Speculation continues to run rampant around the likely contours of forthcoming implementation plans from US Federal funding agencies for public access to research articles (and research data) resulting from the policy guidance issued by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) in the Nelson Memo. Much of that speculation seems uninformed by a nuanced understanding of how policy works, so I thought it would be useful to provide some clarity.

First, to understand where Nelson Memo implementation is going as far as access to research papers, it is essential to understand that this is not a publishing policy. There is no relevant direct relationship between those implementing the policy (federal research funders) and publishers – rather, the relationship is between the funder and the funding recipient (and their institution). This is not to say that it will not affect publishers, it is just not directed at them. Unlike Plan S, this is not a policy intended to regulate (or radically reshape) an industry. That is beyond the goal or remit of the Nelson Memo, even if it will impact some business models. What it does is to regulate the conditions required for a researcher to receive federal research funding, and that is where implementation will focus. It will set requirements on funded researchers, not pick a business model that publishers must follow. On this point, the policies will be agnostic, even if they have impact. The difference is important. Implementation plans will specify an end state, and likely say little (if anything) about the route to that end state. That will be left up to the researcher and their service providers (e.g., publishers) to sort out.

Second, one must look at the policy implementations that are currently in place as a result of the Holdren Memo. Presently, funded authors must ensure that a copy of at least the Accepted Manuscript (AM) version of the paper (or better) is deposited in their funder’s designated repository and made publicly available at or before the time when the allowable embargo period, currently 12 months, expires. Funding agencies, particularly the large agencies covered by the Holdren Memo, are conservative organizations, and given that there is currently no additional funding available to support this new policy and that they already have successful infrastructure in place, Occam’s Razor points to the most likely solution as “more of the same, just sooner”.

The Holdren Memo guidance included a requirement that agencies provide a mechanism for changing the embargo period. Continuing with the existing infrastructure and mechanisms while invoking a shortening of the embargo period to zero offers the most straightforward route for the larger funding agencies, and hence, the most likely implementation strategy.

There is nothing contradictory to the previous policy included in the Nelson Memo – in fact, it goes out of its way to reinforce that it is a “public access” policy, not an “open access” policy, meaning that, while giving agencies latitude, no requirements are placed on licensing and reuse terms for the articles in question. While this may prove disappointing for advocates of the CC BY license often associated with open access (OA), in some ways it better situates the agencies in terms of the Nelson Memo’s emphasis on equity. Again, the Nelson Memo guidance is explicitly agnostic with regard to business models. An insistence on CC BY would most likely eliminate many potential routes to compliance and result in driving things toward the article processing charge (APC) Gold OA model. By leaving out licensing requirements, a broader slate of more equitable routes come into play.

That said, the US Federal policy does not exist in a vacuum. Plan S mandates have already pushed much of the publishing world further toward OA, and the APC Gold route in particular. The implementation outcome suggested here – a copy of the AM in the funder’s repository with no demands on reuse licensing — most likely accelerates that push, but not at the same chaotic speed that an explicitly Gold APC policy would create.

Things have been further complicated in recent days by a letter from the Congressional Committee on Space, Science, and Technology, which raises key questions for new OSTP Director, Arati Prabhakar and her staff to navigate (Dr. Prabhakar was confirmed after the Nelson Memo was issued, but she will oversee implementation in her new role). The data policy questions in that letter are particularly incisive and point to how much that part of the policy needs to be fleshed out. For publications, the letter asks whether further funding is necessary, whether costs will be shifted to research budgets (reducing the amount of research being done), and how equity for authors can be maintained. It is certainly possible that the Administration will request additional funding from Congress for the implementation of the data requirements, otherwise, the costs associated with implementation will be drawn from research budgets. While it is possible that Congress might move to slow or stop these policies, that is not very likely. The budget and appropriations dance will certainly be telling.

For the moment though, let’s assume this most likely of scenarios; a zero embargo requirement for deposit of the AM or better in the agency’s designated repository with no further licensing requirements, takes place. What does that mean for publisher strategy?

Publisher options

Publishers will not in any way be regulated by this policy. Federally funded researchers will have a new set of needs that the market can address. Depending on each journal’s content, culture, and business strategy, there are likely to be a variety of responses.

Gold OA journals

For a Gold OA journal, nothing needs change. Federally funded researchers are already permitted to use their research funding toward paying APCs and it is certainly possible that this policy will drive increases in authors choosing to publish in this manner.

Hybrid journals

Hybrid journals, those that publish on a subscription basis but offer authors optional OA is where things get much more interesting. Some journals are already well along the path to flipping to Gold OA, and the OSTP policy implementations may further speed that transition, particularly for those that publish a high percentage of federally funded research.

