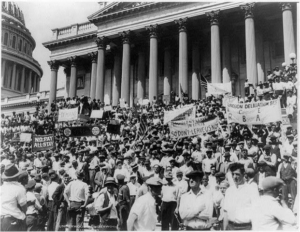

In 1932 WWI veterans laid siege to the U.S. Capitol demanding their service bonuses. Wealthy businessmen plotted to mobilize the disaffected soldiers and overthrow the newly elected FDR. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

That the American press largely ignored an attempt to forcibly overthrow President Franklin Roosevelt only months after his inauguration in 1933 seems less extraordinary in light of the right-wing media’s current efforts to dismiss a far more alarming—and televised—coup attempt on January 6, 2021.

Jonathan M. Katz resurrects that earlier effort in his just-released book Gangsters of Capitalism: Smedley Butler, the Marines, and the Making and Breaking of America’s Empire. Author Sally Denton also did so in 2012 with her book The Plots Against the President: FDR, A Nation in Crisis, And the Rise of the American Right.

A week following the 2021 attack on the Capitol, Denton explicitly linked the two conspiracies. “The nation has never been at a potential brink as it was then—up until, I think, now,” she said. She reiterated her fears in an op-ed in the Post on the first anniversary of the attempted overthrow of the presidential election.

Smedley Butler

Retired Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler asserted that wealthy businessmen were plotting to create a fascist veterans’ organization with Butler as its leader and use it in a coup d’état to overthrow Roosevelt. In a 1935 video clip, Smedley Butler describes the foiled “fascist plot.” (1.22 minutes)

The plot against FDR might well have succeeded had Retired Major General Smedley Butler not blown the whistle on it. The revered former Marine claimed that a representative of some of the nation’s wealthiest men had approached him to lead an army of half a million veterans against the president and install a dictator in his place. It resembled a game plan inspired by European fascists admired by those same men.

A Congressional committee took testimony from Butler, who fingered such titans as J.P. Morgan, Jr., Irénée du Pont and others as the plot’s financial backers, calling them “the royal family of financiers.” FDR echoed Butler when accepting his party’s nomination at Madison Square Garden on June 27, 1936, branding his foes “economic royalists” to wild applause and going so far as to assert, “they are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.” Thanks to Butler, FDR had good cause to know the lengths to which they would go, though few others did.

On the campaign trail in 1932

FDR with daughter Anna and Mrs. Roosevelt. He defeated incumbent President Herbert Hoover in a landslide. Courtesy, Wikipedia Commons.

Roosevelt’s friend Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jr. confirmed that hatred in his tell-all autobiography Farewell to Fifth Avenue, in which he revealed that both of President Hoover’s Treasury Secretaries—Andrew Mellon and Ogden Mills—had privately tipped off leading members of their caste to the probability that the U.S. would go off the gold standard, giving them adequate time to move their assets to Swiss bank accounts while immeasurably worsening the Great Depression just before Roosevelt’s inauguration. Three months later, when the new President began the process by which the U.S. left the gold standard, they apparently moved more decisively against him.

The Business Plot, or “Wall Street Putsch,” today remains largely unknown and is seldom mentioned in Roosevelt biographies, perhaps because the nation’s major newspapers—whose owners largely opposed FDR—mocked it, if they mentioned it at all.

In its report, the Congressional committee charged with the investigation said it “had received evidence that certain people had made an attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country,” but deleted the names of the people Butler had given it. The incensed Butler observed, “Like most committees, it has slaughtered the little and allowed the big to escape. The big shots weren’t even called to testify.” Without those names and further investigation, the report and plot sank into obscurity—until a violent mob stormed the Capitol 88 years later.

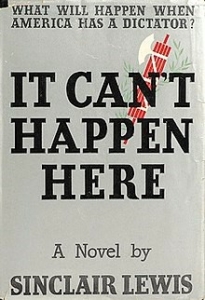

It Can’t Happen Here

Published in 1935, the height of fascism in Europe, Lewis’s book portrays the rise of totalitarian rule in the U.S. with the help of a ruthless paramilitary force. It was adapted into a play in 1936.

Photo Credit: Courtesy, Wikipedia.

A 2007 radio documentary by BBC4 suggests that the plot is so little known because Roosevelt did not charge the conspirators with treason in exchange for a pledge by them not to oppose his New Deal policies. Whether that is true or Roosevelt simply felt that such a spectacular trial would even further divide the country at a time of crisis will probably never be known. That such a conspiracy happened, let alone was all but erased from public memory, seems far more conceivable after the events of January 6—not to mention Republicans’ attempt to block to any such investigation today.

The attack on the U.S. Capitol—not to mention the four years that preceded it—dealt a heavy blow to the American exceptionalism that Sinclair Lewis lampooned in his 1936 play, It Can’t Happen Here. “It” very nearly did in 2021, and may yet still.

Gray Brechin is a geographer and Project Scholar of the Living New Deal. He is the author of Imperial San Francisco: Urban Power, Earthly Ruin.