I first saw it out of the corner of my eye.

“Deer! Deer!” I whispered through clenched teeth.

Finally. After nearly two hours of waiting, with freezing feet and a numb ass, I was going to do what I set out to do: kill a deer.

In the gloom of the late afternoon December light, a gray form emerged from a thicket near the tree where I perched, 20 feet off the ground. My hunting guide, Fisher Neal, and I sat back-to-back, with the tree trunk between us, on precarious metal platforms Fisher had strapped to the tree months ago.

In front of me lay a clearing, crossed with deer paths. Beyond that, a tangle of trees and bramble disappeared into the New Jersey dusk.

Fisher, who’s also a Yale-trained stage actor and bartender, specializes in taking novices on their first deer hunt. We met that morning in Hoboken—where many a great adventure begins—and drove to a surprisingly rural corner of northwest New Jersey. He spent the morning educating me in the basics of shooting and deer stalking before we headed to his preferred hunting grounds.

For most of the day, the actual killing of a deer seemed a remote prospect. Our discussions that morning about tracking and shooting felt academic and pro forma. Suddenly, with a deer in sight, hunting became very real. I tried to slow my breathing as Fisher instructed, raised my weapon, and unlocked the safety with my thumb. I looked through the scope, with my finger on the trigger, and took aim.

A stereotypical liberal journalist

I’m painfully aware of how much I conform to a stereotype of a Northeastern liberal. I’m a journalist. I drive a Subaru. I recycle assiduously. But I also bristle at being pigeon-holed and having my identity determined by my demographics.

There were other factors behind my desire to start hunting—my eagerness to find a new outdoors challenge; my desire to engage more physically with the world. And if I’m honest, there’s also an element of mid-life crisis, an urge to shake up what about I know about myself and what others think of me. But at least part of the impulse stems from a frustration with America’s polarized political climate, and how uncomfortable I am with the orthodoxies and Shibboleths of our warring tribes.

My politics are my own, and I like to think they’re more nuanced than our two-party system allows. When it comes to guns, I believe in both the need for stricter regulation of firearms, and in the right of Americans to own weapons for hunting and self-defense.

Not long after the Las Vegas shooting last October, I engaged with Second Amendment zealots on Twitter. I tried to convince them of the reasonableness of my positions—that I didn’t believe in banning guns, but that the use of guns should be regulated at least as stringently as cars. I didn’t make much headway. In their eyes, I was just another liberal gun-grabber.

Similarly, in the days that followed February’s Parkland shooting, thoughtful and educated friends shared posts and opinions on Facebook calling for the repeal of the Second Amendment. Again, I waded in and tried to reason with them, arguing that America’s gun problem could be cured without tearing apart the Bill of Rights. They listened politely, but I don’t think I persuaded anyone.

Becoming a hunter, I thought, might give my voice more credibility in these debates. It might also give me more insight into the issues, and perhaps a greater understanding of the mindset of gun owners.

I’m not so naive to think that taking up hunting would necessarily make me more convincing. But it would give me more confidence in my own convictions. It’s easy to argue for strict gun laws when you don’t own one; defending a position that imposes personal hardship is more difficult, and makes the stance that much more credible.

Of course, it’s possible to be a liberal hunter. I even know a few—mostly fellow journalists in western states who every fall disappear into the woods in search for deer or elk. Hunting doesn’t belong to conservatives anymore than hiking belongs to liberals. But demographic shifts over the last half-century have made cities liberal bastions, and left rural areas deep red. Hunting and gun culture have become synonymous with conservative politics, to the extent that the National Rifle Association, an organization once primarily devoted to hunting and shooting safety, has become a de facto wing of the Republican Party.

But perhaps the solution, or the beginning of the solution, to America’s gun problem will come not from further entrenchment into our positions, but more crossing over to the other side. Maybe the solution isn’t just more conservatives willing to consider gun control, but also more liberals learning how to hunt.

Firing .22s and Thompson submachine guns

I have very limited experience with guns, and almost none hunting. I learned to shoot .22 rifles at summer camp in the Adirondacks as a young teenager. I remember lying on my belly in a prone position, pulling back the bolt, and inserting the bullet by shoving it up into the chamber with my pinky. It was loud and exciting, and, looking back, surprising it was allowed at all.

