Abstract

Political insider trading has brought substantial attention to ethical considerations in the academic literature. While the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge (STOCK) Act prohibits members of Congress and their staff from leveraging non-public information to make investment decisions, political insider trading still prevails. We discuss political ethics and social contract theory to re-engage the debate on whether political insider trading is unethical and raises the issues of conflict of interest and social distrust. Empirically, using a novel measure of information risk, we find that senator trades are associated with substantially high levels of information asymmetry. Moreover, based on inside political information, senators earn significant market-adjusted returns (4.9% over 3 months). Thus, our results do not support the prediction made by social contract theory and thereby provide a potential resolution to the ongoing debate on banning stock trading for members of Congress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Concerns about politicians’ insider trading are not new.Footnote 1 Scandals relating to members of Congress using their offices for private financial gains date back to at least 1968 and have plagued both political parties (Barbabella et al., 2009). However, the evidence from the literature on politicians’ investment performance is mixed and provides a range of diverse views on whether or when a politician acts on inside information.Footnote 2

In April of 2012, the United States Congress passed the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act (STOCK Act) which made it clear for the first time that the laws against insider trading also apply to members of Congress and their staff members (Belmont et al., 2020). The STOCK Act prohibits members of Congress and their staff from exploiting non-public information “derived from such person’s position” or “gained from the performance of such person’s official responsibilities” as a means for financial gain (Mesiya, 2021). The STOCK Act also requires members of Congress, the President, Vice President, and all Cabinet members to report any trades exceeding $1000 within 45 days of the transaction. However, there have been many publicized instances where the STOCK Act’s mandates may have been compromised. For example, between early February and early April of 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, twelve senators made 227 stock purchases worth as much as $98 million, and the thirty-seven members of the House made 1358 trades worth as much as $60 million (Fandos, 2020; Mesiya, 2021). Furthermore, not a single member of Congress has been prosecuted under the STOCK Act since its passage almost a decade ago, suggesting certain ineffectiveness and even failures of the STOCK Act (Fandos, 2020; Mesiya, 2021). Nevertheless, it is not our primary goal to assess whether the STOCK Act is an ultimate failure or success.

The main purpose of this paper is two-fold. First, we aim to re-visit the issue of political insider trading by developing a sound ethical framework that integrates political ethics (also known as political morality, the practice of making moral judgments about political action by political agents) and social contract theory. Political ethics not only forbid political leaders to do things that would be inappropriate in private life but also require them to meet higher ethical standards than would be necessary for private life. For example, they may have less of a right to privacy than ordinary citizens and no right to use their office or connections for personal financial benefit. Ultimately, at the core of concern here are issues arising from “conflict of interest.”Footnote 3 Politicians’ insider trading can be a harbinger of conflict of interest as it can create distrust between shareholders and between the firm and its shareholders. In addition, considering politicians’ fiduciary duty to the general public (Blau et al., 2021), politicians’ insider trading may signal the existence of the conflict of interest between themselves, the firms, and other stakeholders. Social contract theory was given its first full exposition by Hobbes (1651) and is associated with modern moral and political theory (Locke, 2003; Rousseau, 1987). Social contract theory views politicians’ ethical or moral obligations as emanating from a societal agreement to form a society where all stakeholders live in harmony. Social contract theory suggests that ethical political insiders should not violate any of the following four moral propositions, i.e., fairness, harmlessness, honoring property rights, and fiduciary relationships. Thus, according to social contract theory, trading by politicians or regulators on non-public information per se should not be considered unethical based on various moral arguments unless such trading raises concerns associated with conflict of interest.

Second, we aim to use the lenses of political ethics and social contract theory to interpret the results of an empirical analysis of financial market dynamics surrounding the electronic stock transactions of U.S. Senators. Specifically, we investigate the performance of stocks purchased by senators and the amount of informed trading occurring around their trades using a novel information asymmetry measure recently developed by Yang et al. (2020). Our results show that senator trades generally beat the S&P 500 over different intervals ranging from 1 week to 3 months following the trade. Additionally, and most importantly, our tests reveal that periods around senator trades are characterized by high levels of information asymmetry, consistent with the notion that senators’ connections with access to knowledge on legislative or lobbying activity may drive such informed transactions. These findings call into question the ethics of insider trading by U.S. senators.

Politicians’ preferences for stocks could be motivated by the engagement in quid pro quo relations with firms (Tahoun, 2014), and therefore their asset holdings may reflect latent corporate connections.Footnote 4 Furthermore, while trading by members of Congress or their staff was not exempt from the federal securities laws (including the insider trading prohibitions) prior to the STOCK Act, there were distinct legal and factual issues that could arise in any investigations or prosecutions of such cases.Footnote 5 The STOCK Act was intended to minimize potential conflicts of interest among politicians, firms, and investors, increase transparency, and combat insider trading by preventing politicians from benefiting based on market-moving information ahead of general investors. However, as discussed in Levinthal (2021), many members of Congress did not fully comply with the STOCK law as recently as 2021, prompting ethics overseers to push for banning lawmakers and politicians from trading individual stocks. Furthermore, the passage of the STOCK Act did not stop the practice of sharing political information with firms impacted by such information but also with financial intermediaries.Footnote 6 Such practice is legal because it allows politicians to solicit feedback from relevant parties on prospective legislation (Kim, 2013b). An unintended consequence (and the subject of recent debate) is the potential transfer of private political information to individuals who can profit from it without having to disclose it publicly. Indeed, there is recent empirical (Gao & Huang, 2016) and anecdotal evidenceFootnote 7 that valuable political information gets transmitted in the market, supporting the notion that a political intelligence industry plays an important informational role.

Although the STOCK Act prohibits non-public information for profit in the first place, political insider trading keeps evolving as financial markets, financial technology, and the associated laws keep changing (Aktas et al., 2008; Blau et al., 2021; Kim, 2013a, 2013b, 2013c; Moore, 1990; Ziolkowski, 2020) indicating the difficulty in finding consensus among business ethicists, financial economists, and policy-makers. In contrast to social contract theory’s dimensions of fairness and level-field information access to all market participants (Klaw & Mayer, 2021; Salbu, 1995), we postulate that political insider trading by the Senate is associated with conflict of interest and can therefore increase social distrust.

Consistent with the view that senators’ purchases are often driven by superior information, our results show that stocks purchased by senators outperform the market over the 3 months following the date of the trade.Footnote 8 Their abnormal return that exceeds the return of the S&P 500 index is about 4.9% over the 3-month period. Moreover, we show that periods around senator trades’ dates are associated with high levels of information asymmetry (AIV). This implies that many more people are trading around these dates, likely on the same congressional knowledge. Interestingly, AIV around senators’ stock transactions is significantly greater than AIV around earnings announcement days. The degree of information asymmetry around senator stock purchase dates is also associated with the senator’s personal characteristics (including age, tenure, and committee membership) and the legislative activity of both the senator and the Congress overall. Many of the same factors also explain the buy-and-hold market-adjusted returns of stocks purchased by senators. The evidence clearly shows that politically informed trading manifests itself in stock prices. In addition, our findings suggest that politicians’ transactions reveal latent and politically informed trades by others who do not have to file. Thus, the results of informed trading we document should be viewed as a lower bound of the extent of political insider trading in the U.S. Senate. In addition, the evidence of elevated levels of information asymmetry around politician trades is consistent with the notion that there is greater potential for conflict of interest. Therefore, our combined evidence does not support the social contract theory.

