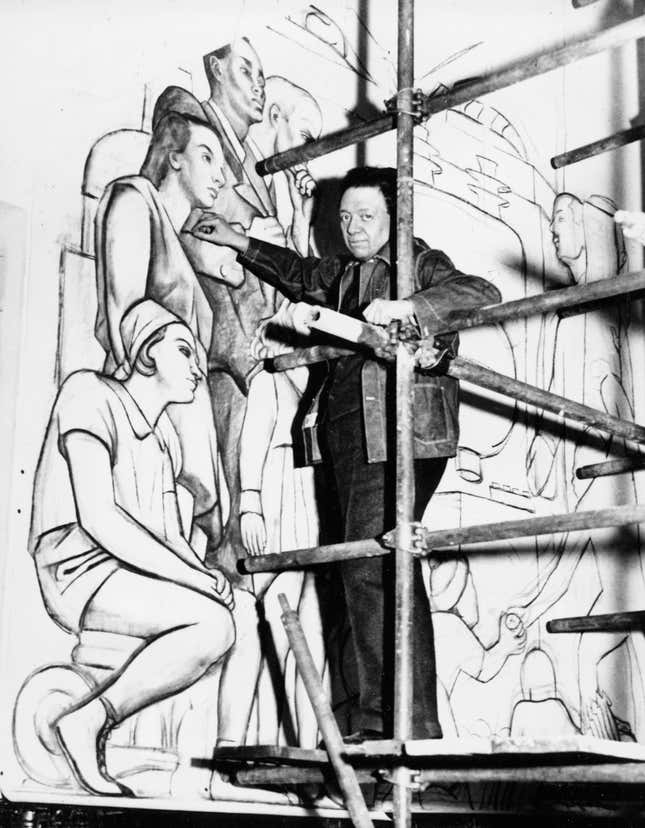

In 1933, an office mural caused an uprising in New York City. Man at the Crossroads, a large fresco by celebrated Mexican painter Diego Rivera, was meant for the lobby of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, but a rogue figure in the composition caused the entire mural to be censored and eventually destroyed.

Nearly 90 years after the event that rattled New York’s artistic circles, the Whitney Museum has brought back Man at the Crossroads in its new show, Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925–1945. For art lovers, seeing the glorious life-size reproduction of Rivera’s vision is a near-religious experience.

“It still gives me goosebumps,” beams Barbara Haskell, the longtime Whitney curator who has been planning Vida Americana for over 10 years.

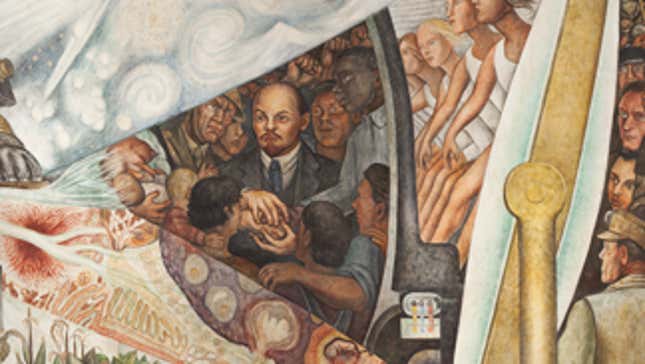

Haskell’s excitement is understandable. Flanking Rivera’s impressive 5 ft x 15 ft, three-panel painting are two original sketches which are being shown publicly in the US for the first time. The sketches show how Rivera, a member of the Communist party, almost imperceptibly yet radically altered his proposal, by slyly adding a portrait of Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin to the right of the central figure.

The addition of the communist icon in the mural was Rivera’s response to criticism that he had sold out to American capitalists. Prior to the Rockefeller commission, which earned him $21,000 (or $412,000 in 2020, adjusted for inflation) Rivera also worked on a series of frescoes for Ford Motor Company in Detroit.