But many journals are unsustainable under APC models, and most will see at least some reduction in overall revenues. The optimal strategy for such journals is to preserve and extend subscription revenues as long as possible while continuing to build out robust OA publishing programs. Journals that remain hybrid have two choices:

- Charge an APC for Federal funding compliance – many journals, fearing precipitous declines in subscriptions after the new policy goes into effect, will choose this route, hoping to balance out presumed subscription losses with gains in OA APC revenue. Here the Federally funded author is treated like any other with an OA mandate and required to pay an APC for a fully-OA artricle out of their research funding (or through agreements with their institution), while authors with no such requirements (or with no funding) will continue to have a no-cost route to publishing via subscription-based articles. The article is published OA and the version of record (VoR) is deposited on the author’s behalf in the funder’s repository.

- Allow authors to deposit a Green copy of the AM at no charge – some journals may instead take a “wait and see” approach, allowing authors the ability to deposit the AM of their article in repositories at no cost, at least as long as it has no negative impact on journal subscriptions. If subscriptions fall off a cliff, then the journal changes its policy and requires an APC for Federally funded researcher compliance.

For both these scenarios, subscriptions can be further bolstered by building out content that is not covered by this (or other) policies – review articles, editorials, news stories, and research articles from authors without funding or without access mandates.

To deposit or not to deposit?

There is a middle ground between these two strategies. The current Holdren policies work because most journals deposit articles on behalf of authors. With the 12-month embargo period, the policies are not seen as threatening to subscription revenues and depositing on behalf of authors is seen to offer a competitive advantage over journals that don’t provide that service. In a zero-embargo world, however, the threat is clear and obvious, so it would not surprise me in any way to see this service discontinued. By eliminating automatic deposit for authors, compliance levels are likely to significantly decline, at least over the short term, which may extend the life of the subscription models, if only temporarily. This may force Federal funding agencies to develop new, stricter compliance policies and to invest more in the tracking process. Alternatively, journals could opt to create a new revenue stream from an existing valued service, and institute a charge for depositing an author’s AM in their funder’s repository (presumably less than the cost of a full APC), which could help offset at least some level of short-term subscription losses.

How this will play out will depend on other stakeholders

Which route becomes dominant will depend on how the other stakeholders in the community respond. Researchers, libraries, and universities will all have their say. Key questions:

- How will researchers react to requirements to spend significant portions of their research budgets on publication fees? Previous US policies had no such requirements and were largely no-cost and low effort for funded researchers. Transformative Agreements will continue to shield authors lucky enough to be at an institution that has one in place.

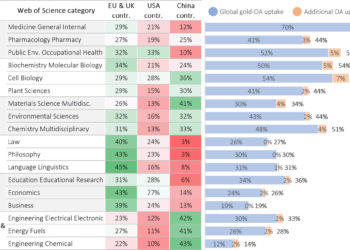

- Will the Nelson Memo drive a wave of Transformative Agreements (TAs) in the US? So far, uptake of TAs by libraries in the US has trailed that seen in the EU. The lack of centralized funding for public institutions (US public universities are state funded, not Federally funded), not to mention the prevalence of private universities, complicates the picture, as funds cannot readily be shifted from “read” institutions to more productive “publish” institutions. This means a concentration of costs on a smaller number of institutions which may not be tenable given current library budgeting levels. Will libraries be okay with effectively shifting the financial burden for APCs from federal agencies to universities?

- For the Green route, the first important question is whether the deposited AM will be considered sufficient for the needs of the community. We know that readers almost always prefer the final, published, typeset, copyedited VoR of papers. In some fields, this preference will be even more extreme. For example, in history journals, much of the revision process takes place after acceptance (as documented here for the William and Mary Quarterly). In fields where citation and quotation is precise, having the community all working from the same version with the same arguments and the same words in the same order on the same pages is helpful.

- And are we any closer to resolving the inherent contradiction in Green OA, that for it to succeed, the subscription model must remain intact? Unpaywall and Unsub, along with COUNTER 5, have eliminated information asymmetries and libraries can very clearly understand what their patrons are reading and how much of it they can access without paying. These services have had the unintended consequence of punishing publishers with the most liberal access policies. Publishers that voluntarily make articles freely available through Green and Bronze OA routes face threats of dropped subscriptions resulting from their support of expanding access to research. Libraries are making pragmatic decisions – if a majority of what’s read on campus is voluntarily made freely available by the publisher, then why continue to pay for it, even if the access model aligns with the library’s ideology? Instead, the publisher is penalized for its goodwill, and the money is shifted over to where it is needed to access materials from publishers who are less supportive of public access, in essence rewarding those with the strictest paywalls. Will libraries support journals that offer compliance at no cost to authors (thus opening up equitable Green OA routes to all authors, not just those with funding) or will this compliance result in funds being shifted to those journals that require payment?

