Abstract

Despite the continued use of social media in educational contexts, there remains skepticism about whether platforms like Twitter can actually contribute to learning. In this paper, we argue that such skepticism is based on an overly narrow conception of learning that focuses on academic performance and disregards other manifestations. To advance this argument, we document use of the #bac2018 Twitter hashtag in the month leading up to the 2018 baccalauréat exams (the “bac”), which are significant not only for their role in the French educational system but also for their connections with broader French society and culture. We found that participants engaged in sharing notes; slacking, doubting, and fearing; requesting retweets; preferring topics; complaining; connecting with bac heritage and experience; joking; and showing awareness of time. In keeping with the significance of the bac, we found that these practices within the #bac2018 hashtag were associated with not only academic learning but also social and cultural practices that are significant despite their absence from any formal curriculum. These findings underline the complexity and richness that characterizes learning—especially in digital contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

The continued use of social media for educational purposes (see Greenhow et al., 2019) has been met with continued skepticism about its affordances for learning. For example, Barbetta et al. (2019) published a study in which using Twitter appears to have “reduc[ed] performance on a standardized test score by about 25–40% of a standard deviation” (p. 3). Barbetta and colleagues suggested that these results may indicate that “Web 2.0 platforms decrease students’ performance” (p. 3), which stands in contrast to previous work's general optimism about these platforms (e.g., Greenhow et al., 2009).

While Barbetta and colleagues’ findings make an important contribution, there are other ways to understand what it means to learn. It may well be the case that Twitter is not well suited to support learning as measured by a standardized test in a literature classroom, but with respect to social media and other digital technologies, it can be helpful to expand one’s conception of learning beyond defined curricula and subject matters (Gee, 2003; Greenhow & Robelia, 2009). This broader conception of learning is part of a sociocultural view of learning as engaging with—and thereby acquiring—“[community] practices and participatory abilities” (Greeno et al., 1996, p. 23). Even within a classroom setting, this sociocultural view offers important advantages over a conception of learning that limits its focus to academic performance. For example, Selwyn (2007b) suggests that young people must learn to become students at the same time that they learn the subjects they are studying, despite the fact that researchers tend to concentrate on the latter more than the former. Indeed, the twentieth century saw the emergence of a number of theories conceptualizing a hidden curriculum (see Kentli, 2009) that socializes and enculturates students independently of an official curriculum focused on subject matter knowledge.

In response, we present an exploratory examination of how participants use #bac2018 Twitter hashtag and what implications this presents for learning. On Twitter, hashtags are key words or phrases that index posts on a particular topic—in this case, the 2018 offering of the French Republic’s baccalauréat exams for secondary students. We will use a literacies framework to consider how social media activity might reflect different kinds of learning. Unsurprisingly, the importance of these exams led students to use the Twitter hashtag in efforts to support academic learning. However, the significance of the bac in France—and particularly among French students—drew attention to ways that hashtag activity connected with learning to participate in student or cultural communities. Our findings underscore the potential of social media to support learning. More importantly, they offer important insight into how learning on social media should be understood and framed: as perhaps distinct from common conceptions of (academic) learning and as situated in social and cultural contexts.

Conceptual framework

In this section, we lay out a conceptual framework for learning that equates it with acquiring literacies that are developed through participation in communities. Since at least the 1990s, the field of new literacies has provided a sociocultural framework for understanding learning (Knobel & Lankshear, 2014). Whereas literacy is typically considered in singular, universal terms as command of reading and writing, a (new) literacies framework recognizes multiple “socially recognized ways of generating, communicating and negotiating meaningful content through the medium of encoded texts within contexts of participation” (Lankshear & Knobel, 2006, p. 64). In other words, any meaningful practice or significant body of knowledge within any social context (Gee, 1989) or academic discipline (Gee, 2003) can be thought of as “a literacy.”

Some of these literacies may correspond to defined academic subjects, while others may be specific to the social context from which they emerge. For example, in Curwood’s (2013) examination of literacies present in online spaces dedicated to the Hunger Games franchise, she noted that successful participation in these spaces required adolescents to both “recognize the use of literary techniques” and “understand what the community values in terms of interaction and participation” (p. 421). While the first of these skills may also be valued within an adolescent’s English/Language Arts classroom, the second may be unique to the online space. Nonetheless, as both are meaningful practices valued within a particular social context, both of these qualify as literacies and their acquisition as learning.

