Like many countries around the world faced with rising cases of Coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19), classroom instruction in the Philippines is shifting to remote learning. For 22,668,397 Filipino children [1] there will in all likelihood be no face-to-face classroom instruction for the duration of the 2020-2021 school year [2]. And like all countries committing to fully remote learning, a key question is whether the education system is ready for remote learning for all? The Education Technology (EdTech) Ecosystem profile recently completed by RTI International (RTI) with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID)/All Children Reading-Asia project in the Philippines provides insights that can help answer this question.

The EdTech Ecosystem in the Philippines

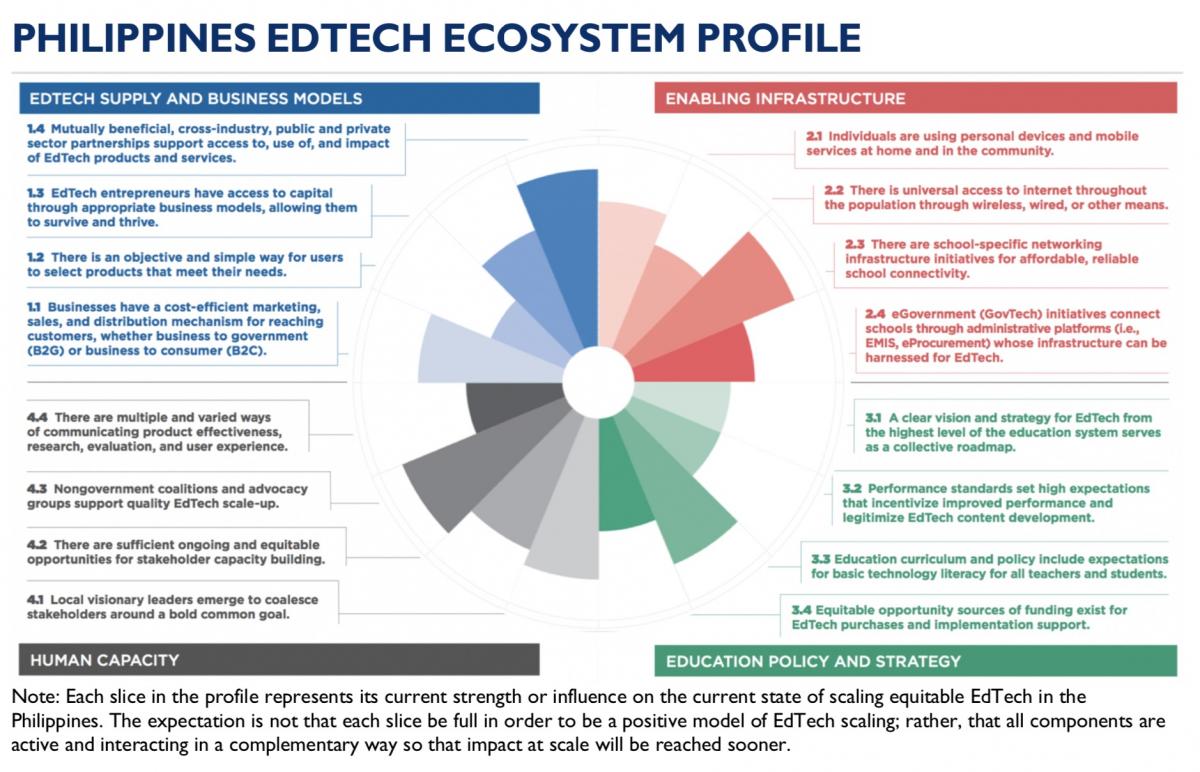

Like all ecosystems, the country is in a constant state of change and all parts of the system are adapting to current circumstances and unexpected events—in this case, the global COVID-19 pandemic. As such, although this model was developed before the pandemic with the intent of describing classroom-based education technology integration, we have found it useful to refer back to the four categories and 16 subcomponents to understand strengths and dependencies that will likely be assets for—or barriers to—a rapid transition to remote learning. This, in turn, can help prioritize investment decisions and ensure that activities are not operating in isolation, but rather leveraging the interrelated nature of the system’s components. The following sections describe the current situation in the Philippines, opportunities and barriers, along the four main categories of enabling infrastructure, EdTech supply and business models, education strategy and policy, and human capacity.

