Superhero comics have traditionally not been the place to look for progressive representations of gender or race. Originally written by men for boys, the heroes tended to be straight, male, and white. And not just white, but a certain non-ethnic, Protestant kind of white, despite (or perhaps because of) the ethnicity of their creators, who were often Jewish. At times, the Avengers had four blonde men on its roster and the Justice League frequently had more members who were aliens than were women.

Starting in the 1960s, though, diverse characters could be found if you looked hard enough. Marvel’s Black Panther debuted in the very mainstream Fantastic Four in 1966, and he was eventually followed by the Falcon, Black Lightning, and Power Man (who later went by Luke Cage). Black characters of this era, however tended to be secondary at best, and too often veered toward blaxploitation caricatures, living in the ghetto and speaking a version of jive as envisioned by their mostly white creators.

But one character broke that mold, in all sorts of ways: Storm.

Storm, if you’re unaware, is a mutant member of the X-Men with the power to control the weather. Often that means zapping her foes with lightning, but she also flies on the wind and can generate storms and extreme cold when it suits her. It’s possible your only impression of Storm comes from the X-Men movies, where she was first played as an ineffectual supporting character by Halle Barry, then by a too-young Alexandra Shipp. But in the comics, Storm is much more than that—she’s a groundbreaking character who deserved far better from the movies.

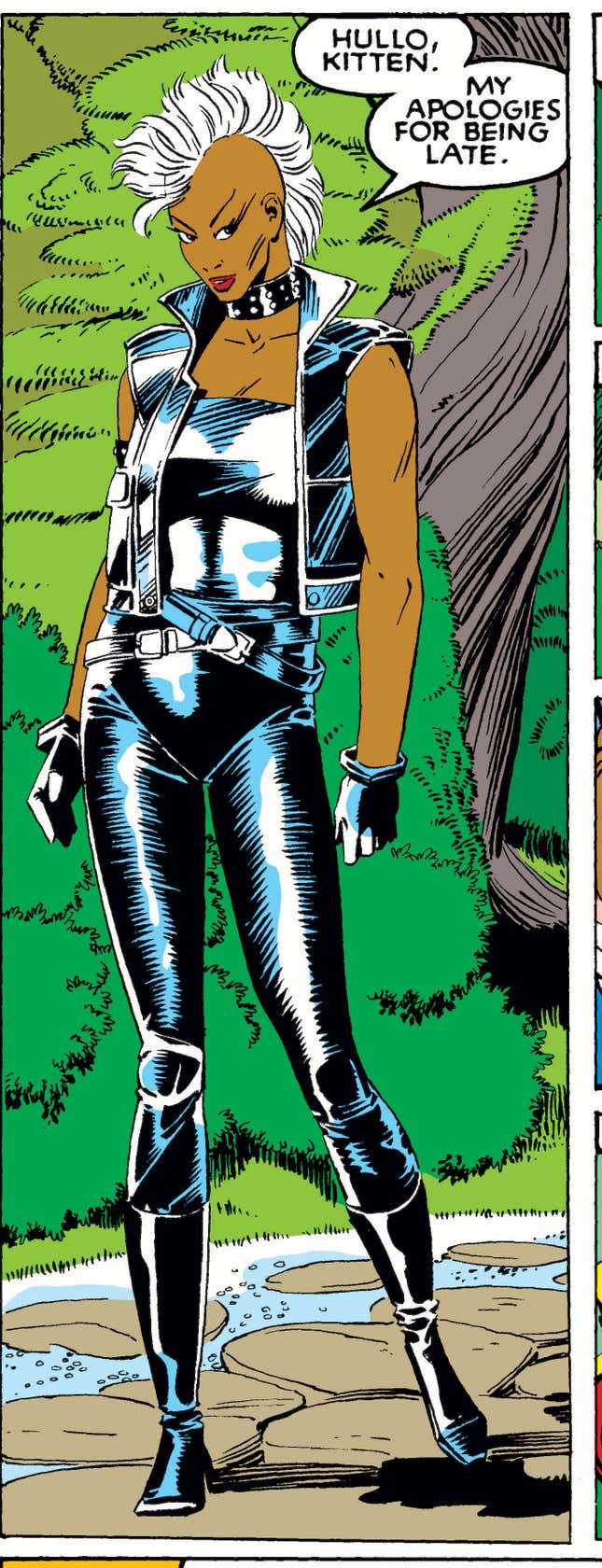

Storm, who first appeared in the mid-1970s, wasn’t just a black, female superhero at a time when there were appallingly few. She became the leader of her team when most women in comics were still sidekicks or helpmates, and later fought off the challenge—without her powers—of a male character who thought the position was rightfully his. Even her appearance became groundbreaking: After years of being costumed like a typical superheroine, with a long cape and flowing hair, she shaved her head into a mohawk, and donned black leather and eye makeup. Her new look was the turning point in her emotional evolution from a demure innocent into a steely leader and comics’ first female badass.

