Japanese American Relocation

After the Japanese Imperial Navy attacked US forces at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, bringing the United States into World War II, fear of espionage or sabotage by people of Japanese ancestry gripped the country. In the aftermath of the attack, the US government relocated approximately 120,000 people of Japanese descent—mostly American citizens—from their West Coast homes to “relocation centers” in remote areas of the country.

-

1

In 1940, approximately 127,000 persons of Japanese descent lived in the continental United States.

-

2

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which gave the Secretary of War the authority to exclude “any and all persons” from entering, remaining, or leaving designated military areas.

-

3

The executive order provided US military commanders with the power to legally and forcibly relocate some 120,000 Japanese and Japanese Americans from their homes on the West Coast to inland relocation centers.

Note on Terminology

Words used during the 1940s to describe Japanese relocation were often misleading and intended to sound benign or even helpful to those individuals who were being forcibly removed from their homes. Terms like “evacuation” and “exclusion” masked the reality of forced removal. Some Japanese Americans today prefer using the terms “concentration camp” and “incarceration” to “relocation camp” and “internment.” (The word “internment” should be used to describe legally permissible detention of enemy aliens, and therefore does not properly describe the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans, most of whom were US citizens.)

The camps were sometimes called “concentration camps” during the war, though after the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps, the phrase tended to be associated with Nazism rather than with incarceration of Japanese Americans.

During World War II, Americans often used the derogatory word “Jap” to describe people of Japanese descent. That term is now considered an offensive ethnic slur.

Historical Context

The United States had a history of racist laws against people of Asian descent before World War II. In the mid-19th century, some Americans believed that the influx of immigrant Chinese laborers, most of whom built railroads, competed with Americans for jobs. Popular newspapers of the time coined the phrase “Yellow Peril” to convey the “threat” these immigrants posed, not just to the labor market but also to the nation’s “racial stock.”

These fears helped to support a series of laws meant to limit—or block entirely—Asian immigrants from coming to the United States. In 1882, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which forbade any new immigration from China, and, in 1907, the “Gentleman’s Agreement” limited the ability of Japanese citizens to enter the United States. The 1917 Immigration Act expanded these restrictions by creating an “Asiatic Barred Zone,” a large area encompassing most of central Asia, and including India, the Arabian Peninsula, and Pacific Islands, from which immigration to the United States was forbidden. The 1924 Johnson-Reed Immigration Act placed an overall limit of 1,424 immigrants per year from the areas of Asia where immigration had not already been banned. Under these racist laws, no one born in Asia could become a naturalized United States citizen, unless the US government decided that he or she was white.

Japanese Americans in the United States

By 1940, most Japanese immigrants and their descendants lived on the West Coast, especially in California. While US laws had limited immigration from most of Asia, Japanese arrivals in the territory of Hawaii were largely unrestricted, since Hawaii was not yet a US state. About 158,000 people of Japanese descent lived there, making up 40% of the total population of the islands. Japanese in the continental United States called themselves: Issei (“first generation,” or immigrants) and Nisei (“second generation,” or children of immigrants). The approximately 47,000 Issei were born in Japan, and US law barred them from becoming American citizens. The 80,000 Nisei, the children of Issei, were born in the United States and were American citizens.

Impact of Pearl Harbor

Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor, many Americans worried that Japanese Americans were disloyal to the United States. As US relations with Japan deteriorated, President Franklin D. Roosevelt commissioned a secret study of the “Japanese situation” on the West Coast, to see if people of Japanese descent would pose a threat in the event of war with Japan. Roosevelt’s investigator, Curtis B. Munson, determined that more than 90% were loyal to the United States.

The Japanese Imperial Navy launched a surprise air attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and other US bases in the Pacific on December 7, 1941. The Japanese American community quickly experienced an increase in racism. Popular magazines included drawings to help Americans distinguish between people of Chinese ancestry, American allies, and people of Japanese ancestry, whose loyalty was in doubt. The governor of Idaho, Chase A. Clark proposed that “A good solution to the Jap problem would be to send them all back to Japan, then sink the island. They live like rats, breed like rats, and act like rats.” Congressman John E. Rankin of Mississippi declared: “This is a race war. . . . I am for catching every Japanese in America, Alaska, and Hawaii now and putting him in concentration camps.” Popular syndicated columnist Walter Lippmann wrote that Japan was preparing a raid on the West Coast, and the fact that there had been no evidence of sabotage by Japanese Americans only meant that “the blow is well organized and it is held back until it can be struck with maximum effect.”

Executive Order 9066

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized military commanders to designate zones “from which any or all persons may be excluded, and with respect to which, the right of any person to enter, remain in, or leave shall be subject to whatever restrictions the Secretary of War or the appropriate Military Commander may impose in his discretion.”

Although Japanese Americans were not mentioned in the text of the Executive Order, they were immediately targeted. A new government agency called the “War Relocation Authority” (WRA) was tasked with removing “enemy aliens” from these designated zones. The WRA forcibly deported approximately 120,000 Issei and Nisei to ten relocation camps in seven states:

- Gila River, Arizona

- Granada (Amache), Colorado

- Heart Mountain, Wyoming

- Jerome, Arkansas

- Manzanar, California

- Minidoka, Idaho

- Poston, Arizona

- Rohwer, Arkansas

- Topaz, Utah

- Tule Lake, California

In a March 1942 poll, 93% of Americans supported moving Japanese “aliens” from the Pacific coast. 59% of Americans also approved removing the Nisei to camps, even though they were American citizens.