Over the years, I had occasion to shoot a few more times, including at a “Second Amendment Fundraiser” at a shooting range I covered as a reporter in Memphis. I squeezed off a few rounds of a vintage Thompson submachine gun, and somewhere in my attic I still have the evidence, a bullet-hole riddled paper “Thug” target. Again, it was briefly exhilarating, but not an experience I felt I needed to repeat.

After college, when I lived in the Northwest, I was surrounded by hunters and hunting culture. I had opportunities to join friends and coworkers on hunting and fishing trips, but never did. In retrospect, hunting and guns made me uncomfortable. I still had a New Yorker’s visceral aversion to firearms. For my first few months living in Bozeman, Montana, I shared a house with a Yellowstone Park ranger, and once caught a glimpse of his gleaming revolver in his open backpack. There was something both compelling and horrifying seeing the weapon treated so casually—a potent object of destruction tossed in his bag like a spare pair of tube socks.

But for much of the US, gun culture is as much a part of life as church and football. As Fisher and I drove across northern New Jersey, we chatted about hunting, and it quickly became clear he was no dilettante. A Knoxville native, he said he’d grown up hunting with his father and brothers, and he took it very seriously. The crisp, cold weather was perfect for duck hunting, he said, since freezing water would have the birds on the move. He planned on heading out the next day on his own, with no paying clients, to hunt them.

He also hunted turkeys, and as a boy would salvage coyote road kill for the pelts. When he started complaining that New Jersey’s new governor, Phil Murphy, was talking about eliminating bear hunting in the state, I wondered if there was any animal Fisher wouldn’t kill.

Given their over-population, I didn’t have an issue with shooting a deer—at least, not in theory. But hunting bears gave me pause. It seemed a bit too much like African trophy hunting, the killing of lions and rhinoceroses by wealthy Americans for sport. Still, wasn’t I hunting for sport, really? I planned on keeping and cooking the meat of any deer I shot, but that wasn’t why I set out hunting. Given the complication and expense of the undertaking, it was a pathetically inefficient way to fill a freezer, particularly when the C-Town up the street sold ground hamburger for $6 a pound.

I’ve been a meat eater all my life, and have never really given serious consideration to the alternatives. I don’t have the health problems that would suggest eliminating red meat from my diet. As for the ethical considerations involved in meat-eating, I solve them mostly by not thinking about them. I’m aware of the costs of large-scale animal husbandry, both to the environment and to public health, but I reason that humans evolved as omnivores, and there’s nothing inherently unnatural or unhealthy about eating meat. As we drove, I asked Fisher about how he thinks about the relationship between hunting and meat.

“I don’t think it’s a requirement for anyone who eats meat to kill something they have hunted, but I do think anyone who buys a package in a store should understand it was a living thing,” he said.

Hunting, and killing, can evoke powerful, and contradictory feelings, he said.

“There’s the joy of accomplishing something difficult, and that the same time, you’ve killed something,” he said. “Watching it die in front of you is going to make you feel things, like sadness, and you can feel both of those things at the same time.”

There were lots of reasons to hunt, Fisher said. The meat was healthier; it promoted conservation and stewardship of the environment; it prodded us to confront bigger questions about life, death, and our role in the world. But I sensed that Fisher’s primary motivation was the challenge, and the thrill of the chase. He didn’t apologize for his love of hunting.

“Just because you enjoy hunting doesn’t mean you shouldn’t hunt,” he said.

“Insatiable, malevolent, and vain”

Of course, opponents of hunting dismiss this sort of argument as self-important nonsense, a philosophical justification of killing for sport. In a scathing 1990 essay in Esquire (paywall), author Joy Williams reduces hunting to simple blood lust, a desire for man (and it’s almost always men) to impose his will on nature and revel in the pleasure of killing. “Hunters believe that wild animals exist only to satisfy their wish to kill them,” she writes. “And it’s so easy to kill them! The weaponry available is staggering, and the equipment and gear limitless.”

Williams goes on to list the abuses that reduce hunting from sport to slaughter: Hunting with overpowered weapons and bows; using ATVs and snowmobiles; using food as bait; setting decoys; employing biological tricks like doe urine; hiding behind blinds, crouching in tree stands, and working in concert with other hunters to drive game. With so many resources marshaled against it, the prey doesn’t have a chance.

