![header=[Marker Text] body=[Organized in 1833 by Quaker abolitionist Lucretia Mott, this society, headquartered here, originally consisted of sixty women who sought to end slavery. After the Civil War, the society supported the cause of the freed slaves. ] sign](http://explorepahistory.com/kora/files/1/10/1-A-105-139-ExplorePAHistory-a0a4h2-a_450.gif)

Mouse over for marker text

Name:

Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society

Region:

Philadelphia and its Countryside/Lehigh Valley

County:

Philadelphia

Marker Location:

5th & Arch Streets, Philadelphia

Behind the Marker

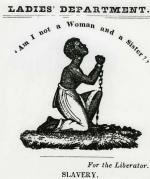

When William Lloyd Garrison, the editor of the nation’s leading abolitionist paper, The Liberator, called for the organization of an American Anti-Slavery Society to take place in Philadelphia in the first week of December 1833,  Lucretia Mott was thrilled. As women, she and Lydia White, Esther Moore, and Sidney Ann Lewis could not be delegates, but they were permitted to observe the proceedings from the gallery. To the surprise of many, Mott asked the chairman if she could to speak, and then addressed the delegates on several points. At the end of the meeting, as the delegates were deciding whether or not to sign the “Declaration of Sentiments,” Mott instructed her husband: "James, put down thy name!"

Lucretia Mott was thrilled. As women, she and Lydia White, Esther Moore, and Sidney Ann Lewis could not be delegates, but they were permitted to observe the proceedings from the gallery. To the surprise of many, Mott asked the chairman if she could to speak, and then addressed the delegates on several points. At the end of the meeting, as the delegates were deciding whether or not to sign the “Declaration of Sentiments,” Mott instructed her husband: "James, put down thy name!"

Impressed by Mott’s thoughtful words recommending several amendments to the declaration and by the commitment of the four women in attendance, the members of the new American Anti-Slavery Society formally encouraged the creation of a female antislavery society. Just three days later, on December 9, 1833, Mott and twenty-one women met in a Philadelphia schoolroom to found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS). On December 14, they finalized their Constitution. "We deem it our duty, as professing Christians," they resolved, "to manifest our abhorrence of the flagrant injustice and deep sin of slavery by united and vigorous exertions."

From the beginning, the Society was interracial, its members including African-American businessman James Forten's three daughters, Margaretta, Sarah, and Harriet, who was married to black abolitionist

James Forten's three daughters, Margaretta, Sarah, and Harriet, who was married to black abolitionist  Robert Purvis.

Robert Purvis.

The women of the PFASS immediately got to work. Within a year they had collected funds to run their group, subscribed to anti-slavery publications, established a school for African Americans, and begun to promote the boycott of goods manufactured by slaves. They also began lobbying for emancipation. In 1836 they sent a petition to Pennsylvanian Senator Samuel McKean and Congressman James Harper to present to Congress. “I have received your petition bearing the signatures from 3,300 women of Philadelphia and I will present it,” McKean wrote to them. “But you cannot be ignorant of the extreme sensibility of the subject.”

In the 1830s, slavery was increasing polarizing the nation. Living in a border state with many economic and social ties to the South, Pennsylvanians were deeply divided in their attitudes towards slavery, race relations, and the women who were actively participating in the growing abolition movement. In 1837 the state legislature stripped black Pennsylvania men of their right to vote, a right they had held since 1776. That same year Lucretia Mott, Mary Grew, and Sarah Pugh joined the executive board of the newly formed the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1837.

The growing tensions over race and gender exploded into violence in May 1838, when the second Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women held their second national meeting in Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Hall. On May 17th, a huge mob of pro-slavery protestors, enraged by the presence of white women publicly interacting with both men and African Americans, burned the hall to the ground.

Pennsylvania Hall. On May 17th, a huge mob of pro-slavery protestors, enraged by the presence of white women publicly interacting with both men and African Americans, burned the hall to the ground.