Given this understanding of learning, Greenhow and Robelia (2009) have suggested that when considering social media, “adult-driven discourses ought to consider not just ‘academic’ literacies… but also young people’s ‘nonacademic’ communicative literacies” (p. 1131). Similarly, Greenhow and Gleason (2012) have argued for considering “‘tweeting’ as a literacy practice, comprising both traditional and new literacies” (p. 464). While literacies scholars acknowledge that a given literacy may ultimately lack value (e.g., Gee, 2003), they maintain that a more expansive view of learning can be critical for acknowledging authentic learning absent from formal curricula, including learning happening among underprivileged groups (Gee, 1989). Furthermore, much of the learning that humans engage in is divorced from formal contexts—but can be accounted for through a literacies framework. Thus, practitioners and scholars of education cannot fully understand learning (or its broader social implications) by limiting the phenomenon to the demonstrable acquisition of subject matter content.

As previously stated, literacies are acquired by participation in communities. This builds upon Lave and Wenger’s (1991) famous suggestion that “learners inevitably participate in communities of practitioners” (p. 29) and that participation in the activities (i.e., literacies) of the community results in both learning and greater status within the community. Building on this framing, Gee (2003) proposes flipping the traditional question of education researchers on its head: Rather than ask whether something is being learned, he suggests assuming that those participating in a social context are learning something and instead asking what are they learning? Gleason (2013) built on this reasoning by suggesting that literacy acquisition happens through actively participating in Twitter conversations. Thus, to use the #OWS hashtag is to acquire literacies associated with the Occupy Wall Street movement (Gleason, 2013), and should therefore be considered learning. Likewise, tweeting about feminism is practicing feminist literacies and therefore learning to become part of that community (Gleason, 2018). These assertions do not preclude further questions about how and whether these literacies overlap (or don’t) with those valued in formal curricula. Nonetheless, considering social media as a site for learning and social media activity as meaningful invites education stakeholders to consider what they teach us about what education looks like.

Literature review

Education researchers have long been interested in social media as a space for learning and teaching. Indeed, van Osch and Coursaris (2015) noted that between 2004 and 2011, a plurality of the social media research they surveyed was associated with educational topics. Greenhow and Lewin (2016) have argued that social media is “a space for learning with varying attributes of formality and informality” (p. 7, emphasis in original). That is, although social media can be (and has been) used as both an instructional technology within formal institutions of education and a vehicle for informal self- or group-directed learning, it also calls into question the boundaries between these phenomena. We note that a literacies focus is useful across all of these settings. That is, although our conceptual framework is particularly well-suited for documenting and explaining learning in informal settings, Gee (2003) argues that the kinds of disciplinary knowledge (ideally) taught in schools can also be thought of as literacies. Furthermore, Gee (1989) notes that there exist many literacies “connected to schools (different ones for different types of school activities and different parts of the curriculum)” (p. 11). Thus, a literacies framework can help account for meaningful practices that are taught and learned in schools without ever appearing on a syllabus, such as “the informal, cultural learning of ‘being’ a student” (Selwyn, 2007a, p. 18).

Variations in formality are reflected in the literature on students’ use of social media. In Greenhow and Askari’s (2017) review of 24 articles on the use of social network sites in education, they found seven focusing on out-of-school contexts as well as eight addressing classroom contexts and “students’ use of social network sites for: enhanced creativity; new literacies or language learning; engagement in subject matter materials; enhanced student–student and/or student–teacher communication; academic collaboration; and demonstrated thinking skills” (p. 633). Three additional articles were focused on explaining how social media could bridge formal and informal learning. The remaining articles in the review focused on primary and secondary teachers’ use of social media for professional learning. This latter body of work is large enough that it was taken up again in a subsequent review of literature on the use of social media by teachers (Greenhow et al., 2020), which noted that the body of literature addresses their use of social network sites in both formal and informal teacher professional development. This review also looked at research on teachers’ use of social media as part of their classroom teaching, suggesting that social media have been integrated by teachers across academic disciplines (including English, science, mathematics, world languages, social studies, physical education, and religion).