Hunters, Williams argues, are “over equipped… insatiable, malevolent, and vain. They maim and mutilate and despoil. And for the most part, they’re inept. Grossly inept.”

There is, of course, no shortage of writers eager to rebut Williams, authors who valorize hunting and the hunter, placing him in harmony with nature as he’s tested by the elements while connecting to a deeper, more primal self.

In his hunting memoir The Green Hills of Africa, Ernest Hemingway—the patron saint of hunting writers—rhapsodizes about the soul-satisfying freedom he feels tracking kudu in east Africa. In hunting, he realizes who he is and how little he cares about the pressures and expectations of others. Hunting gave him room “to live; to really live. Not just to let my life pass.”

Yet even in that glorious freedom, hunting is inextricably encumbered by the demands of masculinity. For all his claims of independence, Hemingway is caught up in a petty competition with his friend (or frenemy), Karl, who manages to out-hunt Hemingway without even trying. The unacknowledged contest reaches its grotesque nadir when Hemingway discovers the rhinoceros he had so proudly killed was much smaller than Karl’s. He feels emasculated:

I knew I could outshoot him and I could always outwalk him and, steadily, he got trophies that made mine dwarfs in comparison. … Not only beaten, beaten was all right. He had made my rhino look so small that I could never keep him in the same small town where we lived.

Hemingway is at least self-aware enough to explore the toxic masculinity of hunting in his brilliant short work, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” In that story, hunting as a proxy for virility and manhood is taken to its logical, and ugliest, conclusion: Prowess at killing is the ultimate measure of a man’s worth, and women are the spoils.

Obviously, Williams’ trigger-happy menace isn’t the sort of hunter I aspire to be. Riding in the SUV with Fisher, I imagined myself as a sort of tireless stalker Hemingway describes, ranging over vast distances in pursuit of elusive game—the hunter as endurance athlete. But it quickly became clear that I would have to adjust my romanticized expectations about The Hunt. We would be enlisting many of the methods that Williams detests. Tree stand? Check. High-powered rifle? Check. Using food as bait? Check.

Just how sporting hunting should be seems like a matter of vigorous, yet ultimately meaningless, debate. Unless hunters strip down to a loincloth and hunt with a spear, I figured, it’s never going to be a fair fight. Humans have vast advantages available to them, from weapons technology to encyclopedic information about deer habitat and behavior. Any line we draw is going to be arbitrary. Hunting ethicist Jim Posewitz says there’s a three-pronged test to determine if a hunting method is ethical: Is it good for the future of wildlife? Does it violate society’s expectations of hunters (and so jeopardize their right to hunt)? And does it offend the hunter’s own self-respect?

As a novice, I decided to defer to Fisher’s judgment. As I develop as a hunter, I reasoned, I could chart my own ethical path.

In pursuit of hard things

As I thought about why I wanted to hunt, I realized it fit a lifelong pattern of pursuing uncomfortable activities and conditions.

I was a young, awkward glasses-wearing teen, inept in all the typical American team sports when, Mr. Strick, my 10th-grade biology teacher, convinced me to give the cross-country team he coached a try. At last, I discovered a sport in which I could at least hold my own. The pain and suffering of distance running was part of its outsider appeal. Unlike baseball or soccer players, my teammates and I weren’t playing a mere game. We were enduring a trial.

After college in New York, for my first reporting job, I moved to remote northern Idaho. It didn’t matter that this kind of change would be hard; the fact that it was hard was the point. I wanted to prove I could hack it if I gave up my comfortable New York life.

I spent almost a decade in the West, reporting from Idaho, Montana, and Washington State. I climbed mountains, I took up telemark skiing, I traveled from the Yukon to Borneo. But life kept happening. I eventually moved back to New York. I married a woman who, sensibly, didn’t have the same appetite for discomfort. We had children. I had back surgery and developed osteoarthritis in my knees. I can still hike, but my running career is essentially over. There are no more marathons ahead of me.

I see myself now—a man in his mid-40s, softening around the middle, closer to retirement than college. My days of athletic excellence are behind me. My greatest satisfaction comes not from conquering a double black diamond, but watching my daughter sail down an intermediate slope. Maybe that’s enough. Maybe I should relax, enjoy the comforts of middle age, and take satisfaction in the pleasures of home and family.

But I’m not done, damn it.