Our study is distinct from Blau et al. (2021), who examined liquidity and volatility during the post-amendment period of the STOCK Act. It is also different from Belmont et al. (2020). They focused on the potential underperformance of the stock trading by the U.S. senators without dealing with the ethical dimensions of politicians’ trades and the associated information asymmetry aspect. Instead, we regard political insider trading from the perspective of the social contract theory to contemplate the ethical debate related to the conflict of interest and social distrust. Furthermore, our novel empirical approach allows us to capture the extent of information asymmetry surrounding senator stock trades, thereby providing insight into the magnitude of sensitive political information transfer that could lead to the conflict of interest that undermines social trust.

This paper makes several contributions to the literature. First, our findings do not support the prediction made by the social contract theory and suggest that politicians’ insider trading raises the issue of a conflict of interest among market participants that could increase social distrust. This calls for greater scrutiny of politicians’ trades and an expansion of the set of political actors required to file their stock trades. Second, we provide novel evidence of political insider trading and a new method to detect it. Prior literature focuses on analyzing senator portfolios and excess returns (e.g., Eggers & Hainmueller, 2014; Ziobrowski et al., 2004). Third, our paper contributes to the literature on price-based measures of information risk (e.g., Yang et al., 2020) and firms’ exposure to political risk (e.g., Hassan et al., 2019) by showing that politicians’ trades can reveal undocumented levels of information asymmetry. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to introduce abnormal idiosyncratic volatility (AIV) as a measure of the degree of information asymmetry among investors in the analysis of politicians’ trades.

This paper is structured as follows: We briefly review the literature on political ethics, social contract theory, virtue ethics, and political insider trading and develop hypotheses. The following section describes the methodology used and specifies empirical versions of hypotheses. In the subsequent section, we describe the data collection process and report summary statistics. We report our results and associated robustness checks in the following section. Finally, we conclude in the last section.

Related Literature and Hypothesis Development

Political Ethics, Social Contract Theory, and Virtue Ethics

From an ethics perspective, it is widely documented that most forms of insider trading are unethical because it generates profits at other parties’ expense by exploiting information advantages gained through means of position or association (i.e., connections) instead of through public channels (Bhattacharya & Daouk, 2002; Christensen et al., 2017; Gao & Huang, 2016; Jerke, 2010). Indeed, some studies suggest that the buying or selling of securities by insiders with access to non-public information is unethical, unfair, or even illegal (Blau et al., 2021; Brudney, 1979; Klaw & Mayer, 2021; Werhane, 1989, 1991). In contrast, others (e.g., see Manne (1966), Gilson and Kraakman (1984), Meulbroek (1992), Lin and Rozeff (1995), and Bainbridge (2006), among many others) question whether insider trading is economically harmful or advance amoral arguments concerning its impact on the informativeness of prices. Therefore, it is crucial to re-engage in the debate about whether profiting by exploiting political information is unethical. For this task, the political ethics literature allows us to enjoin aspects of ethical expectations derived under social contracting theory with certain aspects of virtue ethics.

Under the STOCK Act, politicians have a disqualifying conflict of interest in a political decision if it is foreseeable that the decision will directly impact their private finances. A conflict of interest arises when the private interests of a politician or official clash with that of the public. The key ethical question is whether private interest could influence, or appear to influence, the voting decisions officials make in their working lives. Henceforth, public officials should not take unfair advantage of their position by using non-public information that could benefit them at the expense of others.

Social contract theory suggests that all stakeholders should live together in society following an agreement/contract that establishes moral and political rules of behavior. For example, if politicians live according to a social contract (Hobbes, 1651; Locke, 2003; Rousseau, 1987), they can live morally by their own choice. Social contracts can be explicit, such as laws, or implicit, such as raising one’s hand in class to ask questions. The U.S. Constitution is often mentioned as an explicit example of part of America’s social contract. It sets out what the government can and cannot do. People who choose to live in America agree to be governed by the moral and political obligations outlined in the Constitution’s social contract. Indeed, whether social contracts are explicit or implicit, they provide a valuable framework for harmony in society. Political ethics requires politicians’ trades to meet higher ethical standards than would be necessary for the personal standard of pursuing financial profit, mainly due to potential conflict of interest concerns (Blau et al., 2021; Jensen & Meckling, 1976; Rawls, 1971; Stark, 2003). Such conflicts of interest can undermine trust (Blau et al., 2021) and make the public lose faith in the integrity of governmental decision-making processes, leading to perceptions of corruption, lack of accountability, and social distrust.

As discussed above, inconsistencies between personal (or private) and political morality in political ethics can be viewed as a “conflict of interest.” However, it is essential to recognize that these two concepts of morality can also maintain a typical positive relationship. Someone who learned the skills necessary in the political sector may apply these qualities in a setting outside of politics, often viewed as a private setting. In contrast, someone entering the political ground may already have the qualities and virtues expected in a professional environment. Reciprocity, as in the context of deriving those traits, is commonly present when entering the field if one did not already learn the qualities. Although both concepts of morality include different expectations, there is a correlation between the two. Whether the virtues and values were acquired or previously held, they factor in and apply to both settings. Those who have emerged into the intense political domain should understand that virtues and morals can influence each other (Mendeluk, 2018). We assert that building one’s character by viewing political morality above private morality can be substantially more ethical when we contemplate the issue of politicians’ insider trading.

Salbu (1995) analyzes the expansive and constricted approaches of insider trading regulation within a framework of basic tenets of the American capitalist social contract regarding the legitimacy of property claims. The insider trading law has progressed from an expansive approach under which corporate outsiders, including politicians, are permitted to trade on non-public information provided such trading does not breach a fiduciary duty. Salbu (1995) further claims that the existing constricted approach to the regulation of insider trading is deficient in meeting the expectations of two core components of the social contract. It discourages procedural equality of opportunity and endorses claims to property not characterized by legitimate methods of acquisition or transfer. Because the old, expansive regulatory interpretation was more consistent with the terms of the social contract concerning property claims, it served our economic and ethical expectations more effectively than the current system. Accordingly, Salbu (1995) suggests that the expansive approach to regulating insider trading be reestablished under United States law.

We apply social contract theory to consider whether it provides a sound ethical foundation for prohibiting trading on material non-public information. Social contract theory shares the premise that whether a practice is “ethical” or “unethical” depends upon whether those governed by such rules have consented or would consent (Dunfee & Donaldson, 1995). We contend that stock trading based on material non-public information by politicians would not be an ideal or even an ethical practice to which most investors would agree because it runs directly counter to the traditional concept of the ethics of fairness (Klaw & Mayer, 2021; Salbu, 1995; Zingales, 2012).

Based on Salbu (1995), Fandos (2020), and Mesiya (2021) further argue that the STOCK Act is an inappropriate and ineffective legal mechanism for remedying issues of political ethics. As a result, concerning political insiders, we consider that an ethical approach might be better than the legal approach to dealing with financial conflicts of interest. In addition, Jerke (2010) advocates for public disclosure of political intelligence-gathering activities by outside actors, such as lobbyists and hedge funds. Jerke (2010) further contends against prohibiting trading on political intelligence by external actors because these actors are merely the Washington equivalents of security analysts, whose information-gathering functions are legitimate, if not desirable. However, unlike Jerke (2010), we maintain that political insider trading is unethical to the extent that it generates profits at other parties’ expense by exploiting information advantages gained through political position or connection (Bhattacharya & Daouk, 2002; Christensen et al., 2017; Gao & Huang, 2016). It is unethical mainly due to conflict of interest even if politicians pass through the hurdle of the legitimacy of property claims.