Gao et al.’s (2012) review of the literature on microblogging in education is particularly useful for this study given its focus on Twitter. While they acknowledged that Twitter was used in less-formal learning settings (i.e., at a professional conference) and in a primary school classroom, it is noteworthy that 18 of the 21 articles they reviewed were focused on Twitter’s use in post-secondary settings, including in language, instructional design, new media, and business classes. Gao et al’s. (2012) review also noted that Twitter was used in order to increase participation, extend learning “beyond pre-scheduled class times” (p. 789), expand the scope of the content learned, make learning more interactive, and connect formal and informal learning.

Although researchers have acknowledged the reality of informal learning through social media, much of the literature continues to emphasize implications for formal educational settings. For example, in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers have suggested that social media may be useful for supporting teachers’ transition to emergency remote teaching (Trust et al., 2020) and pedagogical activities during that teaching (Greenhow & Chapman, 2020). Acknowledging the richness of students’ informal learning and asking what the implications are for schools is a long-standing part of research informed by a literacies perspective (e.g., Gee, 2003). For example, Greenhow and colleagues’ (2019) question “What should be the role of social media in education?” draws on learners’ broad use of social media across levels of formality to support intentional designing of social media activities into a broader, formal framework. Similarly, Galvin and Greenhow (2020) have suggested that because students are clearly “writing online prolifically” (p. 57), it is only natural to ask what the implications are for formal classroom settings.

Research context

As previously noted, the context for this study is the #bac2018 Twitter hashtag, which is associated with the 2018 baccalauréat exams for secondary students in France. Before explaining these exams, we first note the significance of the French setting of this research. While research on social media and education documents learning in many countries, the United States continues to receive a disproportionate focus (Greenhow et al., 2020). Fully understanding how social media and learning interact—and understanding how broader social and cultural factors interact with both—requires consideration of this phenomenon across a range of geographical and cultural contexts.

The baccalauréat (or bac) refers both to a diploma recognizing French students’ completion of their secondary studies and to the series of exams required to earn that diploma. There are multiple versions of the bac (general, technical, and vocational), each of which offers different tracks based on combinations of weighted exams on different topics. Earning the bac is typically required for beginning university studies or entering certain professions.

The bac’s importance extends well beyond being an academic qualification. El Atia (2008) describes the bac as culturally significant—an “artifact of France” that dates back to Napoléon Bonaparte (p. 144)—and as socially important—a “symbol to the transition from adolescence to adulthood” (p. 144). The recognized importance of these exams can be seen in the December 2018 “blockading” of over 180 high schools by students upset over proposed reforms to the bac (Bordas, 2018).

Given the importance of the bac in France, it is not surprising that each year’s baccalauréat exams have their own Twitter hashtag, with #bac2018 organizing the conversation around the 2018 bac. For Le Douarin (2014), the pressure of the bac makes their students’ use of digital technology during their final year particularly interesting. Indeed, just as Le Douarin's work found that students use technology to support both their studies and their social relationships, we expected that the #bac2018 Twitter hashtag would serve a range of different purposes.

Present study

In this study, we carried out an exploratory examination of the #bac2018 Twitter hashtag as a site where French secondary students—and other stakeholders—employed literacies (i.e., meaningful practices developed and used in a particular social context). In particular, we asked: How are participants using the #bac2018 hashtag? In keeping with our conceptual framework, we begin with the assumption that because those engaging with #bac2018 are participating in a given social context (in this case, a Twitter hashtag associated with the bac), they are necessarily learning something through engaging with meaningful practices (in this case, tweets) associated with the context. Our purpose, therefore, is to provide a preliminary documentation of what #bac2018 participants are doing, explain what they are therefore learning, and suggest what this implies for education broadly.

Method

In this section, we describe our use of digital research methods to collect data from the #bac2018 hashtag and our use of more traditional methods to analyze those data.