I still want to test myself. I still want the challenge. I want something harder than the Stair Master in the gym or coaching my kids’ soccer games.

I still want to feel my heart thump on the starting line. I still want to feel the strain and gasping of breath, I still want that satisfaction of looking back at the mountain I just climbed. I want hunting to give me that thrill.

On target

Our first stop that December morning was the rifle range. I was anticipating an indoor facility, with steely-eyed men in tight white t-shirts and plastic earmuffs snapping off rounds like in the movies. Instead, we pulled up to a disheveled-looking outdoor structure maintained by the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife. It consisted of a wooden shelter, with a shelf to rest weapons on while firing, and a range littered with expelled cartridges and shot-up bits of target. Fisher brought his own target stand, a wooden contraption to which he attached a paper bullseye, and a hefty car battery he used to keep it from blowing over in the stiff winter wind.

After reminding me of the basics of gun safety—keep your finger off the trigger, don’t point it at anyone—Fisher started me out with a .22 caliber Ruger rifle, a weapon not too different from the one I shot at summer camp 35 years ago. There was the same excitement of sighting the target, the same loud crack when I squeezed the trigger, the same pleasing thump as the gun shoved itself back into my shoulder.

Satisfied with my progress, Fisher then moved me onto the weapon I would use for hunting, a Savage 212 rifled shotgun. New Jersey prohibits deer hunting with rifles—Fisher explained that it was to minimize the risk of stray bullets traveling where they weren’t welcome in the small, compact state. But shotguns, which have projectiles of buckshot that don’t travel as far, are permitted, and due to a quirk of New Jersey law (or a loophole, depending on your politics), deer hunting is permitted with a rifled shotgun that fires what is essentially a bullet. Called a “slug gun,” it behaves like a rifle from the deer’s perspective, but its chief advantage is the slug won’t travel as far.

Fisher kept the Savage locked in an imposing black case, and handled it carefully. The gun stock was camouflaged, which struck me as fairly ridiculous, but I kept that to myself as he showed me the mechanics of the weapon. The individual rounds were expensive, so he didn’t want me wasting them until I proved my accuracy on the .22.

Once in my hands, the gun was heavy, and cold in the December wind. Fisher loaned me a fingerless glove, and I fiddled about with it and the weapon, trying to get comfortable as I adjusted the scope. Finally ready, I squeezed the trigger slowly, and when it fired, I was stunned by the noise and violence of the action. The kick threw me backward, my eyes shut inadvertently, and I felt I must have jerked the barrel skyward. But Fisher, looking through binoculars, confirmed the shot was on-target, or close enough. I shot a few more rounds, each time less convinced it was going where I intended, though Fisher seemed satisfied. As we left the range, the whole project felt more and more dubious.

The Liberal Gun Club

At some point, if I’m going to be serious about hunting, I’m going to need to buy a rifle. And that seems like a decision fraught with political significance. Every major manufacturer is also a maker of AR-15 assault rifles, the weapons of choice in mass shootings. They’re also financial backers of the NRA, and the beneficiaries of the “gun grabbing” hysteria that propelled gun sales to all-time highs under former US president Barack Obama. Could I buy one without contributing to an industry that causes so much damage?

To find out, I called the Liberal Gun Club.

The Liberal Gun Club was founded in 2007 to provide an alternative voice to the NRA and create a space for “the enjoyment of firearms-related activities free from the destructive elements of political extremism ” according to its website. The club has a lively forum, with discussions ranging from the finer points of Finnish ammunition to frustration with the current state of political discourse about mass shootings.

The club’s membership is booming, spurred by the election of Trump and the frustration many gun owners have with the NRA and its unwavering support of conservative politicians. But it’s also the result of growing unease among minorities who fear violence from the far right, and are seeking to arm themselves in self-defense.

If anyone out there was going to share my combination of enthusiasm for hunting and liberal politics, they were likely to be in the Liberal Gun Club.

When I spoke with Lara Smith, a California attorney and national spokesperson for the club, she quickly disabused me of the idea that there was a left-leaning gun maker out there—a Prius or Patagonia of weaponry. No gun maker could afford to cross the NRA, she says, and they all toed its line to one extent or another. If the club’s members wanted to use their dollars to support right-minded businesses, they focused on local retailers that don’t subscribe to the NRA agenda.

