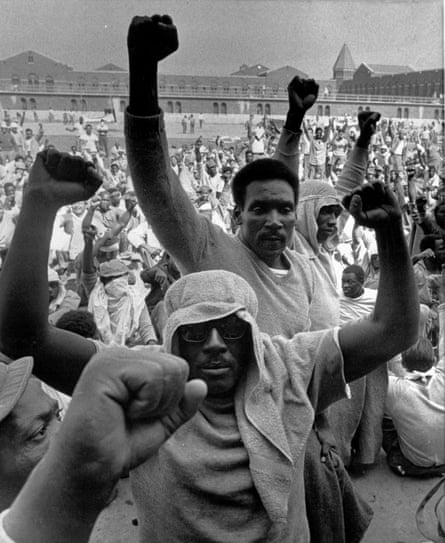

To a wide and receptive public, these opponents of the prison system argued that prisons simply do not work. Prisons attempted to rehabilitate, but high recidivism rates proved they were failing. Prisons were also cruel and unjust, according to these early opponents – not merely as they were currently administered, but as such: caging people was presented as fundamentally harmful and wrong. Mitford, an English aristocrat and journalist, went further, claiming that prisons are “essentially a reflection of the values, and a codification for the self-interest, and a method of control, of the dominant class in any given society”. Increased public attention focused on the prison system, stoked by highly visible prison rebellions in New York City in 1970 and in Attica in 1971, led to a sense that dramatic change was inevitable. It was now just a question of sorting out the practicalities.

Writing in his 1971 book The Discovery of the Asylum, historian David Rothman optimistically asserted: “We have been gradually escaping from institutional responses and one can foresee the period when incarceration will be used still more rarely than it is today.” In his widely circulated 1973 exposé, The New Red Barn: A Critical Look at the Modern American Prison, William G Nash prescribed as the only appropriate policy response a moratorium on all prison construction. This proposal was broadly considered plausible and seemed to reflect an emergent common sense. In April 1972, a moratorium was endorsed by the board of the National Council on Crime and Delinquency, a centrist criminal justice thinktank, as well as by the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice a year later. The latter commission, operating under the Department of Justice, added a call for the closure of all juvenile prisons, and it explicated the emerging consensus about American prisons: “There is overwhelming evidence that these institutions create crime rather than prevent it.”

With such broad public concern, elites wanted to gain firsthand knowledge of the prison system. Lawyers, judges and politicians spent a day or two in prison to get an impression of the conditions. Thoroughly shaken by his experience, Emanuel Margolis, a prominent Connecticut attorney, concluded that prison reform was the wrong answer: prisons had to be abolished. The son of a rabbi, Margolis concluded from his brief prison experience that in incarceration “the total being is involved and affected – his dignity, even his soul”.

Likewise, in 1972, Congressman Stewart McKinney, a Republican from Connecticut, decided to spend 36 hours in a prison to understand what everyone was talking about. As reported by the Associated Press, the congressman “emerged from prison an emotionally strained man”. McKinney concluded that the current prison system is “a big waste of money and human life”. Upon his “release”, he told reporters: “I can’t see consigning any human being to this kind of existence.”

Yet the rate of incarceration today is nearly five times what it was when McKinney emerged from his cell. As political scientist Vesla Weaver has demonstrated, some of the very same politicians who once advocated for segregation switched to advocating for crime policy that would imprison massive numbers of poor people and people of color when it became clear that segregation was a losing cause. Georgia senator Herman Talmadge associated crime, urban uprisings and non-violent civil disobedience, asserting: “Mob violence such as we have witnessed is a direct outgrowth of the philosophy that people can violate any law they deem to be unjust or immoral or with which they don’t agree.” The necessary response: getting tough on crime and building prisons.

In accounting for the rise of what many now call “mass incarceration”, scholars point to race, politics and economics as driving factors. The composite picture has gradually come into focus. The New Jim Crow rightly pushed race and racism center stage, and laid the blame on shapeshifting white supremacy, but more recent work by Michael Javon Fortner and James Forman Jr shows how concern over crime also led black leaders to support the emergent regime of tougher punishments.

Richard Nixon’s war on crime and Ronald Reagan’s war on drugs have long been seen as pernicious forces, but Naomi Murakawa and Elizabeth Hinton have pinpointed the roots of mass incarceration in Johnson’s Great Society, and Marie Gottschalk has spelled out the thoroughly bipartisan consensus thereafter. Perhaps most fundamentally, Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Loïc Wacquant have shown how economic shifts conjured prisons as a catchall solution. In ways that addressed only symptoms and never causes, prisons solved for unemployment on both sides of the bars: both for the urban underclass that was caged, and for rural white communities that built and managed the cages.