Data collection

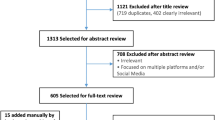

In keeping with growing trends in educational technology research (e.g., Greenhalgh et al., 2021; Gleason, 2013, 2018; Kimmons & Veletsianos, 2018), we focused this study on digital data retrieved directly from social media platforms. We used Twitter Archiving Google Sheets (Hawksey, 2014) to collect tweets containing the #bac2018 hashtag during the month prior to the beginning of the exams on 18 June. This process resulted in the identification of 8523 original tweets, by which we mean the original instance of any tweet (including replies, quote tweets, etc.) as opposed to a repost of someone else’s tweet (i.e., a retweet). In November 2018, we then used the rtweet package for the R programming language (Kearney, 2018) to clean the data and collect useful metadata, including the total number of times each post had been retweeted up to that point. Because human analysis of all original tweets would have been impractical, we then considered sampling strategies.

We elected to limit our focus to the 1% of original tweets (n = 85) that were retweeted the most as of November 2018 (when we collected tweet metadata). Our purpose in our sampling strategy was to most parsimoniously represent the breadth of actual activity in the #bac2018 hashtag. Because of Twitter’s retweet function, our collection of original tweets is only a part of the overall story of that activity; indeed, research on other educational hashtags has shown that retweeting to one's own network is often a more common experience than posting original tweets (Greenhalgh & Koehler, 2017; Staudt Willet, 2019). In our dataset, the average original tweet was reposted by 22.46 users and presumably read by yet more: considerable activity not represented within the original posts themselves. Furthermore, the median original tweet was actually not reposted by additional users, suggesting that only a relatively small number of tweets were reposted (a large number of times). Thus, randomly sampling original tweets would have provided a distorted view of #bac2018 activity, giving tweets that were seen, interacted with, and retweeted thousands of times the same weight as a tweet that—conceivably—no one besides its author saw or interacted with.

In contrast, the top 85 most-retweeted posts represented 160,005 of the 199,953 demonstrable instances of the tweets in our dataset as of November 2018 (i.e., 8523 original tweets and 191,430 retweets of them). Thus, coding the top 1% of original tweets was functionally equivalent to analyzing 80% of activity after accounting for retweets, ensuring broad representation of the phenomenon as actually experienced—and despite a large dataset. In short, if a Twitter user saw only one instance of one tweet containing the #bac2018 hashtag composed during this timeframe, there is a high probability that it was one of the tweets we coded.

Data analysis

To facilitate analysis, the first author translated our data from French to English. The fourth author, a native speaker of French, checked and corrected translations and, when appropriate, provided contextual details.

We then began analysis by collectively reviewing the 85 tweets and—as a group of all four authors—discussing common themes. We used an inductive method of category development, in which categories were created on the basis of the textual (and media) properties of the tweets. This involved creating categories to put similar tweets together (treating each tweet as an indivisible unit) in line with qualitative data analysis (Lindlof & Taylor, 2011). This also follows Gleason’s (2013) example of a thematic analysis of tweets.

Based on that discussion, the first two authors then developed nine mutually exclusive codes that described how participants were using the #bac2018 hashtag. Using that coding scheme, they then individually assigned a single code to each tweet. Lindlof and Taylor (2011) note that the “major purpose of codes is to characterize the individual elements constituting a category” (p. 248). Therefore, we sought to use these codes to locate the patterns in the tweets we had categorized. The codes were mutually exclusive to ensure that we coded for key meanings; to ensure that each tweet only corresponded with one code, we developed a detailed code book that anticipated possible confusion and provided specific guidance.

To check for the reliability of the coding scheme, the first two authors coded all tweets. The coders agreed 75.29% of the time and achieved a Cohen’s kappa score of 0.72, which can be understood as substantial (Landis & Koch, 1977). Nonetheless, the coders resolved all disagreements, combined two codes that proved too similar, and asked the other authors to review and approve their work. The resulting eight codes (along with descriptions and examples) can be seen in Table 1.

Results

In this section, we describe each of the eight ways that we saw participants using the #bac2018 hashtag. In keeping with our conceptual framework, identifying ways that people participate in this social context indicates ways in which learning may be happening—a subject we will address in the Discussion section. Table 1 indicates the number of tweets that were coded as relating to each practice, provides an example for each code, and indicates the number of original tweets (and the corresponding number of total instances) associated with each code.