But speaking with Smith also reminded me of how far apart my views on gun control were from even the liberal gun club. It turned out that on most Second Amendment issues, Smith and the club’s members were as inflexible as their hated NRA. Any attempt to restrict the sales of AR-15 rifles, or limit the magazine capacity, was interpreted as a violation of their civil rights. (The LGC has no official policy positions, but it has what it calls opinions.)

Where the LGC differs with the NRA is on background checks—they support expanding them—and on the root causes of gun violence, which they believe stems from poverty, under-investment in mental health treatment, and domestic violence prevention. (The NRA, to the extent it acknowledge gun violence is a problem, argues for increased law enforcement and the institutionalization of the mentally ill.)

On most issues, in other words, the LGC seems classically liberal, except on the one issue it’s organized around.

Protests and politics

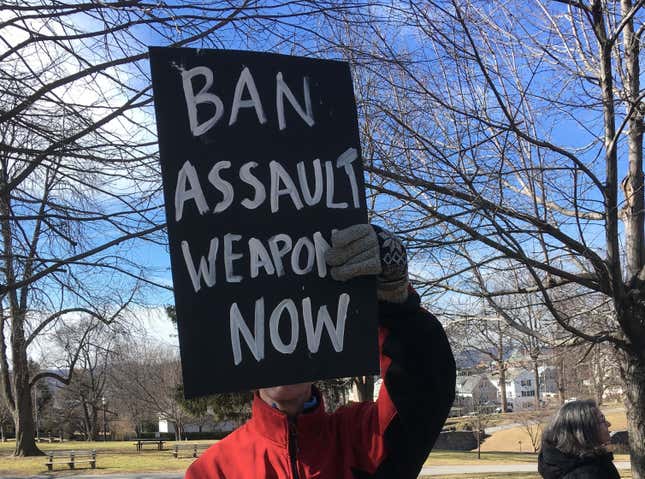

My ambivalence about the hunting project reached its apogee in the wake of the Parkland, Florida, shootings, when anti-gun fervor ran white hot, and the nation seemed more hopelessly divided than ever.

In the days following the shooting, teenagers at my suburban town’s high school organized an anti-gun rally at a park near my house. I wandered over, feeling sheepish about my divided loyalties. About 100 men, women and children were waving signs as cars passed, cheering when they honked in solidarity.

I brought my notebook, and when I saw that George Latimer, the recently elected County Executive for Westchester, New York, made an appearance, I buttonholed him to ask questions about guns. He demurred on some questions, rightly noting that the federal government, not counties, had most of the answers. But I was surprised to find that his views fairly closely aligned with mine. Gun ownership is part of the American experience, and the Second Amendment grants individuals the right to own firearms, he said. “But society has a right to restrict those rights.” Latimer, a Democrat, drew the line at weapons with “no legitimate civilian uses,” but said Americans had a right to firearms for hunting and self-defense.

I pointed out that his views were probably to the right of most of his constituents, certainly the protestors surrounding us. He shrugged. “I’m trying to calibrate a position that is progressive, yet pragmatic,” he said.

After we finished talking, other protestors clustered around me and asked why I was interviewing Latimer. When I explained my project, I braced myself for umbrage. But mostly they seemed curious. Maybe they were just being polite, but the prospect of my buying a gun didn’t seem to faze them.

At home, the opposition was sterner. My wife, who took our children to New York City for the March for Our Lives protest, had signed off on my hunting in principle, viewing it as a provocative reporting project. But when I reminded her one evening I planned to buy a gun, she was less understanding. Did I know how to use one? Did I know how to maintain one? Did I know how to take one apart and reassemble it? Yes, maybe, and no.

What did it matter if I couldn’t disassemble one, I asked her. I can drive a car without knowing how to change the oil. She reminded me her father was a veteran who took guns very seriously. She was concerned I was being too cavalier.

To underscore her point, she dredged up a dark memory from our honeymoon in Greece 12 years ago. In a fit of misguided machismo, I rented a motor scooter without ever having ridden one, and promptly crashed it, damaging the vehicle and casting a pall on the day. I assured her I wasn’t going to be that stupid with a gun, and wouldn’t go hunting without first taking a hunting safety course. We dropped the subject. I felt lucky to escape that easily.