One competing alternative to the social contract theory related to politicians’ insider trading is the theory of virtue ethics. Virtue ethics emphasize the “right” way to be is that, which stimulates the development of personal characteristics to attain the “good” or “honesty” (Aristotle, 1926; Klaw & Mayer, 2021; Maclntyre, 1984, 1988; Murphy, 1999). For example, Aristotle (1926) proposed nine critical virtues: wisdom, prudence, justice, fortitude, courage, liberality, magnificence, benevolence, and temperance. While Aristotle’s list of virtues does not contain “creating efficiencies” in the financial market, virtue theory can broaden insider trading ethics even if insider trading were legal.

We consider that politicians who trade on material non-public information would need to reconcile their behavior with the virtue of “honesty.” It is crucial to address whether political insider traders are honest. It would be hard to imagine that they are without disclosure to the financial markets and all the market participants. However, political insider traders are unlikely to be honest to all stakeholders because they neither need to take full responsibility for their trading actions nor treat other stakeholders fairly.

While virtue theory is a plausible alternative to social contract theory regarding politicians’ insider trading, we consider social contract theory as more relevant to politicians’ insider trading than virtue theory. That is primarily because virtue theory is mute on price efficiency in financial markets. Thus, the theory of virtue ethics does not precisely predict abnormal financial returns or information asymmetry related to politicians’ insider trading other than the possible existence of the politicians’ dishonesty that could create distrust between shareholders (Blau et al., 2021).

Political realists (Korab-Karpowicz, 2010) criticize that ethics has no place in politics. They claim that moral rules should not bind politicians if they are effective in the political sphere. They further claim that politicians should put more emphasis on the national interest. However, Walzer (1977) points out that if realists are asked to justify their claims, they will almost always appeal to their moral principles. Another criticism comes from those who argue that one should not pay so much attention to politicians and policies but instead look more closely at the larger structures of society where the most severe ethical problems lie (Barry, 2005). However, we maintain that while one should not ignore structural injustice, too much emphasis on structural injustice issues could potentially lead us to neglect both the practice of information exploitation for private benefits and the issues arising from conflict of interest. We further contend that the current practices of politicians’ insider trading are creating social distrust among market participants.

Politicians and Insider Information Trading

Early evidence of potential conflict of interest consistent with political insider trading is provided by Boller and Ward (1995). They show that out of a random sample of 111 members of Congress and Senate, 25% of members’ stock transactions were directly linked with legislative activity. After that, several studies attempted to quantify the performance of politicians’ stock investments and to answer whether they make abnormal profits, but the results were mixed. Ziobrowski et al. (2004) show that between 1993 and 1998, senators’ stock trades outperform the market by approximately 10% per year. Yet, Eggers and Hainmueller (2014) show that between 2004 and 2008, Congress members’ trades underperform the market by, on average, 2–3% annually. Perhaps, pre-STOCK Act data can generate conflicting results depending on the period of the analysis because “it is also possible that members simply stopped reporting their incriminating transactions once they realized that academics and the media were watching them” (Kim, 2013c, p. 170).

Huang and Xuan (2019) show that in the year following the establishment of the STOCK Act, there were no surprise mergers or earnings announcements that politicians took advantage of, and they suggest that the STOCK Act might have stopped politicians’ insider information trading. Yet, given the plethora of anecdotal evidence in 2020 alone and the fact that many senators need to file corrections every year, it is still unclear whether the STOCK Act has effectively increased transparency and reduced insider trading. Blau et al. (2021) empirically examine the sample of stocks held by members of Congress compared to control stocks and find that liquidity significantly worsens, and stock volatility substantially increases during the post-STOCK Act amendment period. They conclude that restrictions on non-corporate insider trading are associated with unfairness and harmfulness.

Hypothesis Formation

Social contract theory provides a sound ethical foundation for prohibiting insider trading in the U.S. (Klaw & Mayer, 2021; Salbu, 1995). As Salbu (1995) notes, insider trading profits generally render the transaction unfair because a trader with inside information does not deserve the gains she receives by utilizing that information. Given the opportunity, market participants would generally refuse to agree to a system that permits insider trading (Tramontano, 2017; Zingales, 2012) because earned merit has little to do with rewarding those who trade with the unearned advantage of inside information. We posit that the same ethical problem applies to politicians, as trading on inside political information may create unearned benefits.Footnote 9

We also maintain that political insider trading by the Senate has the potential to disrupt fair equality of opportunity. We postulate that political insider trading can pose potential conflicts of interest among firms, shareholders, politicians, and financial intermediaries. The breach of the fair equality of opportunity increases social distrust and raises the potential for conflict of interest among stakeholders, thereby adversely affecting financial efficiencies. However, gauging the true extent of political insider information trading is not easy. Kim (2013b) points out that the STOCK Act is not binding for all legislators.Footnote 10 Thus, the trading activity of senators (and potentially House members) should be viewed as a subset or as a proxy for all others who have access to the same information but do not file their transactions (Kim, 2013b). As a result, there is a potential for politicians who have access to material non-public information to disseminate it in violation of some of social contract theory’s four ethical propositions (i.e., fairness, harmlessness, honoring property rights, and fiduciary relationships). Second, to the extent that the four ethical principles are adhered to, it should not be possible for politicians to generate high abnormal profits simply because they access insider information. For example, abnormal returns could be possible when investing in industries that fall under the jurisdictions of their committees (Karadas, 2018) or even without a committee link when investing in local firms (Eggers & Hainmueller, 2014) because in these cases, politicians may be in a better position to exploit public information.

Nevertheless, Kocieniewski and Farrell (2020) document that members of Congress with oversight of industries such as financial services, defense contracting, and health care earned huge gains recently through well-timed trades in the market. Given their advantages in terms of oversights of such industries, local firms, and timing, it is questionable whether the system should allow substantial financial gains to politicians. Moreover, most current literature on government insiders fails to consider differences in financial know-how between corporate and government insiders. The latter, e.g., a legislator, can use her inside information to make an informed trade. Still, a lack of skill might prevent her from making abnormal returns achieved by a financial analyst trading on the same information, as Ferguson and Voth (2008) showed.

Social contract theory assumes that whether a practice is right or wrong depends upon whether those governed by such rules have consented or would consent (Dunfee & Donaldson, 1995). Thus, we would argue that high financial gains by politicians should not be a practice most people would agree with because it runs counter to traditional capitalist concepts of the moral equality of opportunity and associating moral desert with merit (Blau et al., 2021; Salbu, 1995; Zingales, 2012).

Initially, we contemplate whether the Senate’s inside trading could generate a positive financial gain. One can expect politicians’ trading to be free of systematic use of legislative and political information after the STOCK Act’s enactment. Belmont et al. (2020) analyze the buy-and-hold abnormal returns of politicians between March 2012 and 2020, and they confirm the previous results of Eggers and Hainmueller (2014) by showing that the actual returns of politicians outperform the market returns but fail to outperform the industry-size benchmark. Their results support the premise that senators possess valuable legislative information while lacking company-related inside information.Footnote 11

To the extent that the social contract theory is valid, we speculate that politicians’ investments should not generate high abnormal returns.

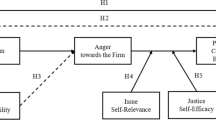

H1

The average stock returns following politicians’ trades do not outperform the market returns.

We also examine whether stock returns following politicians’ trades exceed industry returns (Corollary 1). Any finding of senator stocks outperforming the market but not the industry could imply that (a) information acquired from their legislative activities helps choose the suitable industries to invest in, and (b) senators lack the skills and/or additional company-type information to select the best stocks within industries.