It is clear that the Issei and Nisei were targeted because of their ancestry. The War Relocation Authority detained only 14,000 “enemy aliens” born in Europe (most from Germany or Italy, both Axis powers and wartime enemies of the United States) out of the more than one million European immigrants living in the United States who were not yet US citizens. The millions of Americans whose parents had immigrated from Europe were not forcibly removed, but the Nisei were.

Deportation and Life in the Camps

Local authorities on the West Coast forced all “persons of Japanese ancestry” to register. The Issei and Nisei were then deported, first to temporary “assembly centers” and from there to relocation centers. They were allowed to bring only a few personal belongings, and many were forced to sell businesses, homes, and farms at great losses to white Americans in the process. Historians estimate that Japanese Americans lost $350 million through these sales (the equivalent of more than $5 billion in 2018).

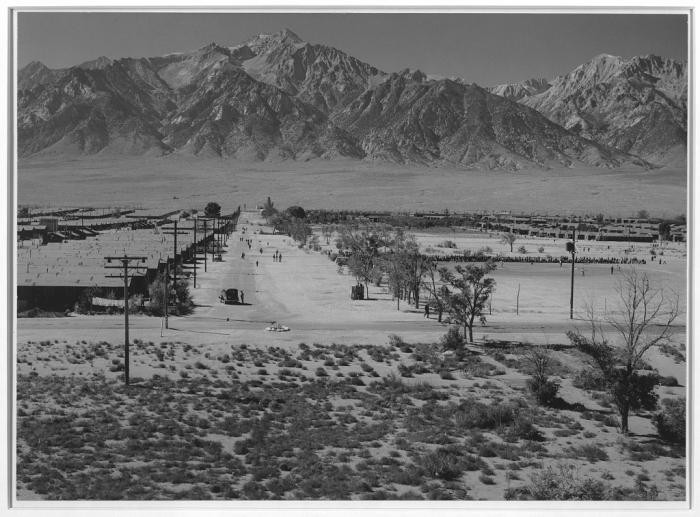

Japanese American Relocation: Photographs At the camps, deportees found rudimentary barracks and other buildings surrounded by barbed-wire, and guarded by the US Army. The Manzanar camp in eastern California, established on the Paiute Native American tribal lands, ultimately had 504 barracks, and families were each allocated 20 x 25 feet of living space. Toilets, laundry, and bathing facilities were communal.

Despite these austere conditions, internees attempted to make their lives feel as normal as possible through gardening, cultural events, and playing sports such as baseball. Interned prisoners attended schools, joined scout troops, or opened small businesses that catered to their fellow prisoners.

Nisei men forcibly relocated to these camps were not permitted to enlist in the US military until 1943. (Men of Japanese ancestry living in Hawaii were allowed to serve immediately after Pearl Harbor.) The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, formed in 1943 and led by white commanders, was made up entirely of Nisei, most of whom still had families in the camps. The 442nd’s soldiers fought in Italy, southern France, and Germany, and became the most decorated military unit for its size and length of service in American history. Members of the 552nd Field Artillery Battalion, part of the 442nd, liberated Kaufering IV Hurlach, a subcamp of the Dachau concentration camp.

Opposition to Relocation

Not all Americans supported the forced removal of Issei and Nisei. Milton Eisenhower, the brother of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, opposed relocation, even though he served as the first director of the War Relocation Authority. (He resigned his position as director after just three months and was replaced by Dillon Myer.) In 1943, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt visited the Gila River camp and gave a speech to the internees in which she called their removal a “mistake” caused by “unreasoning racial feeling.”

Japanese Americans challenged curfew, evacuation, and detention orders in US courts at least 12 times during the war. Four cases reached the US Supreme Court. In each, the court concluded that the war powers of Congress and the president justified forcibly detaining Japanese American citizens in camps. In 1944 the US Supreme Court decided in Korematsu v. United States that removal of Japanese American citizens in this case was in fact constitutional. In 2018, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts condemned that decision, writing, "The forcible relocation of U.S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race is objectively unlawful...Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and—to be clear—'has no place in law under the Constitution.'"

The End of the War

In July 1944, General Charles Bonesteel, the head of the Western Defense Command, wrote to the War Department that “there is no longer a military necessity for the mass exclusion of the Japanese from the West Coast as a whole.” Still, many internees remained incarcerated at the end of the war. After the War Relocation Authority closed camps, US officials gave internees little or no financial or material support, simply forcing them to leave the camps.

Upon their return from imprisonment, Japanese Americans often discovered that their homes, lands, and businesses had been confiscated by the US government or by other Americans. Many sought to regain their prewar property, often unsuccessfully.

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act, formally apologizing on behalf of the US government and granting $20,000 to each surviving detainee. The act explained that “racial prejudice, wartime hysteria and a lack of political leadership” led to the forced removal of people of Japanese ancestry. Some of the relocation camp sites have become National Historic Sites under the US National Park Service.

Critical Thinking Questions

- How and why do some governments justify forced relocation of specific groups?

- Explore other groups that have been moved in American or other national contexts, past and present. Look for patterns, similarities, and differences.