Enabling Infrastructure

The Philippines has, over the past 20 years, invested in school-based IT hardware and networks, not only through the Department of Education (DepEd) Computerization Program, but also a number of smaller initiatives [3]. Unfortunately, the school-specific hardware and devices made available so far are not necessarily the kind of investments that will be needed now for remote learning at home. Moreover, although the Philippines has a very high mobile phone ownership and mobile social media usage, home access to the internet remains low, and connectivity is unaffordable for many. For remote learning in the new school year, children and families will benefit from home-based internet and hardware that will allow them to access online educational resources, participate in virtual classrooms, communicate with teachers and peers, and prepare assignments. Recognizing a gap in family access to the Internet, DepEd plans for a large share of the official instructional content to be delivered through educational television and radio. This broadcast content is being created by teachers, curriculum developers and partners. While accessible and valuable, these instructional delivery models are limited in terms of personalization and learner feedback.

In the absence of a teacher, technology can not only provide access to diverse educational resources but can also provide important scaffolding like audio, video, automatic feedback, and personalization that help children learn basic skills like reading and math. The “school-in-a-bag” activities being supported by Smart Communications and other partners, which have provided laptops for teachers and tablets loaded with educational content for students, are leveraging this potential. These packages were designed with the intent of being used in rural classrooms, or in informal alternative learning centers, prior to COVID-19 school closures. Although still relatively small in scale, they have provided an opportunity for communities to discover tech-enabled learning, have triggered creation of new tablet-based learning apps for literacy, and have provided a means to use existing apps available on the Google Play store or the DepEd commons (see summary table, page 18 of the Ecosystem Profile Report). News reports from the Philippines indicate that local government units (LGUs) are raising money to provide hundreds of thousands of laptops and tablets to students, and to pay for connectivity.

Having the right infrastructure is essential to delivery of content and instruction using technology but this investment is also shaped by other elements of the ecosystem

Having the right infrastructure is essential to delivery of content and instruction using technology but this investment is also shaped by other elements of the ecosystem: government policy, public-private partnerships, demand for specific infrastructure generated by the existing supply of content, and the capacity that individuals have to use any particular technology. Families, local governments, school districts, and other donors need to know if they should invest in internet-connected tablets or a television, if they are fortunate enough to have that choice at all. Efforts to create equity through multi-channel educational delivery are important, but every effort needs to be made to communicate expectations and provide flexible opportunities for all children to have the most appropriate instructional technology for their developmental stage, grade, and subject matter needs. This may look very different from one district to another. Access the ecosystem background brief on EdTech infrastructure for more details.

EdTech Supply and Business Models

Public-Private-NGO Partnerships emerged as one of the strongest components of the ecosystem in the Philippines, because of initiatives like “School-in-a-bag” or fundraising efforts through LGUs, local businesses and even school alumni. These partnerships will be critical to scaling equitable EdTech now more than ever. As hardware and connectivity become more widespread, there will be more incentive for education entrepreneurs to develop digital resources for commercial or open access. The school closures due to COVID-19 are already accelerating this process set in motion by DepEd’s Digital Rise initiative launched in June 2019. This program articulates a goal of modernizing schools, improving ICT literacy, promoting teacher collaboration and ensuring equal access through offline-accessible resource repositories. The need for an easily accessible online repository of open educational resources has been addressed by DepEd, by launching DepEd Commons as soon as schools closed in March 2020—earlier than expected. Searchable by grade and subject area, this online repository is being updated prior to the start of the school year with e-textbooks, supplementary readers, games, and other interactive learning resources. The site has been “white listed”—made available free of data charges through a partnership between the government and telecommunications providers.