Camouflage and fleece

Before Fisher could actually take me hunting, I had to be properly licensed, which meant a trip to a Walmart in Clinton, New Jersey. There, in the back corner, besides the racks of pink bicycles, was a counter for the express purpose of licensing hunters and selling them gear.

Under Fisher’s guidance, I purchased a non-resident hunting license ($135), a zone permit ($28) and a permit to shoot an antlered deer ($28). New Jersey, eager to develop new hunters, allows for apprentice licenses, which meant I could shoot a deer (under Fisher’s guidance) without first taking a hunter safety course. While I was there, I tossed in a blaze orange vest. Total: more than $200. Hunting is an expensive sport. Spending $6 for a pound of ground beef at C-Town seemed more and more practical.

Now legally equipped, we set off for Fisher’s hunting grounds, deep in a corner of New Jersey near the Pennsylvania border. In a hilly, forested area, we pulled along the side of a quiet road. Before disembarking from his SUV, Fisher pulled out a hunter’s digest with a photograph of a deer, and demonstrated the correct angle for shooting one. I wanted to aim behind the front shoulder for the best chance of a clean kill, he explained. That way, the bullet would puncture the lungs, and they’d quickly fill with blood, quickly drowning the deer. Hitting the shoulder itself would fracture the bone, and spoil the meat around the joint.

As Fisher matter-of-factly explained the anatomy of a deer, the seriousness of the enterprise finally set in. Until now, the day had felt like a journalistic exercise. My role was that of an observer, a reporter tagging alongside an expert—something I had done dozens of times in my career. For the first time that day, I fully appreciated what I was contemplating, and I felt deeply uncertain about it. Was I really prepared to go through with shooting a deer?

Instruction over, we geared up for the sub-freezing afternoon. I bundled up in long underwear, a wool shirt, a fleece sweater, a down jacket, ski socks, thick books, a balaclava, and a fleece hat. It seemed impossible that I could ever be cold. Over all that Fisher gave me camouflage net pants and jacket, which I then covered with my new blaze orange vest. He handed me the Savage 212 to hold and I posed for photos, feeling as bulky as a linebacker and more than a little self-conscious.

Fisher was similarly equipped in orange-and-camo, and once ready, we walked along the side of the road before ducking into the woods. After just a few minutes hiking, we stopped in a clearing: We had arrived at his tree stand. Twenty feet above us, its metal frame was visible in a thick, sturdy oak. Beneath it, corn for bait was strewn about in the low brush. The road was still in view.

Fisher clambered up the tree, and I followed after him, climbing awkwardly and feeling like I was wearing entirely too many clothes for that sort of activity. We each had a tiny platform to stand on, and a narrow seat. I took the one on the side facing the corn, and sat awkwardly with the rifle in my lap and the icy December breeze on my face. It was about 3 p.m. The waiting began.

A long, cold wait

I am not, as my wife and children will attest, a patient man. I frustrate easily. I am perpetually annoyed with slow walkers on New York sidewalks, with automated customer service systems, with standing in line in the supermarket. I am not good at waiting.

Nor do I do well without mental stimulation. I can rarely go more than a few minutes without needing something to read or listen to. I bring a newspaper to the toilet, and make sure I have a New Yorker magazine with me if I know I’m going to eat alone. I dread being caught without something to read, and am astonished by airline passengers who can fly for hours without reading, or watching, anything.

It soon became clear that sitting with nothing to do but watch for deer would be the toughest challenge of my day. After a few minutes of whispered conversation, Fisher and I fell silent.

It was around 3 p.m., and the December sun was already listless. The tops of trees in the distance still caught the light, but the depression where we sat was gloomy. As I waited, my mind wandered. Very occasionally, a car or truck would rumble by. Birds made more frequent appearances, flying in and out of view. The burbling of a nearby stream provided the main soundtrack of the woods.

I fell into a sort of stupor as I looked blankly ahead, straining to see something, anything, emerge from the undergrowth. At one point, white fluff began to float past my head. It was bits of duck down Fisher had tossed into the air, to detect the direction of the wind. Later—minutes? hours?—Fisher again interrupted the tedium by rattling a pair of antlers, hoping it would attract deer.

But neither Fisher’s woodcraft nor my intense peering into the gloaming seemed to work. The woods were still, and the deer were scarce.