Sharing notes

The most common code (in terms of original tweets) described tweets in which participants shared resources, advice, or subject matter knowledge related to the bac. Notes usually took the form of a thread—multiple tweets connected together to make an extended point or share several resources. In these tweets, students exhibit peer teaching behaviors by compiling study notes and tweeting links to them. Other tweets gave advice on how to prepare for the bac or what to expect from particular tracks within the bac. By using the hashtag to help each other comprehend the course materials, they extend typical studying behaviors to new, social media spaces. For example, in this tweet—“I see that #Bac2018 and more specifically the #BacPhilo are coming up  As a result, I’m going to share with you the notes that allowed me to have a 18/20 in philosophy even though philosophy was synonymous with naptime for me during my senior year

As a result, I’m going to share with you the notes that allowed me to have a 18/20 in philosophy even though philosophy was synonymous with naptime for me during my senior year  ♂

♂ 1 RT = ONE SAVED HIGH-SCHOOLER

1 RT = ONE SAVED HIGH-SCHOOLER  ”—a former student shared the notes to which he attributed his success on the philosophy exam. Notably, this particular tweet received 23,651 retweets, the highest number of any tweet in our sample. In this code, students learn the content in their own way while interacting with their peers in a familiar social media setting.

”—a former student shared the notes to which he attributed his success on the philosophy exam. Notably, this particular tweet received 23,651 retweets, the highest number of any tweet in our sample. In this code, students learn the content in their own way while interacting with their peers in a familiar social media setting.

Slacking, doubting, and fearing

The second-largest code described tweets that expressed concern about an individual or a group’s failure or lack of preparation for the exams. One such tweet asked, “Am I the only one who’s studying but feels like they aren’t getting anywhere? #Bac2018.” It seemed the student came to Twitter to share their worry about exam preparation. Other tweets were often humorous. For example, some students joked about how little they knew going into the bac or even that they were procrastinating by reading tweets about the bac instead of studying for it. However, they could also be much more serious, with one student expressing seemingly real concern about disappointing their parents.

Requesting retweets

This code described tweets containing variations of the message “retweet or you won’t pass your bac.” The retweets were also used as a way of sharing luck among the students, as in this tweet, “RT for good luck #bac2018. We also used this code to designate tweets that commented on or criticized this meme. As noted in Table 1, this meme was relatively successful, making up more total instances than any other category.

Preferring topics

In these tweets, students identified topics that they would prefer to have or not have on their test. The bac is divided into different subjects depending on a student’s track, and a number of topics may appear for each subject. For example, “I hope it’ll be a color-by-numbers on the math bac #Bac2018” is a humorous riff on this practice, though a more serious request might suggest that the history-geography exam should not include maps.

Complaining

Tweets that expressed frustration with the bac exams or with other students were also present in our data. Some of the complaints were about the structure of the test, including the subjects offered or the way that they were weighted. Other tweets were more general complaints about the demands of the test (e.g., “damn, who invented the History/Geography test, they're a real SOB, when is someone capable of learning more than 20 chapters and 7 maps anyway #Bac2018”). There were several tweets complaining about the history-geography exam, mostly about the difficulty in studying for it. Some tweets were also resentful complaints about high-performing students.

Connecting with bac heritage and experience

This code encompasses tweets that acknowledge or demonstrate the role of the bac in French society. Indeed, it is a testament to the importance of the bac—and its Twitter hashtag—that several high-profile members of French society, including Jean-Michel Blanquer (then-Minister of National Education) and, as seen in Table 1, Jamy Gourmaud (a well-known educational television presenter) used the #bac2018 hashtag. Some of the tweets also mentioned aspects of bac history or commented on the events that defined the bac experience. For example, one student tweeted a 1990 video of students saying they hadn’t studied much, commenting that little had changed since. They noted, “happy to see that in 28 years of Bac nothing has changed for students about studying lmao” Participants also commented on changing calculator policies and on the difficulty of the registration form to be completed before writing the test. All these details showed that these students recognized their participation in the bac as an experience common to students across the country and throughout its history.

