On Friday, six judges of the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals—a Trump Supreme Court shortlister joined by five Trump appointees—blessed Florida’s attempt to suppress hundreds of thousands of votes by forcing people convicted of felonies to pay court debt before regaining the franchise. Critics have called Florida’s voter suppression law a poll tax, but that doesn’t fully capture the perverse injustice of the measure. The state has not just forced many residents to pay a tax before voting; it has also refused to tell them how much they must pay. Florida’s law is not a mere burden on the right to vote, but a Jim Crow–style gambit to keep returning citizens locked out of the voting booth forever. By upholding the law, the federal appeals court advanced a frightening legal argument that would let more states revive poll taxes by another name.

Nearly 65 percent of Florida voters approved Amendment 4 in 2018 to restore voting rights to people convicted of felonies. The state constitution now provides that a returning citizen’s voting rights “shall be restored upon completion of all terms of sentence including parole or probation.”

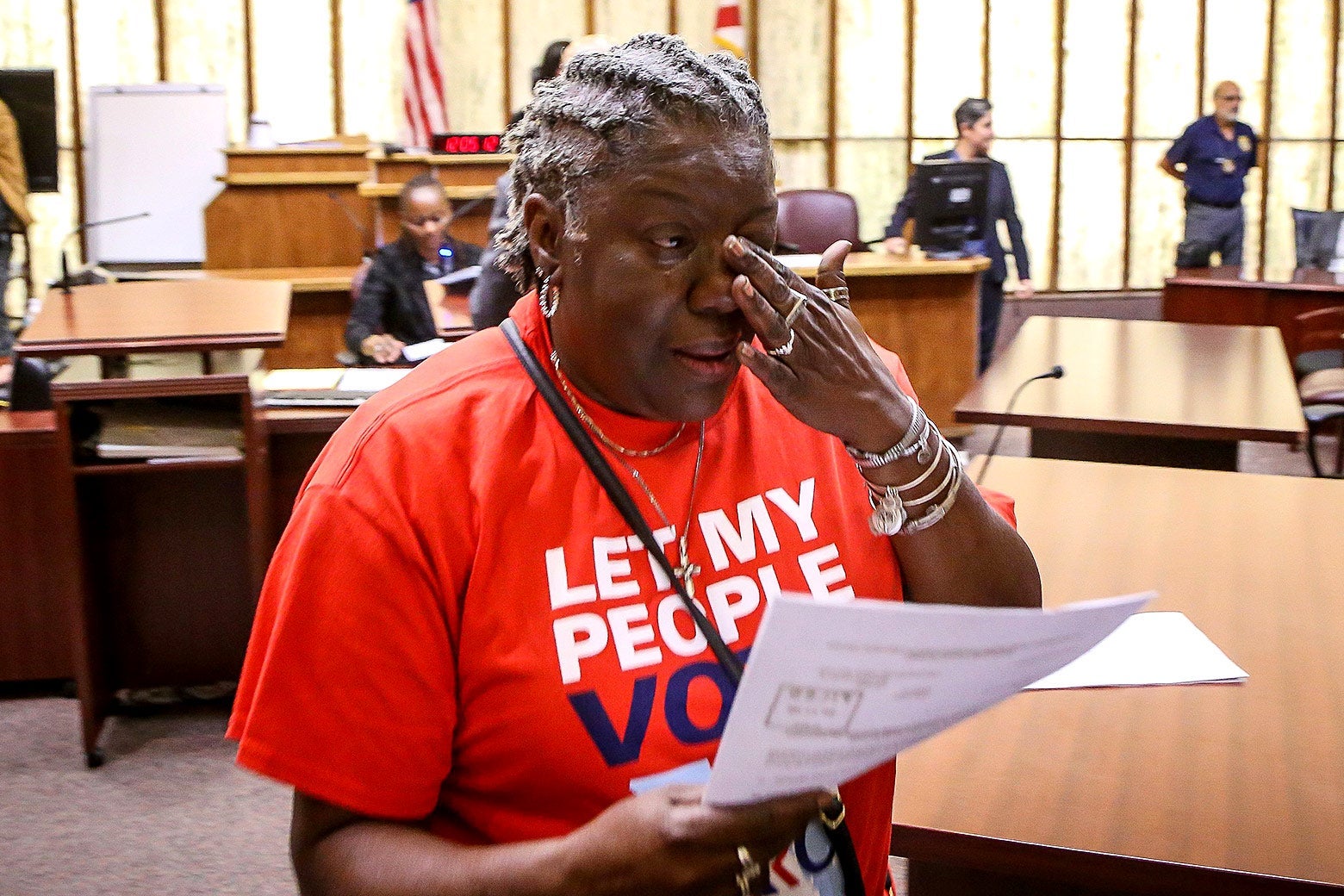

Suddenly, nearly 1.4 million Floridians (including 1 out of every 5 Black adults in the state) were eligible to vote. Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis and GOP lawmakers rushed to abridge that right to restoration, and, in a strict party-line vote, they enacted SB 7066, which required that any returning citizen seeking to have their voting rights restored must first pay all their “legal financial obligations.” These debts include restitution, fines, and hundreds or thousands of dollars in fees that Florida imposes upon people who go through the criminal justice system. The vast majority of fees go unpaid.