While a tremendous effort, such central repositories also harbor challenges to be mitigated, e.g.:

- structuring the resources to make it easy for users to find the right resources at the right level

- guaranteeing a consistent level of quality among the resources; and, especially in the current context

- ensuring it withstands simultaneous access by users that may reach the millions.

DepEd is also creating a separate learning management system where teachers can host their classes, monitor participation and assignments and more. Both of these systems require strong network infrastructure, and capacity on the part of users to access and navigate them. Partnerships and strong leadership at local levels will be necessary to ensure that this isn’t a ‘one size fits all’ approach to remote learning delivery, but a feasible way to provide a menu of equally relevant and effective remote learning options for all. Access the ecosystem background brief on Open Educational Resources for more details.

Education Policy and Strategy

Digital Rise, the DepEd Commons, and the DepEd Computerization Program have all been powerful drivers in preparing Philippine learners for technology-supported remote learning during school closures. Interestingly, unlike many other countries, there is no official, central ICT in Education policy and strategy document under which these efforts fall. Instead, expectations for ICT literacy are built into the curriculum and provide the mandate for hardware and connectivity investments. In the Philippines, 90% of districts and about 80% of schools [4] also have their own ICT policies. Coupled with flexible, decentralized methods of raising funds, schools have freedom to invest and innovate while still being guided by curricular standards. However, the ecosystem study also noted that most “EdTech” in schools is limited to use of standard office productivity (Microsoft) software and basic computer literacy rather than promoting transformative use of technology for enriching the teaching of curricular content.

Scaling transformative EdTech use during school closures requires a strong government vision that encourages the use of technology for multimedia-enriched and personalized learning of curricular content. The current Undersecretary of Education and Chief of Staff has already begun to share the message that the BE-LCP is not just about emergency response but is actually an investment in the future of education through use of technology, innovations in remote learning, and creating smarter learning spaces. [1]

Reiterating this vision and backing it with resources for infrastructure, materials, and training will support all other components of the ecosystem to grow stronger. Now that school reopening in the Philippines has been delayed for another 6 weeks, slated for October 5th, 2020, children will have missed a full 6 months of formal schooling. Opportunities for informal access to learning resources that technology provides (in addition to books and other activities) may mean the difference between maintaining grade level proficiency in basic skills, or slipping back a grade level or more, as some initial projections suggest is possible. Access the ecosystem background brief on EdTech Policy and Strategy for more details.

decentralized efforts, made possible by central leadership—but not tight gatekeeping or controls—was a powerful combination for spreading innovation.

Human Capacity

While central-level vision and strategy is important, EdTech adoption and scale has really taken off where there have been strong and visionary local champions. These leaders, particularly school principals or regional directors, are able to influence EdTech through resource mobilization, introducing innovations in hardware and software, articulating a vision for technology use in the classroom, and ensuring that teachers receive training. The National Educators Academy of the Philippines is moving training programs online, including programs that help teachers and school heads prepare for remote learning delivery.

In the “Human Capacity” component of the ecosystem model it is easy to see how the different parts of the ecosystem are interrelated; for example, capacity building (including teacher training) is not just a necessary part of the ecosystem, it is also made possible by other parts. Public private partnerships and technology hardware or software providers may bundle training with distribution of their product; civil society partners provide opportunities for training; government vision and a system of incentives for upskilling provide a reason for teachers to participate in training; strong infrastructure makes it possible for training to take place online or using blended modalities, and to build networked communities of practice for ongoing professional development.

At present, in preparation for the new school year, DepEd central, NGO partners, and various coalitions and organizations have been active in providing web-based trainings using Facebook Live or Google Hangouts. DepEd development partners, including USAID and RTI, are developing short video explainers to help teachers get rapidly up-to-speed with new policies, tools, and learning resources. Capacity building will take on new forms in this context where rapid response, adaptation and remote working is the ‘new normal’. This comes with the need to trust in teachers’ and school heads’ capacity to design and deliver the best learning continuity plan for their catchment area. The ecosystem study found that decentralized efforts, made possible by central leadership—but not tight gatekeeping or controls—was a powerful combination for spreading innovation. Access the ecosystem background brief on Teacher Professional Development for more details.

