This month, a group of researchers have delivered a sobering look at how affirmative action works for affluent whites at America’s most prestigious university.

From 2009 until 2014, the paper “Legacy and Athlete Preferences at Harvard” finds, 43 percent of the Caucasian applicants accepted at Harvard University were either athletes, legacies, or the children of donors and faculty. Only about a quarter of those students would have been accepted to the school, the study concludes, without those admissions advantages.

The paper is based on data that emerged during the controversial lawsuit that accused the university of discriminating against Asian applicants, which gave the public an unprecedented look behind the scenes of the school’s admissions process. (Closing arguments in that case wrapped in February, but the judge has not rendered a decision.) The study’s lead author, Duke University economist Peter Arcidiacono, served as an expert witness for the case’s plaintiffs, who are seeking to eliminate the consideration of race in university admissions. But the new research was conducted independently without any funding from the plaintiffs, according to a disclosure. And while that suit is attempting to end affirmative action policies aimed at helping blacks and Hispanics, this study focuses on mechanisms that most often give a leg up to Caucasians.

Legacy preferences, which give an edge to the children of alums, have long drawn criticism for skewing college admissions in favor of white, well-off families. But in recent years, athletic recruiting has come under scrutiny for playing a similar role, especially in sports like sailing, skiing, lacrosse, and crew that are particularly popular among wealthier white Americans. The Harvard Crimson’s annual survey found that among the Class of 2019, 43.2 percent of legacies and 20 percent of athletes come from households that earn more than $500,000 a year, versus 15.4 percent of the class overall. Now, rich does not equal white, but as the new paper shows, sports and legacy ties both profoundly shape the white student body at Harvard.