Additionally, the fact that the senators are not outperforming industry portfolios does not necessarily mean that others with access to the same information as these politicians (e.g., their staff members or other (state) legislators) are not doing so. Therefore, one must be careful when claiming that politicians and their aids do not make abnormal returns using their informational advantage. It is also essential to note that only a small number of political insiders report their transactions. Furthermore, it might be worth noting that not outperforming the industry portfolio does not necessarily mean they are not informed. Politicians can consistently beat the market and make abnormal returns by picking the right industry. Therefore, an analysis of abnormal returns cannot easily lead to solid conclusions about whether the politicians’ trades are informed or not. By examining not only abnormal returns but also by introducing a more sophisticated method based on a price-based measure of information risk (i.e., the AIV of Yang et al., 2020), our approach allows us to gauge the extent of trading stemming from legislative and political inside information and reveal its most relevant factors and possible channels.

Following Kim (2013b), we aim to test to what extent the trading activity of senators could serve as a proxy for the trading of all other politicians who possess the same information but are not required to file their transactions. In this case, periods of the senators’ trades should be associated with a high level of information-driven trading or information asymmetry.

Our approach allows us to examine whether politicians (i.e., senators) belong to the “first wave of informed traders.” This is plausible because their work puts them in a position to be the first to receive value-relevant news (Kim, 2013c), i.e., they may be directly informed because they are aware that their legislative activities would cause future stock price changes. Therefore, to the extent that the social contract theory is valid, we expect political insider trading with more information-driven transactions will not happen. We further construct our corollary hypothesis to examine whether politicians are in the first wave of informed traders. Thus, we postulate the following:

H2

Politicians’ stock trades do not occur in periods of higher probability of information-driven trading.

Our subsequent interest is whether informed trading by senators is associated with their tenure, membership on essential committees, and other personal characteristics used in previous research (e.g., Ziobrowski et al., 2004). Moreover, since the spouses and children of senators also have to disclose their trades, we can observe if senators try to mask their insider trades by giving information to their family members or potentially by trading in their name. This expands on Karadas (2018), who shows that politicians’ spouses outperformed the market before the STOCK Act. Additionally, as Eggers and Hainmueller (2014) show, there is a possibility that a senator might receive corporate insider information from firms’ lobbying efforts related to legislation before their committees. Henceforth, we expect that the involvement of lobbyists and the level of activity in Congress can also influence the extent of informed trading. Accordingly, we anticipate the following:

H3

If political insider trading exists, its extent is related to politicians’ characteristics, the account (self or family member) used to trade, and relevant lobbying and legislative activity around the transaction date.

Methodology

Concept of Abnormal Idiosyncratic Volatility (AIV)

Yang et al. (2020) show that their price-based measure of information risk, AIV, relates to insider trading,Footnote 12 institutional trading activities, and short selling. There is a positive relationship between the AIV and the size of informed return run-ups before the earnings announcements, suggesting that some traders are informed about the earnings before the public. Our approach is inspired by their suggestion that the AIV measure of information risk “may also be applied to other information events such as mergers and acquisitions, product recalls, and patent applications” (Yang et al., 2020, p. 530). We modify their measure to compare the volatility surrounding the stock transaction dates of politicians to that during the rest of the year. This modification is made because, unlike quarterly earnings, where the start of the information event is clearly defined, politicians’ trades are not necessarily the start of the event. As in Yang et al. (2020), the idiosyncratic volatility is measured on the three-factor model of Fama and French (1993).

where \(R_{i,t}\) is the daily excess return on the stock i at time t, MKT is the value-weighted market portfolio excess return over the risk-free rate, SMB is the size factor, and HML is the value factor.

To compute abnormal idiosyncratic volatility (AIV), we need to specify the time windows for the calculations. Following Ali and Hirshleifer (2017) and Yang et al. (2020), we define the 5-day window (t − 2, t + 2) surrounding the politician’s stock trade event (t) to minimize possible noise. For every transaction, we create two sub-periods. First, the around-the-trade (ATT) period includes the 5 days in the transaction window. Second, the non-around-trade (NAT) period is the whole year period before the trade, excluding the ATT days. To compute the AIV, we run the Fama–French three-factor regression for each stock using the previous year’s daily data. We obtain an estimated daily residual \(\in_{i}\) and then compute the annualized idiosyncratic volatility of stock separately for the ATT and NAT using the following formulae:

where ln stands for the natural logarithm and \(n_{ATT}\) (\(n_{NAT} )\) is the number of days in the around-the-trade (non-around-trade) period. Finally, we define the abnormal idiosyncratic volatility (AIV) as the difference between the volatility around the trade (ATT) and the rest of the year (NAT):

Note that the AIV is calculated for each stock and trade separately. This approach allows us to estimate information asymmetry associated with the transaction (i.e., the extent of political insider trading). In contrast with the previously used return analyses of politicians’ trades, the AIV-based approach captures unusual stock price patterns around their trades. Using the AIVs around the dates of politicians’ stock trades, we can detect informed trading activity by people who do not disclose their trading activity but still have access to the same information.Footnote 13

Testing Buy-and-Hold Portfolios of Political Insiders

Several papers have attempted to estimate the investment returns of politicians. For example, Ziobrowski et al. (2004) use a technique known as calendar-time transaction-based analysis (Odean, 1999). They create portfolios by purchasing stocks on the same day as the politicians, which will be then sold 12 months later. These synthetic portfolios built from politicians’ transactions outperform a passive market index by 12% per year in the Senate (1993–1998) and 6% in the House (1985–2001). However, Eggers and Hainmueller (2013) criticize their findings. Since Congress members do not hold these synthetic portfolios, the actual returns that members earned with their portfolios can be substantially different from expected returns. In addition, they note that results from such synthetic portfolios can be susceptible, and their returns can vary significantly across other specifications. Using the data before the STOCK Act, Eggers and Hainmueller (2013) show no significant outperformance of politicians.

To test Hypothesis 1 and Corollary 1 by avoiding the criticism associated with a technique that leads to the aforementioned, divergent conclusions we compute buy-and-hold market-adjusted and industry-adjusted returns over several holding periods. We follow each politician’s stock trade using information from electronic reports of senators during the January 2012–December 2019 period. For several periods of a buy-and-hold strategy, we define the buy-and-hold abnormal return on a politician’s investment as

where \(r_{i,t}\) is the daily return on firm i at time t. \(r_{mkt,t}\) and \(r_{ind,t}\) are the daily returns of S&P500 and industry, respectively. The Fama–French (1997) 48 industry classification is used to define an industry. For the period p, we consider 1w, 2w, 1 m, 2 m, and 3 m, representing periods of 1 week, 2 two weeks, 1 month, 2 months, and 3 months, respectively. We acknowledge that our empirical tests are not free from the criticism of Eggers and Hainmueller (2013). Then, the empirical version of H1 on whether or not a politician’s investment outperforms the market is

\({\text{H1}}_{0} :BHAR\left( {t,p} \right)_{i}^{mkt} \le 0\). Alternatively, \({\text{H1}}_{{\text{A}}} :BHAR\left( {t,p} \right)_{i}^{mkt} > 0\).

The empirical version of Corollary 1 for whether or not a politician’s investment exceeds the industry portfolio returns is

\({\text{C1}}_{0} :BHAR\left( {t,p} \right)_{i}^{ind} \le 0\). Alternatively, \({\text{C1}}_{{\text{A}}} :BHAR\left( {t,p} \right)_{i}^{ind} > 0\).

Based on H1 and C1, we expect four different scenarios: (1) outperforming the market and industry portfolios, (2) outperforming the market portfolio and underperforming the industry portfolio, (3) underperforming the market portfolio and outperforming the industry portfolio, and (4) underperforming the market and industry portfolios.