Of course this was a problem for the industrialist Nelson Rockefeller, who commissioned Rivera and other muralists to decorate the lobbies of his midtown Manhattan office complex. The goal, like any lobby art, is to inject a good first impression, to greet tenants and inspire prospective ones to lease space in the building. Rockefeller’s objection was stoked by the conservative New York World-Telegram, which published a story titled “Rivera Perpetuates Scenes of Communist Activity for RCA Walls—and Rockefeller Jr. Foots the Bill,”

Included in Vida Americana is a curious typewritten note dated May 4, 1933, showing Rockefeller trying to reason with the artist:

Dear Mr. Rivera,

While I was in the No. 1 building at Rockefeller Center yesterday viewing the progress of your thrilling mural, I noticed that in most recent portion of the painting you had included a portrait of Lenin. The piece is beautifully painted but it seems to me that his portrait appearing in the mural might very easily seriously offend a great many people. If it were in a private house, it would be one thing, but this mural is in a public building and its situation is therefore quite different. As much as I dislike to do so, I am afraid we must ask you to substitute the face of some unknown man where Lenin’s face now appears.

You know how enthusiastic I am about the work which you have been doing and that to date, we have in no way restricted you in either subject or treatment. I am sure you will understand our feeling in this situation and we will greatly appreciate your making the suggested substitution.

With wishes I remain.

Sincerely,

Nelson A Rockefeller

“The interesting thing about the commission is that both the Rockefellers and Rivera came into the project with misconception,” explains Haskell. The Rockefellers relied on Rivera’s track record of producing murals for other capitalist enterprises with little controversy. Rivera, who was heralded as the “star of the Mexican school” and world-renowned at that point, thought his corporate patrons would cede to his artistic whim.

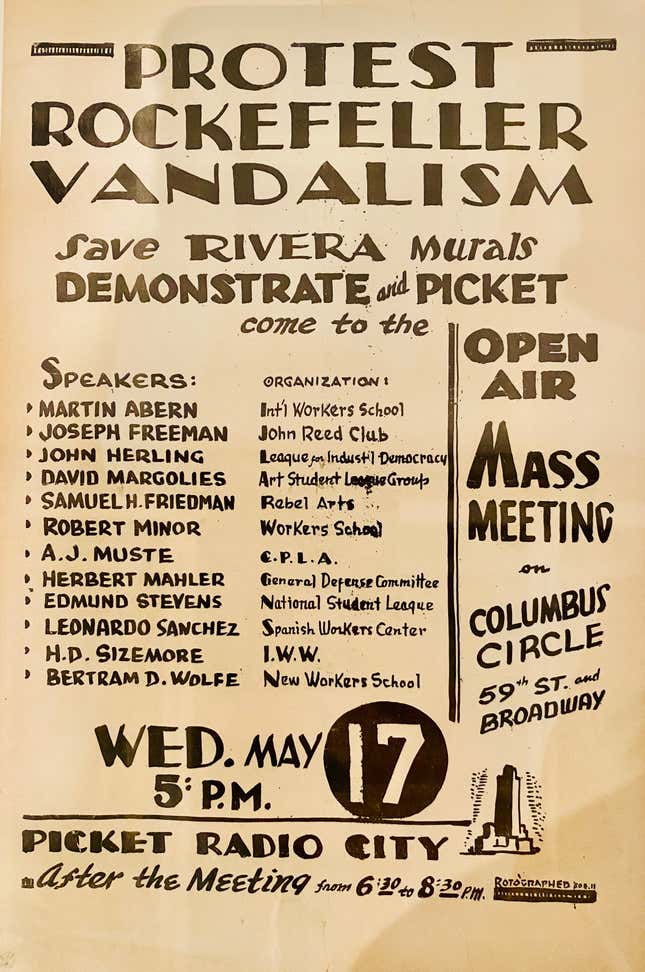

Rockefeller had the entire mural covered when Rivera refused to erase Lenin from the composition. New York artists and advocates, decrying artistic censorship, held strikes in proximity of Rockefeller Center in support of Rivera. But 10 months later, the mural was demolished and replaced with a benign allegorical scene by Spanish artist José Maria Sert.

Despite public embarrassment and canceled commissions, one might argue that Rivera eventually got the final word: In “Man, Controller of the Universe,” a modified version of the Rockefeller Center mural currently at Mexico’s Palacio de Bellas Artes, Rivera inserted a caricature of John D. Rockefeller Jr. cavorting with a woman, with syphilis cells above their heads.