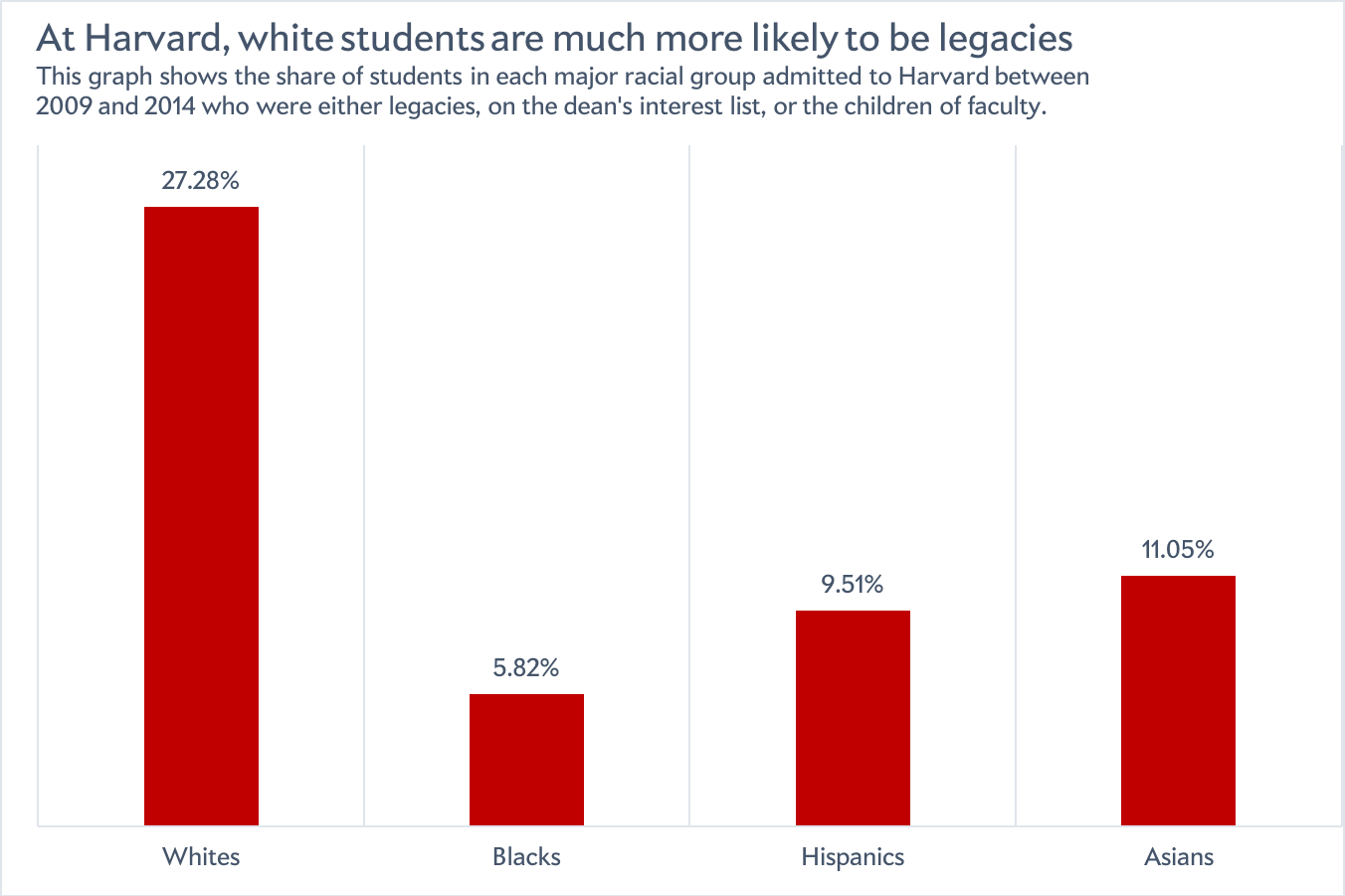

First, white applicants were far more likely to benefit from having family connections to the university, or simply having very wealthy parents, than any other racial group. According to the paper, about 27 percent of white admits were either legacies, the children of faculty or staff (they only make up a tiny slice of the cohort), or members of the “dean’s interest list”—a roster of students whose applications receive extra attention, either because their parents have donated a significant amount of money in the past or might in the future. (Think Jared Kushner.) No other demographic comes close.