Note that calculating actual returns is almost impossible for two reasons. First, politicians can choose whether it is a partial sale or a complete sale when politicians report their transactions, but there are no clear definitions. Moreover, matching buys with the corresponding sales is nearly impossible because they must report ranges of total dollars invested instead of exact dollar amounts. Second, many politicians dilute their transactions, i.e., they split their purchases and sales into several smaller transactions rather than reporting one significant transaction. Hence, it is difficult to calculate the actual returns precisely, and more significant transactions could be noisy.Footnote 14

Testing Abnormal Idiosyncratic Volatility

To test H2 and H3, we employ the information risk measure of AIV with the modifications described earlier. In H2, we investigate whether the probability of informed trading (i.e., AIV) is higher during periods surrounding dates with stock transactions by senators.

\({\text{H2}}\left( {\text{a}} \right)_{0} :AIV \le 0\). Alternatively, \({\text{H2}}\left( {\text{a}} \right)_{{\text{A}}} :AIV > 0\).

As Yang et al. (2020) mention, the calculated AIV might be lower than in reality because there may be several potential events during the other period (NAT) where information asymmetry plays a role (e.g., quarterly earnings, mergers and acquisitions, product recalls, etc.).

Next, we examine whether politicians are in the first group of insiders. One can conjecture that senators are informed, but it is unclear whether they are generally among the first group of people trading on the information. To test this, we modify the computation of the AIV described earlier by shifting the five-day event window. We define \(AIV_{F}\) (i.e., politicians trade first), where the five-day window includes the transaction day and the following 4 days. Similarly, we define \(AIV_{L}\) (i.e., politicians trade last) as 4 days before the transaction and the transaction day. If politicians’ trades are genuinely in the “first wave” of informed trades, the 5-day window following their trade will contain most of the informed trades. Thus, \(AIV_{F}\) is expected to be greater than AIV. Conversely, if their trades are lagging behind those of other informed traders about a certain, \(AIV_{L}\) will present a larger value than AIV.

\({\text{H2}}\left( {{\text{b1}}} \right)_{0} :AIV_{F} \le AIV\). Alternatively, \({\text{H2}}\left( {{\text{b1}}} \right)_{{\text{A}}} :AIV_{F} > AIV\).

\({\text{H2}}\left( {{\text{b2}}} \right)_{0} :AIV_{L} \le AIV\). Alternatively, \({\text{H2}}\left( {{\text{b2}}} \right)_{{\text{A}}} :AIV_{L} > AIV\).

Data and Descriptive Statistics

We use data from the United States Senate Financial disclosures (https://efdsearch.senate.gov/), which started in 2012 following the STOCK Act. Senators have an option to either (1) report their transactions on a paper form that is then scanned and made available online or (2) fill it out electronically (See Fig. A1 as an example of the electronic reports). They have 30–45 days to report each transaction and generally do this in batches rather than individually.Footnote 15

From the electronically filed reports, we can identify the type of investment, whether the asset was bought or sold, whose account was used for the trade, the range of dollar value of the transaction, and the security. The final dataset contains 8064 total transactions, with 7092 stocks, 67 non-public stocks, 13 stock options, 319 municipal securities, 288 corporate bonds, and 285 other securities (See Table 1). The electronic version of the reports covers the transactions of 49 different senators, 22 Democrats, and 27 Republicans. The average tenure is 11.5 years, and 47% of these senators were members of the House previously. As part of the STOCK Act, records are only kept for 6 years after retirement. Therefore, no transaction records are available for the senators who retired many years ago. Accordingly, we mostly skip or interpret results for 2012 and 2013 with caution because of the meager number of observations (5 in 2012 and 19 in 2013).Footnote 16

Table 1 depicts the distribution pattern of transactions by type of security and direction of the trade over the years, where Panel A shows the total number of trades and Panel B shows the percentage of the total transaction for the given type of security and direction of the trades. Again, we observe that there are very few observations in 2012 and 2013.

The number of transactions is not very stable through the years. The dip in transactions in 2016 could be the uncertainty about the presidential election and the power shift in the political landscape. A similar reason may apply to the drop in 2019 when rising uncertainty led more traders to adjust their portfolios toward less risky assets. This is supported by the evidence in Panel B of Table 1, where we observe the highest percentages of purchases of municipal (44.4%) and corporate bonds (21.3%) during the sample period.Footnote 17 Since many analysts were predicting a stock market crash and recession in 2019, senators might have become more conservative in their investments.

Additionally, it is plausible that senators may have been reluctant to take advantage of some specific economic situations such as recessions because they might trigger greater public scrutiny. This is a reasonable explanation based on a recent incident. Prior to the COVID-19 lockdowns, the senate committees on health and foreign relations had a meeting where they were informed on how the COVID-19 outbreak would affect the country and financial markets. Following the meeting, they made many transactions to sell their stocks, leading to an investigation by the ethics committee (Ziolkowski, 2020).

As part of the STOCK Act, even senators’ immediate family members need to report their transactions following the same format. The internet appendix (Table 12) reports the distribution of senators’ trades by security types. Our findings show that most transactions happen on joint accounts, followed by spousal accounts, self-accounts, and child accounts. This result supports Karadas’ (2018) findings, which suggest that senators’ spouses might trade based on insider information. While this may indeed be the case, it could also indicate that politicians may use their spouses’ accounts to conduct some of their trades, hoping to keep a low profile, as the spouses’ trading history may not be followed as closely as their own.

Next, we compare diluted versus non-diluted transactions. For a transaction to be classified as diluted, either a senator has made several transactions involving the given security on the same day, or she has traded the same security in immediately subsequent trading days. We observe that 45% of transactions were diluted. On the one hand, this pattern could be consistent with politicians’ use of the noise caused by uninformed traders to make a profit on their insider information without alerting the market, which is in line with the model of Kyle (1985). Or politicians’ desire to mask total investment size makes it hard for observers to calculate actual returns. On the other hand, this pattern of diluted transactions could reflect senators’ attempt to lower the average cost per share.

We should note that there might be even more diluted transactions than we are catching. For example, there could be transactions that are a day (or more) apart but made with the same intentions in mind. However, extending the possible time window associated with defining diluted transactions raises the chance of increasing the noise in the data. Therefore, we restrict the time window to only consecutive trade days.

The pattern of the diluted trades over the years is unclear. However, their number is likely affected by political uncertainty and pushed by legislative activity, which provides a foundation for inside political information. For example, election years are characterized by more diluted trades than non-election years. This suggests that the dilution could be correlated with potential insider trading because it serves as a tool to mask the trading activity. We will examine these issues in more detail later.

Empirical Results

Buy-and-Hold Stock Returns Following Senator’s Trades

To examine buy-and-hold excess return (market), we conduct two tests for mean values (t tests) and median values (sign tests). H1 is set to test whether stock returns outperform the market in each given year and for each holding period commencing with the day of a senator’s trade. In Table 2, the first set of rows tests whether the average abnormal return is different from zero, while the second set of rows contains the sign tests (also known as the median tests).

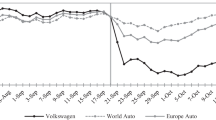

Overall, Table 2 results reject the first null hypothesis (H10) and support H1A, which states that politicians’ buy-and-hold returns outperform the market. Except for the shortest holding period, we find evidence that senators’ stock purchases outperform the market at the 1% significance. The average buy-and-hold abnormal return (market) is about 0.5% for two weeks and increases to 4.9% for 3 months.