Joking

This code was for tweets that were judged as intending to amuse the reader—without fitting into any other code. Participants regularly used humor in their #bac2018 tweets, but tweets coded in this way did not, for example, show doubts or complain about the bac in a humorous way. Rather, they focused uniquely on humor, including memes, videos, or jokes about preparing for and taking the test. For example, one tweet—“Kindergarteners, let me give you some advice: start studying history/geography #bac2018”—was a humorous take on perceptions of insufficient preparation time. Another humorous tweet embedded an ad from a French company that used a joke product—water bottles with baccalauréat cheat sheets printed on the labels—to connect with the bac season and thereby drum up publicity. Although there were relatively few of these tweets, Table 1 shows that they enjoyed collective popularity in terms of total instances.

Showing awareness of time

Although it was the smallest code emerging from our analysis, time was another factor for people tweeting about the 2018 bac exams. These tweets indicated disbelief on how close the test was to the date of the tweet, usually out of excitement or dread. Some tweets also included nostalgia, stemming from students' recognition that their high school years were almost at an end. For example: “Every year you see others take the BAC then comes the time when it's your turn #bac2018.” This awareness of time alludes to their seeing the bac as a rite of passage and the culmination of the high school experience, a necessary part of their education and culture.

Discussion

If participating in Twitter conversations can be considered a kind of learning (Gleason, 2013, 2018), then identifying the conversations students—and others—are participating in will indicate what they are learning. In the following sections, we categorize our findings into broad categories of learning. That is, we summarize what #bac2018 participants are doing and explain what they are therefore learning—which, in conjunction with our literacies framework, may not correspond with the way learning is often conceived of in classrooms. However, throughout these sections, we suggest what this implies for education; in particular, we articulate the benefits for teachers of both (1) acknowledging the existence of several kinds of learning and (2) considering how social media may support each of those kinds of learning.

Academic learning

Given that #bac2018 was a Twitter hashtag focused on formal exams, it should come as no surprise that it served as a space for studying formal academic subjects. That is, the information shared and literacies practiced in the #bac2018 space included those associated with the content areas defined and delimited by the French education system. This mirrors Le Douarin’s (2014) description of bac-takers’ uses of online and digital technologies to supplement their formal lessons. Indeed, the most frequently-appearing activity in terms of original tweets—sharing notes—typically involved students’ taking notes or resources that they had collected in schools and sharing them with other students via the Internet. That this practice is the most common among the most widely shared #bac2018 tweets makes it especially significant. While most internet users are familiar with the concept of online content “going viral” (i.e., being widely shared), one would be forgiven for not expecting a student’s photographed philosophy notes to be shared over 20,000 times.

Participants’ use of #bac2018 for academic learning illustrates the way the way that social media can bridge formal and informal learning contexts (e.g., Greenhow & Lewin, 2016). Therefore, teachers need to be cognizant of the potential social media holds for their students’ learning experience. In the case of the data that we have collected, students have shown that they extend their acquisition of disciplinary literacies from the classroom into social media spaces. Teachers may make the most of this potential by being informed about where students are learning online. They may ask students what social media spaces they find useful for learning about certain topics and then engage with those spaces. This does not mean they have to engage with those spaces in the classroom; rather, if teachers research and review the activity happening within those spaces, they will be able to recommend useful spaces to their students, warn them against unreliable spaces, or otherwise explicitly discuss potential connections between classroom learning and learning through social media.

However, it is also possible to extend students’ learning from social media spaces into the classroom. For example, teachers can engage their students in discussion about what they are learning through social media. This is a great opportunity to start conversations in the classroom space about what information students are consuming and sharing. For example, if a misconception on a topic is trending, the opportunity for a teachable moment presents itself. Whatever approach they take, teachers should be cognizant that social media platforms are not a “this” or “that” mindset. Instead, they can view social media platforms as a complementary tool for information sharing and seeking. In particular, content from social media threads should be shared in the classroom to enhance and supplement—not set—the curriculum.

Social learning

Our findings also demonstrate the presence in #bac2018 of learning that is associated with schooling but distinct from curriculum. As Selwyn (2007a, 2007b) noted, social media spaces can support the “learning of being a student, with online interactions allowing roles to be learnt, values understood and identities shaped” (Selwyn, 2007b, p. 4). For example, although Preferring Topics, Complaining, and Showing Awareness of Time are not likely to be formally taught, they are undoubtedly a key part of the student experience. Furthermore, participation in #bac2018 may be fostering a sense of student connectedness (see Dwyer et al., 2004; Kaufmann et al., 2016) or community that extends beyond the classroom walls to a shared public, mediated space. Students engaging in practices such as Joking and even Slacking, Doubting, and Fearing are connecting (and commiserating) over a typical student experience being shared across the country.