Storm paved the way for generations of tough, assured female heroes in comics and in the movies. The modern incarnations of Black Widow, Wonder Woman, and Captain Marvel are all following her template. Now, nearly 50 years after her debut, it’s time to acknowledge the creation of Storm and her leadership of the X-Men as cultural milestones.

Origin story

Storm was developed by the writer and artist team of Len Wein and Dave Cockrum, both now deceased, and debuted in 1975’s Giant-Sized X-Men No. 1, Marvel’s attempt to revive its flagging X-Men title with a new team of mutants. Unlike the first squadron of X-Men—all of them white, American teenagers who first appeared in 1963—the new version was consciously diverse and international. Among its members were Nightcrawler from Germany, Colossus from the USSR, Sunfire from Japan, Banshee from Ireland, the Native American Thunderbird, and Storm.

As with many comic book superheroes, Storm’s origin story spooled out over the years. Born Ororo Munroe in New York, Storm had a father who was an African-American photographer and a mother who was Kenyan, descended from royalty. She moved to Cairo as an infant with her parents, but when Storm was five, they were killed when a plane crashed into their home as part of an Arab-Israeli conflict. She was buried alive with her dead mother, giving her a lifelong claustrophobia that became a recurring theme over decades of comics.

The orphaned Storm lived as a thief and pickpocket in Cairo before eventually traveling south to Kenya as a teenager where, after discovering her weather powers, she became a local shaman-goddess, watering the crops of local villagers. From there, she was recruited by Professor Charles Xavier to join his new team (the new team was necessary to rescue the old team, which it eventually replaced). Over the decades, Storm left and rejoined the X-Men, lost and regained her powers, and, for a spell, was married to T’Challa, the Black Panther. She remains one of Marvel’s most popular heroes, and by one count, has appeared in more than 7,500 different issues, good for eighth among all comic characters.

While Wein and Cockrum created Storm, she was given life by writer Chris Claremont, who took over the X-Men shortly after her debut. Over 31 years, Claremont churned out another 221 issues, plus dozens of assorted spin-offs, graphic novels, and limited series. In Claremont’s hands, the X-Men became Marvel’s most popular franchise and the basis for 12 movies, in large part because he embraced the human element of these non-human mutants, giving them personality, relationships, heartaches, and growth.

It was through Claremont and his close collaborator at the time, penciler John Byrne, that Storm evolved from a naive innocent to a valued teammate and then, with the departure of Cyclops—the longtime field general of the X-Men—team leader. Her teammates—most notably the short-tempered Wolverine, who threatens to stab Storm when she tells him to sheath his claws or use them on him—were slow to accept her authority:

Her promotion to leader happened off-panel, noted only in passing, as if the writers were unsure it if it would take. Cyclops was a founding member of the team, an archetypal Marvel leading man, and it felt like his absence was temporary. And indeed it was, as he returned on and off over the next several years as he wrestled with a messy personal life.

Changed role, changed image

Storm, too, had her share of superheroic drama over the years, including a possession by Dracula, an attempted suicide to prevent an alien invasion (she was saved when her consciousness was merged with that of a giant space whale), and a duel to the death she wins only after stabbing her adversary through the heart. In Claremont’s writing, those events hardened Storm’s personality, a change that manifested itself visually during a mission in Japan, when Storm radically changed her hair and costume.

According to artist Paul Smith, who drew Uncanny X-Men in 1982 and 1983, he designed her new look as an inside joke riffing on Mr. T, never thinking it would see print. But it was embraced by then-X-Men editor Louise Simonson and Claremont as reflecting Storm’s evolution as a character.