But law-and-order politics also signaled a different kind of cultural reorientation: a shift in American religion. Nowhere was this change more obvious and consequential than in elite political rhetoric. During the civil rights era, politicians on both sides of the aisle would trumpet the ideal of justice, often using religious language to do so. Justice was an ideal; it was up to us to make this divine notion a reality. During the era of mass incarceration, Americans’ ambitions for justice have been thoroughly downsized. Justice is now principally a modifier in the “criminal justice system”. Law is principally something to be followed, and its violation (at least by those with little power) is to be punished. Instead of a world where the poor, the weak, and the hungry might be raised up, justice has come to mean little more than the efficient administration of the punitive system we already have. In the moral imagination of mass incarceration, we can imagine greater fairness – for example, in the elimination of racial disparities – but we are generally unable to envision a qualitatively higher justice.

At the same time Doyle was prophesying the end of the prison system, the membership of liberal Protestant denominations, whose leaders and rank-and-file had wielded outsize influence for the duration of the 20th century, steadily declined. Once Protestant theologians Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich graced the cover of Time, Newsweek proclaimed 1976 the “year of the evangelical” and Billy Graham became a de facto presidential chaplain. With the formation of the Moral Majority, conservative, politically activated evangelicals rushed the public square. On the left, meanwhile, public religion receded and secularism triumphed. God’s law was no longer an imperative to strengthen society or democracy; instead, religious rhetoric had become a watchword for virulent conservatism, leaving the potent moral language of religion up to the right. Thus for the right, God’s law served as an admonition to limit the power of the state, and for the left, God’s law ceased to have any significance whatsoever.

The economic, political and cultural forces that conspired to generate mass incarceration were perhaps too fierce for 1970s prison abolition to beat back, and prison abolition retreated into the shadows. But in assessing what went wrong last time around, we can’t help but notice that 1970s prison reformers – even religious prison abolitionists – made their appeals in overwhelmingly secular, pragmatic terms. They pushed for the elimination of racial disparities, the amelioration of prison conditions, and the improvement of measurable outcomes. They did not sufficiently appeal to the deep veins of the American moral imagination: the abolition movement, the civil rights movement, the suffragettes, all of whom were deeply religious in their politics.

Those who’ve been turned on to the problem of mass incarceration by The New Jim Crow and Ava DuVernay’s 13th may not yet realize it, but the organizing metaphors they’ve latched on to do not lend themselves to prison reform; they lend themselves to prison abolition. We will repeat the mistakes of the 1970s unless we emphatically embrace that deeper, broader American moral imagination, one that necessarily taps into our nation’s religious stories, images and rituals.

The problem isn’t merely that we lock too many of our fellow citizens and, increasingly, non-citizens in cages. It’s that locking any human being in a cage is a moral abomination. Those who appeal to slavery and Jim Crow to make sense of mass incarceration are right to identify white supremacy as an abiding American tendency. But another American tradition is that of abolition. As Andrew Delbanco characterized this “recurrent American” impulse in his 2012 book The Abolitionist Imagination, abolitionism “identifies a heinous evil and want to eradicate it – not tomorrow, not next year, but now.” This is the spirit of abolition – and it requires us to think in moral terms, and speak moral language.

When we find our laws enabling barbarism, we must call upon the laws of the gods to abolish them. This cry for divine justice – a justice that rejects state violence, a justice that rolls down like water – is gathering.

We hear it in the testimonies of prison chaplains and educators, and in the exhortations of abolitionists Angela Davis and Mariame Kaba. We hear it in the actions of organizations like Critical Resistance, Black and Pink and The Ordinary People’s Society, whose work prefigures our abolitionist future. And most of all we hear this cry in the brave words and deeds of incarcerated organizers across the nation who demand justice with labor strikes and hunger strikes.

These voices, religious and secular, incarcerated and free, must join together and prophesy justice: a world without prisons, where none is disposable and all are free.

- Joshua Dubler is an assistant professor of religion at the University of Rochester. He is the author of Down in the Chapel: Religious Life in an American Prison Vincent Lloyd is an associate professor of theology and religious studies at Villanova University. He is the author of Religion of the Field Negro and In Defense of Charisma