In my sights

As the afternoon wore on and the hills grew darker, I gradually realized that the big moment wasn’t going to happen. I was going to end the day without even seeing a deer. Legally, we could hunt for half an hour after sunset, or roughly 5 p.m. The hour was fast approaching. Unless something happened soon, I would leave without a deer, and, I feared, without a story.

But as I swept my vision past the stream for the Nth time, I suddenly saw the distinct shape of a deer, emerging from a thicket. At last!

“Deer, deer,” I whispered hoarsely to Fisher, as I slowly raised the Savage to look into the scope. There it was, the unmistakable back and neck of a deer. I undid the safety and fingered the trigger, waiting for it to emerge so I could get a clear shot. I tried to remember all he had told me, about pulling the trigger slowly, about aiming behind the shoulder.

But something was wrong: The deer wasn’t moving. Maybe it sensed us, and was frozen. I looked again, but it still hadn’t moved. At all. Worse, it was looking less and less deer-like, and more like a tangle of branches that, in that fading light, arranged themselves in a slightly deer-shaped position.

“Is it a buck?” Fisher whispered back at me. He was facing the opposite direction, and couldn’t see. I looked through the scope once more. It was no deer. It was nothing. Shit.

“False alarm,” I finally whispered back. I slumped back in the tree stand, dejected.

After another 15 minutes, our time was up. We stood, stretched, and made our way out of the tree on numb feet. Fisher was apologetic, but philosophical. The woods had been hunted heavily recently, he said, and what deer remained were likely spooked. That was part of the reality of hunting.

We didn’t talk much on the drive back. I was tired and uncomfortably hot in my layers of long underwear, and I sensed Fisher had had enough of my questions. When he dropped me off at the PATH station in Jersey City, he offered me a few cuts of frozen venison he had kept in a cooler; a gift so I wouldn’t go home empty-handed. I thanked him, and I meant it. I boarded the train, bound for New York.

An unfired rifle

Concluding a hunting excursion—one made with the explicit ambition of confronting my own ambivalence about guns—without ever firing my weapon left me with a frustrated, unresolved feeling, like a sneeze interrupted. At this point, I’ve hunted, but I can’t really say I’m a hunter.

In fox hunting—an activity, I will state for the record, in which I have no interest in participating—novice hunters are “blooded” after their first successful kill: Their forehead is literally dabbed with the blood of the newly slain fox.

I wasn’t expecting such an overt initiation. But I still wanted something: a defining experience, a challenge to overcome, a fear to vanquish, a barrier to cross. I wanted the pride of accomplishment, that same deep sense of well-being I get from running a race, or summiting a mountain.

Those pursuits, of course, carry none of the socio-political baggage of hunting, nor the Freudian implications of the rifle that goes unfired.

As I framed my hunting ambitions, the goal was to push myself into a new, unfamiliar territory, one that I found intimidating, even frightening. But hunting isn’t a simple challenge like building my kids a tree house—another recent project I invented for myself that involved mastering new skills and tools. It requires making peace with the act of killing, while confronting the fetishized power of guns in America.

Taking up arms—either for hunting or war—to prove one’s manhood is a tradition as old as our country. We “cannot fully understand American history without understanding masculinity,” writes sociologist Michael Kimmel. Conquest, discovery, exploration, war: It’s all tied up in the desire for proving one’s self.

According to Kimmel, men’s perpetual quest is less about asserting their power, and more about the fear of other men’s judgment. Men are, at heart, deeply insecure, and I’m no different. But in my case, at least, the judgment I fear most is my own. How will I know what I’m capable of, if I’m never tested?

These are not the best of times to declare one’s pursuit of manly ideals. Masculinity, or at least the toxic manifestations of it, has much to answer for: workplace harassment, violence against women, bro culture, homophobia, aggression. The less odious traits associated with masculinity—self-confidence, competitiveness, and independence—are virtues that were once celebrated. But now they seem faded and hokey, like a novel by Rudyard Kipling or the original Boy Scouts manual from 1908; a relic from an older, less enlightened time.

Yet I’m not so evolved that those qualities don’t appeal to me. I want them in myself, and in my children, in my son and daughter. I want to be courageous, adventurous, bold. I want to do hard things and not to shy away from challenges. I want, as Hemingway wrote, “to live; to really live. Not just to let my life pass.”

Will hunting make me a better man? I’m still waiting to find out.