This was the Storm I first encountered, as an 11-year-old lying in my bunk at summer camp. Not yet a comic collector, my idea of superheroes was defined by tepid Saturday morning cartoons like the Super Friends, where personalities were paper thin and all conflicts were resolved in 22 minutes. I had borrowed the “S” issue of The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe, a sort of encyclopedia of all Marvel characters, from a fellow camper and was drawn to Smith’s arresting drawing of a mohawk-ed Storm, sandwiched between Stingray and Stranger. There was something menacing, even disturbing, about this woman in punk attire, regarding the reader warily through her dramatic eye makeup. Assuming she was a villain, I was stunned to read that she wasn’t just a hero, but the leader of the famed X-Men, a team I had only a vague awareness of, without knowing any of their particulars.

This was new. This was exciting. And after that summer, I became a comic book collector, eager to dive into a world that offered characters as richly realized as Storm.

A new era

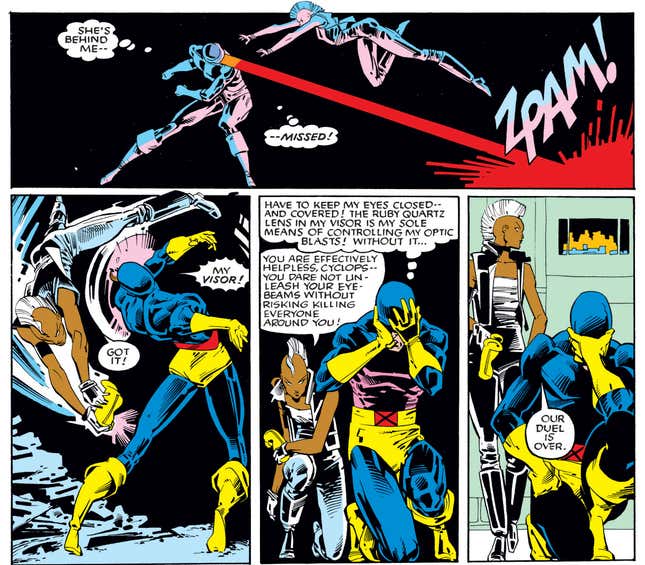

The early 1980s were eventful for Storm, who became an increasingly central part of Claremont’s X-Men narrative. Shot by a weapon that robbed her of her weather powers, she entered into a romance with Forge, the mutant inventor who, unbeknownst to her, designed the device (once she found out, she angrily spurned him). Without her powers, she became both more resilient and more vulnerable, unsure of her place as a normal human in a mutant super team. After a journey home to east Africa where she rediscovered her sense of purpose, Storm returned to the X-Men and challenged Cyclops to a duel to settle who should lead the X-Men. Even without her powers, she wins, cementing her position as leader of the team.

For X-Men readers of my generation, there was nothing strained or forced about Storm’s ascent to leadership. While a noisy minority has protested Marvel’s recent decisions to diversify its line up of white, male characters, I recall hearing no such objections to Storm. Granted, in a pre-internet age, fans had less of a platform to gripe, but unlike some of the more abrupt recent transitions, such as depicting Thor as a woman, Storm’s progression seemed wholly organic. In the hands of Claremont, who spent years laying the groundwork, her rise to leadership seemed almost inevitable.

Comics are designed to be disposable, and the stakes are particularly low. They’re published monthly and mistakes are erased easily, by rebooting or retconning characters, or bringing them back from the dead (a ploy very familiar to any longtime X-Men reader). It would be easy to dismiss Storm’s prominence as pop culture ephemera, not deserving of attention as a civil rights pioneer.

Yet representations matter, even, or particularly, in fiction. Roles played by Dorothy Dandridge, Sidney Poitier, Diahan Carroll, and yes, Bill Cosby all helped reframe American cultural ideas about the lives black Americans could lead and the roles they could play. It’s hard to witness the phenomenon that was the Black Panther movie and not recognize the significance for African Americans, and Africans, of seeing a black superhero, functioning in a universe all his own.

Storm’s leadership of the X-Men coincided with a modest rise in female empowerment across Marvel in the mid-1980s. Janet van Dyne, the once-ditzy Wasp, became chairwoman of the Avengers; Sue Storm—formerly the cringe-worthy Invisible Girl, a character in constant need of rescuing—asserted herself as the Invisible Woman and took control of the Fantastic Four in the absence of her husband, Mr. Fantastic.

Sexism, of course, wasn’t vanquished from comics, and in some ways became more pronounced as the depictions of women became more explicitly sexualized. But after the progress of the 1980s, it no longer felt built into the genre. Any boy or girl reading the X-Men in the mid-1980s knew that a black woman could be a cool, tough leader. And she wouldn’t even need super powers to do it.