When we analyze the patterns of the excess market returns by year, we still observe that the averages are positive and significant at a 1% level in most cases. However, a few negative and significant excess returns are present for some holding periods in 2015 and 2018. We also note that in both 2015 and 2018, the largest portion of stocks was sold, and most transactions were diluted.Footnote 18 In addition, we examine excess returns using a different benchmark such as CRSP value-weighted market index and find that the results remain the same.

Overall, the observed patterns of the abnormal market returns are amplified with the more extended hold periods. This longevity suggests that value-relevant political information may take a while to become incorporated into stock prices. Moreover, a non-parametric version of our test procedure, the sign test of Snedecor and Cochran (1989), confirms and magnifies the results of the t tests. Thus, the combined results do not support the prediction based on the social contract theory.

We examine industry-adjusted returns for stock purchases and report the results in Table 3. The mean excess returns are not significantly different from zero for a large portion of the results. The lack of significance for the t test could be explained by the high variation of the excess returns (industry). On average, outperforming the industry portfolio would be less common than outperforming the market since corporate insider information is primarily available only to a limited number of senators who, for example, may sit on essential committees and observe corporate lobbying activities (Eggers & Hainmueller, 2014). Thus, the results of industry-adjusted returns are not conclusive.

Abnormal Idiosyncratic Volatility

This section aims to analyze if politicians’ trades are associated with periods of higher information asymmetry. Since such information asymmetry cannot be simply attributed to a few recorded politicians’ transactions, high AIV values during periods around politicians’ trades would imply that either many more people at Capitol Hill are relying on the inside political information or this valuable inside information could be leaked to other market participants. Accordingly, we test H2 by the decomposition of factors that drive abnormal idiosyncratic volatility (AIV).

Table 4 below contains mean AIVs based on a 5-day window around the stock trade across years and different types of characteristics. For the sake of space, we report only the 5-day results, but the complete set of results using alternative windows is available upon request. We find that information asymmetry associated with stock trades by senators is considerably high. It is, on average, 3.6%, which is higher than the average AIV of 1.1% related to quarterly earnings announcements in Yang et al. (2020). Thus, our results on the AIV do not support the social contract theory prediction of H2. Table 4 presents the average value of the AIV computed across years, personal characteristics, and account types. The highest AIV is associated with the joint accounts (9.7%), followed by spouse-owned accounts (−1.8%), and self-owned accounts (−3.0%), with the child accounts representing a very low (large negative) value of the AIV (−12.5%). These results suggest that politicians may refrain from using their self-owned accounts when trading based on potential insider information. A child’s account is also limited, unlike corporate insider trading found in Berkman et al. (2014). Berkman et al. (2014) find that the guardians behind under-aged accounts successfully pick stocks. Moreover, they show that the guardians tend to channel their best trades through children’s accounts.

Regarding the direction of trade, we observe that partial sales are associated with a higher AIV even when compared to purchases. This could, however, be caused by the lack of legislative activity in 2014, when the mean AIV for purchases was low (and negative). Moreover, senators can use their insider information to minimize losses. For example, in early 2020, senators with access to information about the incoming measures against COVID-19 took their money out of the market (Ziolkowski, 2020).

The effect of diluted transactions could be more complex because of a wider window and a higher noise associated with diluted dealings. The results are very similar when we use other windows (e.g., 7 days) for the calculation of AIVFootnote 19 but with lower mean values, suggesting that increasing the time window prevents us from capturing more information asymmetry and raises the noise in the measurement.

One potential problem with interpreting an increase in the AIV around politicians’ trades as evidence of political insider trading could be related to other major corporate announcements on dividends, earnings, mergers and acquisitions, and stock repurchases. These events may convey no important political information but lead to high AIV. We examine the frequencies of trades made during the major firm-specific announcements to verify if this is the case. Thus, we want to compare how the information asymmetry during the senator stock transaction period to that around quarterly earnings announcements.

In Table 5, we report that these events, on average, represent only around 4.2% of the overall senators’ trades. Moreover, we conduct an additional test after removing the transactions that occur during the events and find that our results are similar to those obtained from the whole sample, presented in the following sections.Footnote 20

Alternative Measures of Abnormal Idiosyncratic Volatility

In this section, we define modified versions of the AIV to analyze if politicians are in the first wave of informed traders and to compare the extent of the AIV associated with the politician’s trade with the AIV connected with the quarterly earnings, as defined by Yang et al. (2020). First, we calculate AIV around the quarterly earnings for every year and the stock for which a senator transaction occurred. We denote this abnormal idiosyncratic volatility as \(AIV_{E}\) (earnings) to differentiate it from other calculated measures. To test H2(b1) and H2(b2), we define \(AIV_{F}\) (first informed) and \(AIV_{L}\) (last informed) using different event windows.

Given the fact that while AIV, a price-based measure of informed trading, in the context of Yang et al. (2020), is measured surrounding a widely announced corporate event (i.e., earnings report), there is a caveat concerning the AIV measured around a very quiet (non-public) senator trade as a proxy of information asymmetry. Market microstructure literature has introduced several quantity-based measures of asymmetric information, the most prominent of which is the Easley et al. (1996) measure of Probability of Informed Trading (PIN) and the closely related VPIN measure of Easley et al. (2012). Although these measures have also been criticized in the literature,Footnote 21 they could allow us to test the robustness of our findings using the quantity-based measures of informed trading. Unfortunately, we lack access to the high-frequency trading data necessary to construct the PIN (or VPIN) measure. Instead, we construct three alternative proxies for information asymmetry, which have been used in prior literature (e.g., Brennan & Subrahmanyam, 1996; Armstrong et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2020). Spread is computed as (asking price–bidding price)/traded price, multiplied by the number of trades. Abnormal volume is computed as in Yang et al. (2020). We compare trading volume (in millions) in the 5-day window surrounding the politician’s trade to trading volume in the rest of the year as we did for AIV. Abnormal turnover is the difference in turnover (= trading volume/shares outstanding) between the 5-day window and the rest of the year. We observe that these proxies are highly correlated with AIV.

In Table 6, we show the means of the AIV, \(AIV_{F}\), and \(AIV_{L}\) along with \(AIV_{E}\) throughout the years. The highest AIV is associated with the regular definition of the AIV, followed by \(AIV_{L}\) and then by \(AIV_{F}\). This evidence suggests that senators are in the middle of the pack of informed traders and rarely the first or the last to trade on the news, negating H2(b1) and H2(b2).

The observed differences across years could partly be due to different levels of legislative activity or changes in the ruling party/administration. For example, the lowest level of legislative activity is found in 2014, implying the least amount of potential political inside information available to senators. This explains the negative mean values of the AIV in 2014. In 2017, the first year of the Trump administration, information that could affect the market might have been driven mainly by the president himself, potentially leading to the observed negative values for AIV.

To formally test H2(b), we use both the t test and the sign test, as in the previous section. We report the battery of tests in Table 7, documenting the differences between the average values of various AIVs. It confirms that the regular AIV has the highest values. We also observe that the AIV associated with politicians’ trades is higher than that around earnings announcements (\(AIV_{E}\) as defined in Yang et al., 2020). This result implies that, on average, information asymmetry is greater during periods around senator transactions than during periods around quarterly earnings announcements. More importantly, this result supports our view that there is a flow of valuable private information from Capitol Hill and that senators’ trading activity is only the tip of the iceberg. Most individuals who have access to the information do not have to report their investments. We also find that three alternative variables present similar patterns. Similar to AIV measures, the average values are relatively higher in 2015, 2016, and 2018 and lower in 2014 and 2017.

