Editor’s Note: Julian Zelizer, a CNN political analyst, is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University and author of the forthcoming book, “Burning Down the House: Newt Gingrich, the Fall of a Speaker, and the Rise of the New Republican Party.” Follow him on Twitter @julianzelizer. The views expressed in this commentary are his own. View more opinion at CNN. For more on the 1980 election, watch CNN Original Series “Race for the White House” Sundays at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

Will Rogers once quipped, “I am not a member of any organized political party. I am a Democrat.”

That joke has bite in 2020 as Democrats are terrified that they will tear themselves apart before the election ever takes place. The tumult of the Iowa caucuses seemed to symbolize the worst nightmares. Bernie Sanders is the current favorite for the nomination, but several frontrunners have the money and organizational support to take this competition all the way to the convention.

And with the decision still apparently far off, the factions within the party will continue to go after each other with hammer and tong. In the party’s worst-case scenario, President Trump is the last person standing as Democrats are bloodied and beaten up by what they do to themselves.

But those fears don’t have to be realized. Political parties can survive the most intense factionalism. With a skillful leader guiding them, parties can even use internal divisions as a source of electoral strength.

This is what happened in the 1980 election. A former governor of California, Republican Ronald Reagan, brought the conservative movement into the halls of power by defeating incumbent Jimmy Carter. Most historians consider this a turning point that shifted American politics to the right and changed the national debate in ways that continue to influence us today.

Reagan’s Republican Party faced deep fault lines of its own. The conservative movement that had swept through the nation in the 1970s, of which Reagan was a part, consisted of a multiplicity of factions – all of which opposed the persistence of American liberalism.

There was the religious right, which consisted of Evangelical Christians who had decided to mobilize politically to fight abortion, champion “traditional” cultural values, and defend the tax-exempt status for largely white private academies.

The business community also increased its presence in Washington, seeking deregulation of policies that impacted industry as well as tax reductions that would lower the burden on corporations and wealthy Americans.

Meanwhile, neoconservative Democrats and hawkish conservatives wanted to see a buildup of military spending and an end to Richard Nixon’s policy of détente, which had eased relations with the Soviets and China.

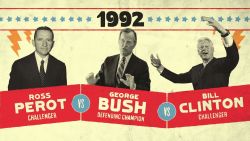

The factions of conservatism were not always in agreement and, in many cases, were at odds over public policy. While the Republicans did not have nearly as many candidates as Democrats do today, Reagan was challenged by two formidable opponents.

There was George H.W. Bush, who had served in a number of major jobs in Washington – including CIA director – and who blasted Reagan’s economic theories as “voodoo economics.”

Then there was Illinois Republican John Anderson, a skilled moderate who had supported civil rights and environmental protection and could boast of deep experience on Capitol Hill. His “campaign of ideas” held great appeal to moderates who feared that Reagan’s extremism would lead him to suffer the same fate as Barry Goldwater in 1964.

Yet what made Reagan so effective as a candidate in 1980 was that he could find ways to unite the factions of conservatism into a temporary, albeit fragile, alliance. Reagan, who was a master communicator from his acting career in Hollywood, honed in on two key themes that cut across the conservative divide: tax cuts and anti-communism. Above all, he consistently prioritized cutting down the progressive income tax system and boosting the defense budget.

Reagan also used Carter as a focal point for his supporters, understanding that Republican outrage about the possibility of two terms would overwhelm any discomfort that different parts of his coalition had with each other. Throughout the fall campaign, Reagan kept returning to Carter in his ads and speeches, blaming the President for the miserable economy and pointing to the administration’s inability to free the American hostages in Iran.

In one of his most potent quips, with the Statue of Liberty behind him, Reagan told followers at a rally that, “Recession is when your neighbor loses his job. Depression is when you lose yours. And recovery is when Jimmy Carter loses his.”

The campaign worked. Reagan defeated Carter in a landslide, winning 489 Electoral College votes to Carter’s 49, and 50.7% of the popular vote. The defeat was stunning for Carter and the Democratic Party. “Despite pre-election polls that had forecast a fairly close election,” Hendrick Smith wrote in The New York Times, “the rout was so pervasive and so quickly apparent that Mr. Carter made the earliest concession statement of a major Presidential candidate since 1904, when Alton B. Parker bowed to Theodore Roosevelt.”

The tensions within the conservative movement never disappeared. They would flare early in Reagan’s first term, as some elements in his coalition, such as the religious right, felt the president was ignoring their concerns. But Reagan would continue to find ways to keep them united enough, going on to win a second term and seeing his Vice President succeed him in 1989.

Factionalism is a difficult challenge for any party. But it need not be a barrier to victory. And in 2020, Democrats can look back to one of their most devastating opponents, Ronald Reagan, to see how the problem can be overcome.