Apples, cherries, and peaches grown in the U.S. are worth more than $4 billion dollars annually. The trees that produce these and other fruits are increasingly at risk as winters warm from climate change.

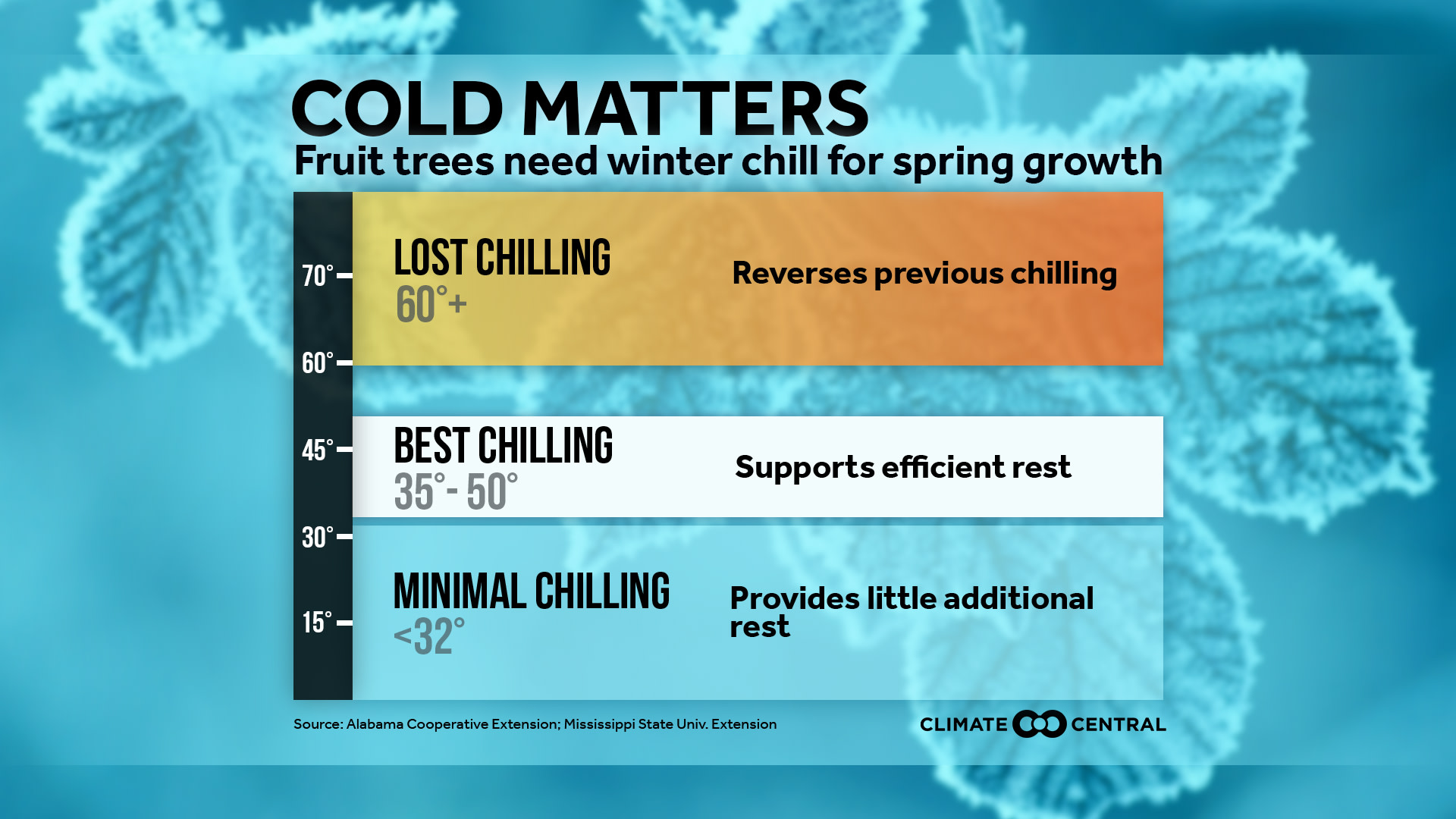

Fruit trees and certain bushes must go through a dormant period each winter in preparation for producing fruit the following spring and summer. This rest period, also known as a chilling period, is directly related to the temperature. For many varieties of trees, the most efficient temperature for chilling is 45°F, with little additional chilling effect at temperatures below 32°F. Brief warm spells in winter have a negative effect — temperatures above 70°F for four or more hours offset any chilling that happened in the previous 24-36 hours.

The amount of hours needed at or below 45°F varies with the type of tree:

Peach: 400 to 1050 hours

Apple: 800 to 1100 hours

Cherry: 1000+ hours

Find chill hour requirements for other fruits here.

Peaches require the least chilling of the three, which is why they are common in milder climates like California, Georgia, and South Carolina. Cherry trees need more chilling, and are more popular in cooler climates like Michigan and Washington State.

Once chilling is complete, the trees prepare to wake up from dormancy and bud after a certain amount of warming takes place. The amount of required warming is cumulative, measured by counting the number of degrees each day above a threshold temperature, usually 40°F. This cumulative warming, combined with how well the tree met its chilling requirement over the winter, determines whether a tree buds early or late in the spring.

Climate change is making winters shorter and milder, resulting in earlier springs. Trees that have flourished in a particular location will likely have decreasing yields in the future, and the favorable locations to grow these fruit trees will shift. That affects regional economies where the crops have been historically grown, in addition to affecting those fruit trees blossoming in your backyard. Also, this seasonal shift alters the locations and return time of migratory species that pollinate the flowers on the trees, potentially reducing yields and causing higher prices at the market.

Consider the very warm February of 2017, when early warming caused apple and peach trees to bloom three weeks early in the Southeast. A mid-March freeze, which is not climatologically unusual in the Southeast, caused severe damage. Combined with losses from blueberries, strawberries, and other crops, the loss was about $1 billion.