Determinants of Political Information Risk and Politicians’ Stock Performance

We now estimate the regression models of political information risk (AIV) and politicians’ stock trade performance (buy-and-hold returns). Again, our stock performance analysis does not extend over periods longer than 3 months as in other tests. Both models include an extensive list of standard control variables. Still, our focus is on political variables (i.e., politicians’ personal and legislative characteristics) that may reveal possible channels for the information asymmetry around senators’ stock transaction dates.

Several variables are related to Senate legislative activity. The Legislative effectiveness score (LES)Footnote 22 measures how well the senator advances her agenda items through the legislative process and into law. A high LES score implies that the senator has greater influence and better connections within the U.S. Senate (Fowler, 2006a, 2006b) and is better informed. Senators can also gather information by serving on various committees. With better access to important news (e.g., on the policy agenda in general or specific pieces of legislation) and with the benefit of observing relevant individual firm lobbying, committee service can give them further valuable insight (Eggers & Hainmueller, 2014). To capture this effect, we include five committees based on the power ranking defined by Stewart (2012): Finance, Appropriations, Rules and Administration, Armed Services, and Foreign Relations. We include the Number of bills lobbied for (reported in hundreds) and the Number of lobbyists on the day of the transaction (reported in thousands) to explain the importance of the current legislative events. For every transaction date, we sum the number of introduced bills that have at least one lobbyist.

Additionally, we sum the total amount of lobbyists across all bills introduced on the transaction date. Finally, there is some evidence that investments in local firms could result in higher returns (Eggers & Hainmueller, 2014). We, therefore, include the Home bias indicator variable equal to 1 when a senator’s stock trade involves a firm from their home state and 0 otherwise. We also add two industry-related variables. Industry concentration is the value of the Herfindahl index that is computed by each firm’s total stock value within the same industry. The weight of each stock in the given industry based on stock value is included.

As firm controls, we employed standard variables used in asset pricing models: Past profitability, Illiquidity, Firm size, Book-to-market ratio, and Beta. Past profitability is measured using four separate past stock returns, following Brennan et al. (2012). Similarly, we use a group of variables \(R_{m - 1} , R_{{\left[ {m - 3,m - 2} \right]}} , R_{{\left[ {m - 6,m - 4} \right]}} , R_{{\left[ {m - 12,m - 6} \right],}}\) which stand for returns over the last month, previous months 3–2, previous months 6–4, and previous months 12–6, respectively. Illiquidity is measured following Amihud (2002) as a sum of absolute values of daily returns divided by daily volume for the year, multiplied by 10^6. Firm size is the log of the market value of equity. The book-to-market ratio is the log of the book-to-market ratio. Beta is calculated using the Fama–French (1993) three-factor model over the past 6 months. However, Beta is only used as a control variable for the AIV regression. We provide detailed descriptions (Table 11) and summary statistics (Table 14) in the internet appendix.

In Table 8, we report results for three AIV regression specifications. Column (1) contains both tenure and age variables. In column (2), we omit the tenure and keep the age variables. This alternative specification serves as a sensitivity check since tenure and age are highly correlated. Finally, in column (3), we use a subsample that includes only stock purchases. Table 8 reveals some interesting results. First, senator tenure and age are the only personal characteristics that remain statistically significant when we include the other control variables. Specifically, early-career and mid-career senators’ trades generate significantly higher informed trading than late-career senators. More specifically, in column (1), senators with shorter tenure (0–4 years) present an 11.8 percentage points higher AIV, on average, than senators with longer tenure (14–35 years).

The Number of bills coefficient is positive and significant at the 5% level, suggesting that higher levels of overall legislative activity generate more insider information, increasing information asymmetry. The coefficient of Finance Committee (the most powerful committee based on the ranking in Stewart (2012)) is also positive and significant. This indicates that trades by the finance committee members are significantly more informative than the rest, suggesting that such a committee might be privy to a substantial amount of value-relevant information.

The negative Home bias effect may appear surprising at first glance. However, this effect may imply that senators may be reluctant to widely share insider information about firms in their home state. As mentioned previously, the AIV captures the abnormal stock activity resulting in departures from the Fama–French asset pricing model. Therefore, changes in AIV cannot merely be caused by a few reported trades but rather require substantial additional trading activity. Hence, we would not detect information asymmetry when inside information is available to a limited number of market participants. Alternatively, the negative coefficient of Home bias may indicate that senators deliberately avoid trading on insider information about home state firms.

We see that the Number of lobbyists has a negative and significant effect on AIV, which is consistent with the view that lobbyists reduce information risk by disseminating value-relevant information to the market. In sum, information risk around senator stock trade dates appears to increase with the senatorial activity (Number of bills) and decrease with lobbying activity (Number of lobbyists). Thus, overall, we have some supporting but mixed evidence of H3.

Industry concentration is positively related to AIV. The estimated coefficient is consistently significant across three models at the 1% level. We interpret this as evidence that, if a few large firms dominate the industry, there are a number of small-sized firms that tend to present high levels of information asymmetry.

Note that stocks with many politicians’ trades over the past year would have fewer NAT days by construction. This feature could potentially distort the value of AIV and hence consequently affect the results. To account for this data-specific aspect and test our results’ robustness, we also run a weighted OLS regression, using the ratio of NAT days to ATT days as weights. The results are similar to those in the main specification, showing that our results are not biased by a larger number of ATT days. The detailed results are not presented here; they are available in the internet appendix (Table 15).

Now, we will analyze the abnormal market returns to determine the main drivers of individual profitability for the other stock purchases. Table 9 Panel A depicts the market-adjusted buy-and-hold returns analysis results for the five different periods over 3 months. Interestingly, stocks bought by early- or mid-career senators have higher market-adjusted returns over longer holding periods. Contrary to the AIV regressions, age is a positive and significant predictor of future returns. These results can suggest that older senators’ trades are associated with more information asymmetry, but the younger senators are making more profitable investments.

The legislative effectiveness score (LES) coefficient is not significant for the short holding period models but turns positive and significant for the more extended period models (≥ 1 month). This suggests that senators who are better connected within the legislative network may possess information that takes at least 2 months to be incorporated into market prices. Home state stocks bought by senators also perform significantly better over more extended holding periods, which supports the findings of Eggers and Hainmueller (2014). Coupled with the fact that the trades of home state stocks are associated with lower AIV (reported in Table 8), this result implies that senators may not share value-relevant information about home state firms with many others. We find that AIV is a significant and positive predictor of two-week and 1-month returns. Interestingly, this time period is matched with a period of 30–45 days for senators to report their transactions.

In addition, we analyze the industry-adjusted returns and report the analysis in Table 9 Panel B. The results are generally consistent with the market’s abnormal returns. We observe that politicians with a high Legislative effectiveness score (LES) outperform even the industry for longer term periods. Furthermore, we find that both home bias and AIV remain strong predictors of industry-adjusted returns. These results suggest that even though senator trades, on average, do not outperform the industry portfolios, there might be some specific instances where senators will have a superior stock picking ability.

Overall, our buy-and-hold returns analysis nicely complements the findings of AIV regressions. Our results show that senators’ stock trading activity reported in electronic filings is information-driven and that the magnitude of information asymmetry predicts future returns. Nevertheless, the politically informed trading we uncover could be the tip of the iceberg since many more people have access to the same information but do not have to file their trades.Footnote 23

Sale Transactions

While purchases signal a positive view of the stock, sales trades include a more complex and diverse set of possible motivations. For example, the decision to sell could not only be driven by negative information but more commonly, by liquidity needs or by the decision to secure a profit or minimize a loss. Moreover, the timing of a sale can be distorted by decision bias like the disposition effect.

