June began with a sunset. One of the most controversial provisions of the notorious post-9/11 Patriot Act expired. Now, a mechanism used for more than a decade to justify the bulk collection Americans’ phone and other “business records” is no longer a part of U.S. law.

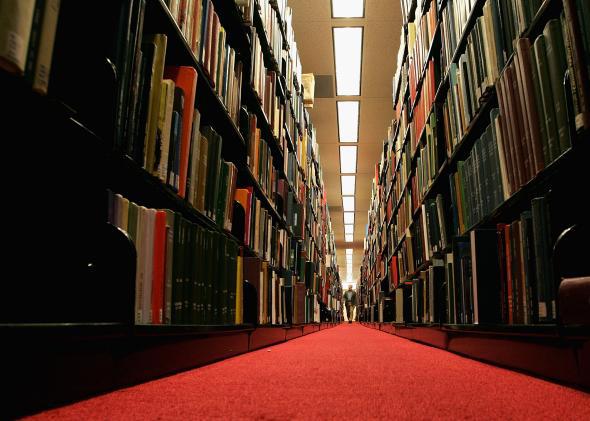

Specifically, the section of the Patriot Act that expired is Section 215, which is commonly nicknamed the “library records provision,” because it called on librarians to hand over patron reading and computer records when requested by law enforcement under a Section 215 request. The law further paired government requests for information with a gag order, so if librarians were asked to hand over patron data, they legally weren’t allowed to alert anyone.

Librarians didn’t take this lightly. For more than a decade, the community has stood in opposition to the Patriot Act, with the Section 215 provision at the top of its list of complaints, claiming that intellectual freedom and the right to research can be preserved only if patron privacy is respected.

Section 215’s sunset does not mean that the NSA doesn’t have an arsenal of other options for secretly retrieving peoples’ personal details without a warrant, nor does it mean that the surveillance powers stripped from the Patriot Act can never again be reinstated. But it does mark an occasion to look back at the wave of anti-surveillance activism against this one notorious law. Before there was Snowden, there were librarians.

Librarians were among the first to raise concerns about the Patriot Act while it was being debated in Congress. The American Library Association was a signatory on the earliest coalition-led opposition to what became the Patriot Act, which passed in October 2001. Within a few months, a University of Illinois survey found that 85 libraries had been contacted with government requests—and that’s likely a low figure, considering that Patriot Act requests came with a gag order.

In 2005 four librarians from Connecticut went to court to challenge a National Security Letter demanding patron data. National Security Letters, whose use was expanded in the Patriot Act, allow the FBI to demand massive amounts of user data from Internet providers without a warrant or judicial review, and they’re always accompanied with a strict gag order. Both the court case and the National Security Letter were eventually dropped, and the Connecticut librarians are among the only recipients of a surveillance gag order who can speak openly about their experiences. That same year, the American Library Association—which has listed intellectual freedom and privacy as core values since 1939—filed a brief in the Supreme Court to challenge the Patriot Act.

But librarians weren’t just fighting in court; they were also making signs to inform patrons that they could no longer guarantee that anyone’s reading habits could be kept confidential. Across the country, librarians were hanging signs that read, “The FBI has not been here. (Look very closely for the removal of this sign.)”

“Everybody should have the right to think about, explore and research ideas that affect their community,” said Jessamyn West, the Vermont librarian who first made the printable signs for other librarians back in 2002.* “There are precious few public places where that kind of intellectual freedom is not just allowed, but encouraged.”

Libraries in Santa Cruz, California, made displays that suggested all questions about the privacy-invasive terms of the Patriot Act “should be directed to Attorney General John Ashcroft, Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. 20530.”

Librarians have also made changes to their procedures and adopted new technologies to circumvent government and corporate spying on users. They began to audit their digital recordkeeping—taking steps to remove different kinds of identifiers that could link patrons with information like circulation records, interlibrary-loan requests, browser histories, and sign-up sheets for public computer terminals. And libraries lobbied vendors to bake in better privacy policies. Now wiping session data and destroying electronic records on library systems has largely become default.

Today, librarians are upping their game. As more and more people depend on the Internet yet still can’t afford a reliable home connection, librarians remain central figures in meeting the information needs of communities.

Now many libraries are hosting regular digital privacy classes for patrons and changing the default search engine on public PCs to DuckDuckGo, a privacy-conscious alternative to Google. Some are switching to Firefox as a default browser on computers in order to install privacy-protective extensions, accompanied with signage alerting patrons that their personal data is less likely to be exploited when using a library computer.

It is difficult to predict the actual extent of the policy change that will result from the Section 215 sunset in the Patriot Act, since the government has a large collection of secretive programs to achieve almost any mass surveillance goal it chooses, and much of Patriot Act remains intact. But it’s good to know that as digital surveillance has become a part of everyday life, our beloved local information professionals will continue to have our back.

Disclosure: April Glaser is an advocate with the Library Freedom Project, where she works to defend to digital rights in libraries.

*Correction, June 4, 2015: This post originally misspelled Jessamyn West’s first name.