Harnessing the potential for technology enabled learning continuity

In consideration of the EdTech Ecosystem profile findings, ACR Philippines supports DepEd’s efforts to provide education continuity during COVID-19 and school closures, in the following ways:

- publishing additional data from the ICT in Education survey completed as part the ecosystem study, including reaching out to districts to know how and if school-based technology use has prepared them in any way to meet the needs of remote learning during school closures.

- launching a longitudinal study of family and learner experiences with remote learning and learning progression during the 2020-2021 school year

- supporting DepEd to evaluate how well the DepEd Commons is meeting the needs of remote learners, and how it could be improved.

- supporting development of additional eResources for the DepEd Commons to cover K-3 reading and math learning.

- developing and delivering additional video explainers and remote learning opportunities for teachers to help them be successful with the BE-LCP.

More about the Ecosystem Profile

The ecosystem model emphasizes that there is not a single definition of "EdTech Readiness" or benchmark that needs to be exceeded in order to be successful. Instead, an ecosystem model describes the interactions and dependencies inherent in a system that result in a given outcome; it encourages us to move away from simple, isolated products or solutions and towards actions that enable the system's full potential. The slices of the model that are larger indicate components that are particularly influential in their contribution to the state of EdTech in the Philippines at the time the study was carried out.

The Philippines Ecosystem profile was developed by RTI International under the USAID-funded All Children Reading-Philippines activity. It is based on the Scaling Equitable Education Technology (EdTech) Ecosystem Model published by Omidyar Network, now known as Imaginable Futures. The original framework was developed by reviewing how China, Chile, Indonesia and the United States have achieved some measure of equitable scale in EdTech use and impact over the past several decades. Four main themes emerged as influential across these four very different contexts, with 16 more specific sub-components. The information used to develop a profile of the Philippines was gathered by a team of researchers from the Foundation for Information Technology Education and Development, Inc. (FIT-ED), and RTI over the course of four months in the second half of 2019. The study team interviewed over 50 key informants from government, civil society, and the private sector, visited schools, consulted relevant documents, and administered a large survey, all designed to answer the questions: what technology is being used in education, how is it being promoted and adopted, what are the effects, and how can good practices be scaled up? The study team also developed four stand-alone technical briefs related to each component of the model.

For more information:

Technical Assistance to Philippines Department of Education (DepEd) is a 2-year US Agency for International Development (USAID) Mission buy-in under All Children Reading–Asia (ACR–Asia). The activities will support USAID/Philippines and DepEd to improve reading outcomes for primary learners, with a focus on increasing impact, scale, and sustainability. The activities will directly contribute to USAID’s education goal to improve early grade reading skills for 100 million children by providing technical and logistical services to USAID/Philippines. Additionally, we will build the capacity and leadership of DepEd to support high impact early grade reading programs through evidence-based, actionable research.

--

Thanks to Saddam Bazer, Ritka Dzula and Carmen Strigel for comments on early drafts of this article

Cover image: Filipino youth testing a tablet-based game. (c) 2019 RTI International/Sarah Pouezevara

[1] According to a presentation made by DepEd to a working group of development partners. “Remote learning” in this case does not necessarily mean technology-enabled learning, although use of technology is recognized as one part of the BE-LCP presenting both challenges and opportunities.

[2] Though a Presidential Spokesperson has mentioned that limited face-to-face classes shall be allowed in “low risk areas” in January 20201 or the third quarter of the school year

[3] For more information, see the technical brief on Last Mile Schools access here. Other available briefs on: Open Educational Resources here; EdTech policy and strategy here and ICT for Teacher Training here.

[4] According to our survey of 405 schools across 205 regions, carried out for the EdTech Ecosystem Study. Data currently in preparation for publication.