In the end, however, some of these decisions may be taken out of the libraries’ hands. As library budgets continue to decline (or at least struggle to keep up with inflation and growth in the literature), there is less and less money to spend on anything. For example, a report showed that over the last 20 years, the University of California, Berkeley library’s staff has shrunk by 40% and funding per student has decreased by 47%. On top of ongoing cuts, university attendance continues to decline. For many libraries, budgets are dependent on tuitions and student fees, which suggests even greater financial reductions are coming. Moving journal costs out of the library and onto the researcher grants may prove attractive for research administrators struggling to make ends meet.

This suggests that APC-driven Gold OA, with its many inequities, may well end up as the dominant route to compliance, largely by default if no other alternatives are sustainable. In some fields Green OA may not be an option for authors if most publishers decide that they have to flip to Gold OA in order to survive. Although the memo is not a mandate for publishers, publishers’ (and other stakeholders’) responses may affect whether the policy is able to meet the goals outlined by OSTP, and whether in essence it just trades one form of inequity for another.

Discussion

14 Thoughts on "Speculation on the Most Likely OSTP Nelson Memo Implementation Scenario and the Resulting Publisher Strategies"

Thankyou. That is the cogent explanation of federal policy and possible impact of the Nelson memo that I’ve seen, and hope both the federal agencies and publishers read it.

One point. “The current Holdren policies work because most journals deposit articles on behalf of authors. ” I believe that is true just for PubMed Central. I don’t believe the publishers have agreed to deposit any of articles funded by other (non-NIH) Federal agencies to their repositories. There are several agencies that don’t use PMC, and have their own agency repositories.

Will societies be tempted to offer members discounts on OA fees to publish in their journals? They already offer discounts on registration fees for their conferences.

Discounts would need to be carefully considered. A US-based society might not want to create a significant incentive for scientists outside the US to join. That said, some US-based societies already have large overseas memberships.

More generally, OA could shift the marketing focus of societies away from institutions and toward individual researchers. Offering discounts to members is one marketing ploy. Others will likely emerge.

APC (and other fee) discounts for members are already a common practice for many journals. Initially, it was assumed that offering a discount that is larger than the cost of an annual membership would drive membership numbers for societies, but in many cases, this has not proven to be the case. Grants will often cover publishing expenses, but only rarely if ever will cover memberships, so authors often make the choice to pay the higher amount out of their grant funds than to pay for a membership out of their own pockets.

Thanks for this, David! Fantastic piece.

David, thanks for the great forward-thinking perspective here. You say “let’s assume this most likely of scenarios; a zero embargo requirement for deposit of the AM or better in the agency’s designated repository with no further licensing requirements,” however we’ve seen a glimpse of a potential future in which a licensing requirement is indeed mandated within a policy–at least for NIH. Both the NIH Cancer Moonshot and NIH HEAL programs have public access policies that include requirements beyond the current agency-wide policy (see https://www.cancer.gov/research/key-initiatives/moonshot-cancer-initiative/funding/public-access-policy and https://heal.nih.gov/data/public-access-data). Both NIH program policies include:

*Zero embargo (“within four weeks of acceptance by a journal”)

*For AMs (“published research results in any manuscript that is peer-reviewed and accepted by a journal”)

*Deposit to PMC

AND

*Require CC BY or CC0 license

It seems reasonable to consider that NIH may have used these two programs as pilots for a revised NIH-wide Public Access Policy with the same conditions. And it doesn’t seem far-fetched to consider that if NIH moves in that direction, at least some other HHS agencies and other non-HHS agency(ies) could follow suit. Should one or more agencies include a licensing requirement like that in the NIH programs policies, what, if anything would change in your “Publishers Options” ?

David, I question one of the points in your last bullet above. In one portion of that text you’re questioning whether access to services like Unsub, Unpaywall, and COUNTER 5 are having the “unintended consequence of punishing publishers with the most liberal access policies.” Do you have any evidence that is actually happening???

At my institution, and at some others where I’ve had conversations with other librarians, that generally is not happening. We’re not JUST looking at the usage numbers and the cost to access something (although we DO look at that a lot). Cost and cost/use are always considerations, but they’re not the only one. Most of us are going out of our way to NOT punish those that we consider to be the “good players” in the publishing world, for a number of reasons.