The burning of Pennsylvania Hall, however, failed to slow the abolition movement, or the members of the PFASS, who focused more and of their efforts on raising funds for the abolition movement and the emerging Underground Railroad through the staging of annual fairs. Following the lead of the Boston Female Anti-slavery Society, the PFASS held its first fair in 1836, selling baked goods, needlework, art pieces, and pottery with anti-slavery designs. In the years that followed the fairs grew in size and scope.

From 1836 to 1854 the PFASS donated $13,845—the rough equivalent of close to $400,000 today-- to the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, and also supported the Underground Railroad through its contributions to the Philadelphia Vigilant Committee, organized in 1837 by Robert Purvis to aid escaped slaves in southeastern Pennsylvania. The women continued their support even after doing so became illegal with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Members of the PFASS also contributed to the housing, protection, and transportation of escaped slaves.

During the Civil War, Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society members devoted their efforts to the support of the war effort, and after the end of slavery in 1865 to the campaign for African Americans’ right to vote. The Society organized its final fair, to support the movement for black suffrage, in 1869, then disbanded in 1870 after ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment.

Impressed by Mott’s thoughtful words recommending several amendments to the declaration and by the commitment of the four women in attendance, the members of the new American Anti-Slavery Society formally encouraged the creation of a female antislavery society. Just three days later, on December 9, 1833, Mott and twenty-one women met in a Philadelphia schoolroom to found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS). On December 14, they finalized their Constitution. "We deem it our duty, as professing Christians," they resolved, "to manifest our abhorrence of the flagrant injustice and deep sin of slavery by united and vigorous exertions."

From the beginning, the Society was interracial, its members including African-American businessman

The women of the PFASS immediately got to work. Within a year they had collected funds to run their group, subscribed to anti-slavery publications, established a school for African Americans, and begun to promote the boycott of goods manufactured by slaves. They also began lobbying for emancipation. In 1836 they sent a petition to Pennsylvanian Senator Samuel McKean and Congressman James Harper to present to Congress. “I have received your petition bearing the signatures from 3,300 women of Philadelphia and I will present it,” McKean wrote to them. “But you cannot be ignorant of the extreme sensibility of the subject.”

In the 1830s, slavery was increasing polarizing the nation. Living in a border state with many economic and social ties to the South, Pennsylvanians were deeply divided in their attitudes towards slavery, race relations, and the women who were actively participating in the growing abolition movement. In 1837 the state legislature stripped black Pennsylvania men of their right to vote, a right they had held since 1776. That same year Lucretia Mott, Mary Grew, and Sarah Pugh joined the executive board of the newly formed the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society in 1837.

The growing tensions over race and gender exploded into violence in May 1838, when the second Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women held their second national meeting in Philadelphia’s

The burning of Pennsylvania Hall, however, failed to slow the abolition movement, or the members of the PFASS, who focused more and of their efforts on raising funds for the abolition movement and the emerging Underground Railroad through the staging of annual fairs. Following the lead of the Boston Female Anti-slavery Society, the PFASS held its first fair in 1836, selling baked goods, needlework, art pieces, and pottery with anti-slavery designs. In the years that followed the fairs grew in size and scope.

From 1836 to 1854 the PFASS donated $13,845—the rough equivalent of close to $400,000 today-- to the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, and also supported the Underground Railroad through its contributions to the Philadelphia Vigilant Committee, organized in 1837 by Robert Purvis to aid escaped slaves in southeastern Pennsylvania. The women continued their support even after doing so became illegal with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. Members of the PFASS also contributed to the housing, protection, and transportation of escaped slaves.

During the Civil War, Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society members devoted their efforts to the support of the war effort, and after the end of slavery in 1865 to the campaign for African Americans’ right to vote. The Society organized its final fair, to support the movement for black suffrage, in 1869, then disbanded in 1870 after ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment.

Beyond the Marker

![A Group of Philadelphia Abolitionists with Lucretia Mott [seated second from the right]. A Group of Philadelphia Abolitionists with Lucretia Mott [seated second from the right].](http://cache.matrix.msu.edu/expa/small/1-2-1BA3-25-ExplorePAHistory-a0n0v8-a_349.jpg)