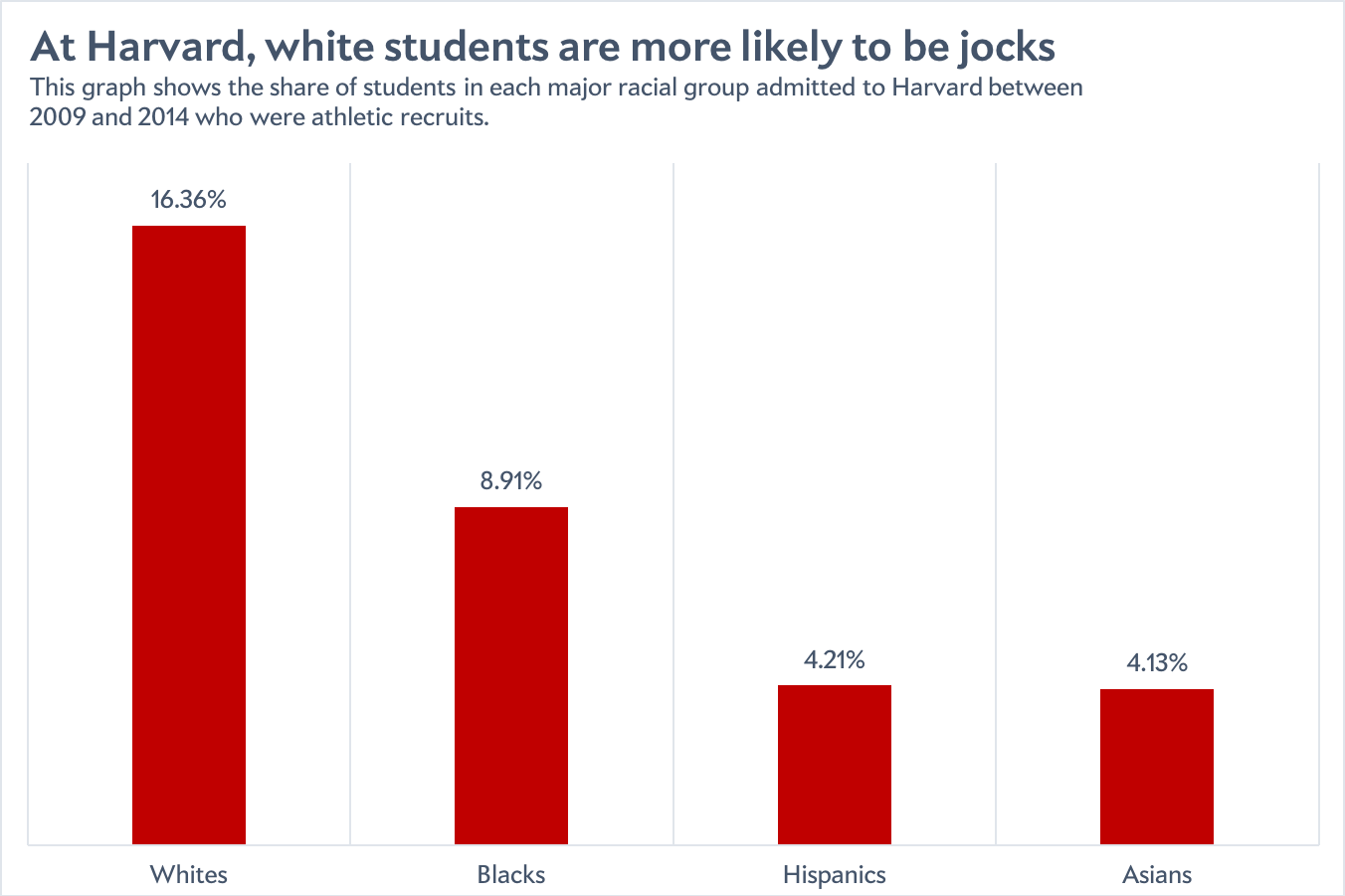

Whites were also far more likely to be recruited for sports: Jocks made up an additional 16 percent of the white students that Harvard admitted, versus roughly 9 percent among blacks and 4 percent among Hispanics and Asians. Overall, approximately 69 percent of athletes accepted to Harvard were Caucasian.

Again, about 43 percent of whites were admitted to Harvard either thanks in part to sports, family connections, or their parents’ donor potential; for other races, the share is less than 16 percent.

(A data note: In real life, some of Harvard’s jocks are probably also legacies. But no, they are not double counted in these graphs. For various reasons, the paper only categorizes students as legacies for analysis purposes if they were not recruited as athletes.)

Unsurprisingly, athletes and legacies had an enormous edge when applying to Harvard—for whites, their admissions rates were 87 percent and 34 percent, respectively, compared to 4.89 percent for normal applicants. Jocks were not particularly academically distinguished as a group. With legacies, dean’s list kids, and faculty children, however, the situation is a bit more nuanced. Their qualifications tended to be stronger than the average Harvard applicant, but weaker than the average student who was actually admitted.

Either way, most of them likely wouldn’t have been accepted without these connections. With a bit of fancy modeling, Arcidiacono and his team conclude that if you took away the admissions advantages, only 26 percent of the white athletes, legacies, dean’s listers, and faculty children Harvard admitted between 2009 and 2014 would still make the cut based on, say, their grades. At most, the white legacy/dean’s list/faculty kid group would have an acceptance rate of about 14 percent.

One final thing to note: Ending legacy admissions wouldn’t make Harvard’s undergraduate class much less white on its own—through their modeling, Arcidiacono and co. estimate that such a move would only knock the share of Caucasians at the university down by a couple of percentage points, since many children of alums would be replaced by more academically qualified white kids. But the change would almost certainly make Harvard more economically diverse.

And anything Harvard and its Ivy League peers can do to make themselves less of a bastion of privilege would be worthwhile. At the moment, the school seems to be running headlong in the opposite direction: In a separate paper looking at a longer time frame, Arcidiacono and co. show that being an athlete or having legacy status has actually become more valuable in Harvard admissions over time, essentially because the share of those students in the student body has stayed steady even as the overall number of applicants to the school has skyrocketed. “Over the course of the 18 years,” the researchers note, “legacies and athletes moved from being four times more likely to be admitted as their non-legacy, non-athlete counterparts to nine times more likely to be admitted.” Perhaps it’s time for Harvard to dial back those advantages a bit. It would be nice if our so-called meritocracy were at least a little bit more meritocratic.