The STOCK Act does not require senators to report the exact amount invested or the price at which they purchased (and sold) the security, making it impossible to accurately calculate realized returns on their investments. This, in turn, makes it hard to disentangle the different motives for selling thoroughly. As a result, even though there are documented cases of senators’ informed selling to protect their investments (e.g., selling their stocks before the incoming measures against COVID-19), proper identification of such a subsample of sales transactions remains elusive given the current data. Moreover, the analysis of sale transactions needs to be performed separately using different methods. It is because neither buy-and-hold of stocks after senators’ stock sales nor a portfolio analysis after selling by senators (as reported by Eggers & Hainmueller, 2013) can distinguish among sales motivated by insider information, disposition effect, liquidity-based trading, or other motivations.

Table 10 provides a robustness test of politicians’ stock trade performance using an alternative measure based on the premise that the average sale should be less informed than the average purchase trade. We match every purchase transaction with the most recent sale transaction by the same politician that occurred within a week of the purchase. We then compute the difference of the market-adjusted returns by subtracting the return of the stock the senator sold from the return of the stock just purchased.Footnote 24

Therefore, positive and significant returns would suggest that stocks that senators purchase perform better than those they just sold. We conduct two tests for mean values (t-tests) and median values (sign tests) to examine this. For the mean value tests, the t tests show that returns are higher after the purchases in general (except in 2014), and the effect increases with the longer holding periods. The median tests (sign tests) also present similar patterns. Consequently, we conclude that the primary reason for selling stocks is to secure profits and reserve liquidity for the next investments. That is, sale transactions may not be driven by negative stock information. We leave a more rigorous analysis of sale transactions for future research.

Summary and Conclusions

This paper suggests that political insider trading is unethical as it appears to expropriate other stakeholders’ expenses by exploiting information advantages gained through political position or connection (Bhattacharya & Daouk, 2002; Christensen et al., 2017; Gao & Huang, 2016). Its unethical nature is mainly due to conflict of interest and could raise social distrust.

We analyze electronic filings of stock trades made by senators in compliance with the STOCK Act to test whether politicians and their networks (i.e., staff, lobbyists, other- home state- legislators, and others) use political insider information in their investment decisions. First, we confirm politically informed trading by employing a buy-and-hold return analysis for stocks purchased by senators, a departure from the synthetic portfolio analysis used in prior studies. Moreover, we propose a modification of the abnormal idiosyncratic volatility (AIV), initially introduced by Yang et al. (2020), to measure the extent of information risk associated with periods around politicians’ trades. This approach allows us to capture possible (mis)use of inside political information for a much broader set of political actors, who may possess the same information as the senators in our sample but are not required to file reports on their stock trades. Thus, using the AIV measure is a noble method in that we are able to estimate the degree of politicians’ information asymmetry and test the validity of the social contract theory.

We show that information asymmetry associated with stocks traded by senators is, on average, relatively high (3.6%) and driven by the senator’s access to legislative information acquired by being an effective legislator or member of an important committee. The results suggest that the social contract theory is not supported by the results in our information asymmetry tests. In addition, our analysis confirms that information risk is elevated (attenuated) on days when there is a lot of legislative (lobbyist) activity. Lastly, we show that investing in the stock of a company headquartered in the senator’s state can yield high and significant returns, especially for more extended holding periods. Moreover, these trades are associated with significantly lower levels of AIV, suggesting that perhaps senators refrain from sharing value-relevant information with a broader set of associates.

Overall, our results showing high AIV around politicians’ trades support the view that senators’ use of inside political information represents only the tip of the iceberg. Many more legislators, politicians, and selected market participants have access to the same information but do not file their returns. We also believe that our results could shed more light on the puzzle of observed negative AIV values associated with some earnings announcements. If we purge periods surrounding politicians’ trades, obtaining a cleaner measure of AIV around corporate information events such as earnings announcements might be possible. Finally, our evidence refutes the social contract theory’s view of political insider trading. It suggests that there needs to be further discussion and deliberation leading to legislation further improving the STOCK Act.

Notes

There is a plethora of popular press articles on politicians’ trading occurring prior to major news announcements. Some examples include the recent covid-19 onset and related lockdowns (e.g., see https://www.thedailybeast.com/sen-kelly-loeffler-dumped-millions-in-stock-after-coronavirus-briefing; https://www.ajc.com/news/state--regional-govt--politics/david-perdue-stock-trading-saw-uptick-coronavirus-took-hold/MRWmzwXeHgxi6IcmBbPgaN/; https://www.businessinsider.com/coronavirus-david-perdue-bought-stock-company-producing-ppe-after-briefing-2020-4; https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/20/coronavirus-gop-sen-hoeven-bought-up-to-250000-in-health-fund-after-briefing.html; https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2020/03/burr-unloaded-stocks-before-coronavirus/), failed drug trials (e.g., https://nypost.com/2018/08/08/gop-congressman-busted-for-insider-trading/), the invasion of Ukraine by Russia (https://finance.yahoo.com/news/10-stocks-us-politicians-bought-164447897.html), or upcoming Obama Care legislation (https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970204844504577100260349084878).

Some studies show that investments by members of Congress outperform the market (Gao and Huang 2016; Jeng et al., 2003; Ziobrowski et al., 2004), presumably due to their significant informational advantage (Gao and Huang 2016; Ziobrowski et al., 2004). On the other hand, others suggest that stocks purchased by senators, on average, underperform the market (Belmont et al., 2020; Eggers and Hainmueller 2013). For instance, using portfolio analysis, Ziobrowski et al. (2004) show that government insiders outperform the market by 10% per year on average. Christensen et al. (2017) find more profitability from the recommendation revisions issued by analysts who are employed at politically connected brokerage houses.

In his 2011 testimony on the STOCK Act proposal, Robert Khuzami states that “[t]here is no reason why trading by Members of Congress or their staff members would be considered “exempt” from the federal securities laws, including the insider trading prohibitions, though the application of these principles to such trading, particularly in the case of Members of Congress, is without direct precedent and may present some unique issues.” See https://www.sec.gov/news/testimony/2011/ts120611rk.htm.

As described in Christensen et al (2017) political information encompasses “information about many types of issues, such as prospective legislation, upcoming government actions (e.g., interest rate cuts, military strikes), failed negotiations with other countries, unfolding economic crises (e.g., Great Recession), etc.”.

For example, a 2013 Washington Post article states: “An April 1 alert to stock traders that predicted the outcome of a key Medicare funding decision has gained intense legal and public scrutiny. But a series of events in Washington and on Wall Street in the weeks before the alert raises the possibility that information related to the government’s decision may have previously circulated and moved the market, according to a trail of e-mails and market data.” (ElBoghdady and Hamburger 2013).

In our application, we focus on senators because past results indicate that senators tend to perform better than representatives (e.g., Kim 2013a). In general, senators are more experienced and powerful, and they are better able to obtain inside information.

The theory of virtue ethics (Aristotle 1926; Klaw and Mayer 2021; Maclntyre 1984, 1988; Murphy 1999) might be a plausible alternative perspective to the social contract theory, but nevertheless less suitable for interpreting empirical results as it does not have an accurate prediction of abnormal returns or information asymmetry.

There were more than 7000 legislators in 2012 that had access to political insider information and could still trade on it without any repercussions after the passing of the STOCK Act (Kim 2013c). Currently, congressional aides and staffers do not have to disclose their trading activities (Lawder and Cowan 2012).