Although teachers are often—and understandably—focused on the academic learning described in the previous section, there are benefits to recognizing the existence of social learning (and its connections to social media). The social learning evident in our data and discussed by Selwyn (2007a, 2007b) is less about becoming an effective student and more about sharing the student experience. However, merely recognizing a concept of learning to be a student—independent of learning academic content—may inspire teachers to dedicate some of their class time to teaching school literacies (study habits, time management, etc.) that are absent from the syllabus but nonetheless key to learning.

Furthermore, teachers may also benefit from encouraging students to find their own social media spaces in which to share their experiences with each other, even if they would not approve of all of all of the complaining and joking happening therein. Indeed, Greenhow and Chapman (2020) suggest in the context of pandemic-driven emergency remote teaching, “it can be difficult for students to feel a sense of camaraderie and community in formal learning management systems which emphasize content delivery and are controlled by their teacher” (p. 344), but that social media may be helpful for recreating on the internet student practices that would usually exist in classrooms, school hallways, and cafeterias. Linvill et al. (2018) have also noted that students have used social media as a space for expressing dissent about instructor ideology; while teachers and students may not wish to adopt this informal practice formally, there may yet be ways to take inspiration from students’ use of social media in this way.

Teachers should also recognize that social learning in the sense of adopting a role in a social context is not limited to the role of students in the context of schools. In Gee’s (2003) discussion of learning as the acquisition of literacies, he suggests that classrooms are too often focused on the acquisition of facts (e.g., the mere memorization of the periodic table) and too rarely focused on the adoption of the identity associated with a discipline (e.g., thinking and acting like a scientist would). Not only would teachers’ recognition of social learning help make this shift in the classroom, but social media may prove to be an important tool for teachers in this vein. For example, Greenhow and colleagues (2019) suggest that “social media can enhance students’ connection to communities” in which they “explore identities” (p. 180). Similarly, Chapman and Marich (2021) discuss how teachers have used Twitter to help students in the social learning of the role of (digital) citizen (see also Greenhow & Chapman, 2020).

Cultural learning

Cultural learning is another activity that is present in schools even if absent from the formal curriculum. As previously described, the bac is more than just a typical student experience—it is closely tied to the French Republic itself. Indeed, tweets that we coded as Connecting with Bac Heritage and Experience involved news stories about the delivery of the exams to local high schools, satirical bac prompts mocking then-French president Emmanuel Macron and his agenda, and well-wishes to students from a prominent television presenter. Prinsloo (2014) notes that human practices often “draw on background know-how, habits, and disposition that often are not based on or explicitly communicated as beliefs or rules” (p. 487)—these tweets show how the #bac2018 hashtag served as a place for acquiring and demonstrating the background knowledge needed to be recognized as a graduate of a French lycée.

In addition to learning to be French, our data suggests that participants were also learning to be on the internet. The Requesting Retweets practice can be understood as a meme, or a “group of digital content units sharing common characteristics of content, form, and/or stance” (Shifman, 2014, p. 176). This particular meme bears similarity to Boyer and Liénard (2006)’s description of cultural rituals “intuitively recognizable by their stereotypy, rigidity, repetition, and apparent lack of rational motivation” (p. 1). Even though students understand that retweeting a post will not affect their performance, there remain compelling cultural reasons to participate in the ritual. Furthermore, some of the tweets in this code (and others) made reference to memes that originated elsewhere on the internet but were repurposed to make sense within the context of the bac, thereby demonstrating familiarity with online culture.

As with the social learning we have previously discussed, a teacher who conceives of their job as primarily focused on the acquisition of academic content might be forgiven for overlooking cultural learning as a phenomenon that happens within the classroom. Yet, an American teacher considering the (presumably) unfamiliar experience of French students taking the baccalauréat would likely have little trouble recognizing particular ways in which that educational experience is embedded in that cultural context. Just as El Atia (2008) describes the bac as an “artifact of France” (p. 144), teachers may benefit from critically considering how what they teach and how they teach it are artifacts of local culture—and, if needed, making necessary adjustments.