Most of those “good players” are smaller to mid-sized shops (by number of journals published), and most have far lower costs/journal than some of the big commercial houses. So cancelling subscriptions from them doesn’t really gain a library much in terms of funds recouped AND it negatively impacts a publisher who is trying to keep costs to their customers as low as possible. So at my institution, and at most of the places I’ve talked to, we are cancelling subscriptions from the places with whom we’re spending the most money, which are almost always the big commercial houses, for (at least) two reasons: 1) some of those publishers with whom many of us are spending millions per year have had a long history of high journal title and package costs, with those costs often just based on historical spend (meaning two institutions could be subscribing to exactly the same set of journals from a given publisher yet one could be paying hundreds of thousands of dollars more or less than the other for that same content), and 2) if we’re going to go through an extremely time-consuming and distasteful serial cancellation process that can sometimes lead to anger (from our faculty and students, when we decide to cancel something they occasionally use), we’re not going to target publishers where we’ll be able to recoup and repurpose a few thousand dollars here and there – we’re going to target publishers where we can recoup and repurpose $400,000 or $500,000. And because most of those large packages have long tails of (relatively) lower use journals, we can reduce our spend with those publishers by lopping off those lowest use journals, saving a few hundred thousand dollars that can be repurposed (at least in part by investing in other scholarly publishing efforts by some of the other “good players” out there), and not TOO negatively impacting our users.

Hi Mel,

A couple of pieces of anecdotal evidence (and your mileage and your library may vary):

Just today, Lisa Hinchliffe noted that she listened to, “One forum where librarians say they absolutely take into account OA availability of content in identifying journals to cancel” (https://twitter.com/lisalibrarian/status/1585677572595224576).

Our own Rick Anderson has regularly made a point of this:

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2013/09/26/when-it-comes-to-green-oa-nice-guys-finish-last/

“Rick said that he had instructed his staff to consider the availability of materials through other venues, including Green OA, when deciding which journals to retain and which to cancel”

The homepage of Unsub is filled with testimonials from librarians who used the data provided to cancel subscriptions.

From my own personal experience in my past work at a publisher with a very liberal access policy (most journals made everything more than 12 months old free to read to everyone), I was regularly called in by our sales team to talk to librarians asking, “if you’re making all this stuff free, why should I keep paying for it.” As you note, if we could get together with the librarian and talk about our efforts to drive access (and imply that if libraries dropped their subscriptions that all the “free” stuff would move back behind the paywall, which nobody wanted), then usually we could stave off that cancellation, at least for that year. The librarians were largely sympathetic to what we were trying to do. But that’s only a subset, those librarians who came to us to have that conversation, rather than those who just dropped the subscriptions and moved on.

Thanks for that info, David. I’d like to think that the places that are looking at that Unsub data (which we are too) are also taking into significant consideration which publishers are working to be good citizens in the scholarly communication system and which are less so. Sometimes the better long term result comes from NOT going after what might seem like a more obvious target in the short term (publishers with a higher percentage of content freely available at or shortly after publication) and instead taking a longer (if potentially more painful in the short term) path to effecting positive change in scholarly publishing.

Agree 100%, and when we had those conversations with librarians, they were uniformly on board. But I suspect there are some out there that don’t have the conversation and don’t make that connection, and some who are forced into super hard choices due to budget cuts, and are making a pragmatic call based on the short term priorities of the researchers on campus.

David, any thoughts how this Nelson decree might affect CHORUS? I’d think that zero embargoes on VoR articles would be quickly unsustainable for journals with high proportions of US government funded works.

David, I think you do a disservice with this: “How will researchers react to requirements to spend significant portions of their research budgets on publication fees?” And given your (and Clark & Esposito’s) proclivity to rely on data, I’m a bit surprised. The calculations I’ve seen indicate that the total cost of publishing US federally funded research articles is about 1.6% of total US federal research funding. I think most would agree that 1.6% is not “a significant portion of research budgets”. Of course, this will vary by author (and particularly by discipline), but overall, publication costs are not going to significantly cut into research funding. Indeed, if federal research funding on average increases about 3% per year (if fluctuates a lot depending on administration and macroeconomic fluctuations, but that’s probably reasonable or conservative as a long-term average) then we only have to give up about half of a year of increase to jump up to funding the same amount of research *plus* publication. Not going to break the bank … or research.

Hi Jeff — I agree that when looked at in the aggregate, it doesn’t seem like a lot. Making your research public is an essential part of doing research, and if one assumes that journals represent a $10B per year market, then even covering the costs of the entire thing only amounts to 5% of the the US $185B annual research funding budget, and the US only publishes a subset of the total papers seen each year so the real numbers are smaller. But it gets more complicated when one looks on the level of the individual researcher. If a lab publishes 10-20 papers per year, then OA costs ranging from $30K to $100K per year means losing a postdoc’s salary, losing a stipend for a graduate student, not buying an essential piece of equipment or a lot of reagents.

To bring some data to the questions as requested, AAAS recently released a study of how researchers pay for OA:

https://www.aaas.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/OpenAccessSurveyReport_Oct2022_FINAL.pdf

Conclusions include that most researchers do not budget for publishing costs and a third of researchers still have not paid an APC; those who have paid APCs are using grant funding to do so. Researchers find it difficult to obtain funds for APCs, and paying APCs means foregoing the purchase of reagents, tools, and equipment or being able to travel to attend meetings.