SB 7066 makes a clear distinction: Those wealthy enough to pay these debts are deemed sufficiently rehabilitated to vote, and those too poor are not and are thus unworthy of the franchise. This scheme would appear to be blatantly unconstitutional, since the Supreme Court has said that “voting cannot hinge on ability to pay” and the 24th Amendment outlaws poll taxes.

Yet on Friday, Judge William Pryor, one of the judges on President Donald Trump’s list of potential Supreme Court picks, upheld the Florida law in its entirety. Pryor insisted that SB 7066 is not an unconstitutional poll tax because the fees and costs Florida exacts to fund its court system are not a tax but a criminal penalty. This reasoning is highly suspect. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held—most recently in Chief Justice John Roberts’ 2012 opinion upholding the Affordable Care Act—that taxes are largely defined by whether they provide revenue to support government services. Florida’s fees and costs unmistakably do. As Judge Adalberto Jordan noted in dissent, “the fees and costs here do not aim to outlaw any behavior” but rather “serve primarily to raise revenue for the state, and therefore are taxes.” Indeed, the Florida Constitution requires its court system to be self-funding and prohibits the imposition of an income tax—the primary way in which most states raise revenue—making fees and costs a critical source of revenue for the Florida courts. Moreover, fees are applied to every person convicted of a felony regardless of the offense charged or the extent of culpability.

But perhaps the most egregious part of Pryor’s opinion is the way he waves away the extensive findings of fact in the lower court’s decision, which documented the state’s failure to implement any functional system that would effectively restore voting rights to returning citizens. After an eight-day trial, U.S. District Judge Robert Hinkle found that determining how much each person with outstanding fines and fees actually owes was “sometimes easy, sometimes hard, and sometimes impossible.” Hinkle explained that “even with a team of attorneys and unlimited time,” the state was unable to show how much the 17 named plaintiffs were required to pay under the state’s view of the law, let alone the more than 774,000 Floridians who have served their sentences and completed their probation or parole but still owed court debt. (This group is also disproportionately Black.) An expert working with a team of Ph.D.s found that records were generally unavailable by phone or internet; in those records that were available, the information was inconsistent in 98 percent of the randomly selected cases they examined. County officials with substantial experience on criminal and financial records fared no better: They reported that after more than 12 hours of work, they were unable to come up with a definitive calculation of what one returning citizen owed.

Hinkle also found that it was even more difficult, and “often impossible,” to determine the amount paid on a returning citizen’s outstanding court debt. Not only were records of payments inconsistent and missing, but Hinkle found that the state “adopted two inconsistent methods for applying payments to covered obligations”—neither of which had been formally adopted, one of which was concocted in the middle of the litigation, and both of which Florida officials did not understand how to apply. At the time of trial, the Florida Division of Elections said it had 85,000 pending registrations of individuals with felony convictions that must be screened for outstanding fines and fees, but had not completed processing even one.

Pryor’s majority opinion all but ignored just how difficult it is for returning citizens or even state officials to ascertain their eligibility to vote. He glossed over the evidence by stating that “the amount of financial obligations imposed in a sentence is usually clear from the judgment, which can be obtained by the county of conviction.” As the evidence revealed at trial, this claim is misleading at best. Pryor also insinuated that returning citizens should be able to find and reconcile records that have eluded even dogged teams of experienced professionals. But even if they can’t, Pryor says the state has no responsibility “for locating and providing felons with the facts necessary to determine whether they have completed their financial terms of sentence.”

This statement drew a pointed rebuke from Jordan, who registered disbelief at the notion that “a state can impose a condition for the exercise of a right or privilege, and then refuse to explain to a person what the condition consists of or how to satisfy it.” In a separate dissent, Judge Beverly Martin observed that the process for determining just how much returning citizens “must pay to vote” under SB 7066 “has all the certainty of counting jellybeans in a jar,” a reference to the practice of Jim Crow–era election officials who required voters to guess the number of jellybeans in a jar in order to vote. (White voters were miraculously much more adept at this game than were Black voters.)

These fierce dissents did not carry the day. And while the Supreme Court does not have enough time to review this decision before the November election, it might well side with Pryor in the end anyway. Today, the federal judiciary is increasingly dominated by judges who share Pryor’s anti-democratic views. In the 1960s, some federal judges had the courage to halt Southern states’ racist disenfranchisement schemes. According to Pryor, however, such bravery is actually a betrayal of a judge’s obligations. “Our duty is not to reach the outcomes we think will please whomever comes to sit on the court of human history,” he lectured his dissenting colleagues. “We will answer for our work to the Judge who sits outside of human history.”

In a separate concurrence—joined only by Judge Barbara Lagoa, who appears on Trump’s latest SCOTUS shortlist—Pryor expressed the view that judges exhibit real courage by upholding unpopular voter suppression laws. If a majority of judges had shared his views during the civil rights movement, federal courts would have blessed thinly veiled poll taxes and jellybean tests, maintaining Black disenfranchisement indefinitely. Pryor may not care if he is on the right side of “human history.” But he should at least attempt to rule on the right side of the Constitution.