Likewise, our findings demonstrate that social media activity is also culturally-situated—that is, full understanding of the posts that we studied required familiarity with French culture. Teachers addressing culture in the classroom—perhaps to explicitly challenge or expand beyond the influence of local cultures—may therefore find social media to be a valuable tool. For example, Eamer et al. (2014) found one social media platform “enabled students to easily share details about their cultural heritage… bringing an acute awareness to the diversity in the class” (p. 66). Alternatively, Chapman and Marich (2021) commented on two teachers’ uses of Twitter to connect their students with people in (respectively) other parts of the country or across the world. Finally, while internet culture may not be the focus of any formal curriculum, teachers who can find ways to relate it to the curriculum may be able to better connect with students.

Future research

While a literacies-focused conceptual framework acknowledges many kinds of learning, it also acknowledges that not all of these kinds of learning are useful or desirable (e.g., Galvin & Greenhow, 2020; Gee, 2003). Although this exploratory study has established #bac2018 as a site where academic, social, and cultural learning appear to be taking place, further research is needed to determine the extent to which participation in this space supports the learning outcomes valued in formal schooling. Most pressingly, educators may wish to know whether participation in informal note-sharing spaces leads to higher achievement on major assessments like the bac or if the test advice shared on social media is of any real value. However, our findings have highlighted a number of practices that educators could profitably investigate with a narrower focus and a longer timeframe—and even suggest other potential avenues of exploration. For example, given students’ expressions of school-related doubt and fear through #bac2018, researchers might consider whether and how emotional learning happens through social media.

Conclusion

Twitter activity surrounding the French baccalauréat in the month leading up to the exams provides a compelling example of what it means to learn through social media. Students used this platform to exchange notes and resources as they continued their studies but also engaged in activities that helped them develop literacies (i.e., meaningful practices) valued in social and cultural contexts. The co-existence of these different kinds of learning underlines the importance of broader views of learning—especially when considering social media. The #bac2018 hashtag serves as a reminder that learning may be academic, social, or cultural—not only on social media, but also in classrooms.

References

Barbetta, G. P., Canino, P., & Cima, S. (2019). Let's tweet again? The impact of social networks on literature achievement in high school students: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial (Working Paper 81). Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Dipartimento di Economia e Finanza (DISCE. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/202855

Bordas, W. (2018). Plus de 180 lycées bloqués dans toute la France [More than 180 high schools blockaded in all of France]. Le Figaro Étudiant.

Boyer, P., & Liénard, P. (2006). Why ritualized behavior? Precaution systems and action parsing in developmental, pathological and cultural rituals. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29, 1–56.

Chapman, A. L., & Marich, H. (2021). Using Twitter for civic education in K-12 classrooms. TechTrends, 65, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-020-00542-z

Curwood, J. S. (2013). The Hunger Games: Literature, literacy, and online affinity spaces. Language Arts, 90(6), 417–427.

Dwyer, K. K., Bingham, S. G., Carlson, R. E., Prisbell, M., Cruz, A. M., & Fus, D. A. (2004). Communication and connectedness in the classroom: Development of the connected classroom climate inventory. Communication Research Reports, 21(3), 264–272.

Eamer, A., Hughes, J., & Morrison, L. J. (2014). Crossing cultural borders through Ning. Multicultural Education Review, 6, 49–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/2005615X.2014.11102907

El Atia, S. (2008). From Napoleon to Sarkozy: Two hundred years of the baccalauréat exam. Language Assessment Quarterly, 5, 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434300801934728

Galvin, S., & Greenhow, C. (2020). Writing on social media: A review of research in the high school classroom. TechTrends, 64, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-019-00428-9

Gao, F., Luo, T., & Zhang, T. (2012). Tweeting for learning: A critical analysis of research on microblogging in education published in 2008–2011. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 783–801. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01357.x

Gee, J. P. (1989). Literacy, discourse, and linguistics: Introduction. Journal of Education, 171, 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205748917100101

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy (revised and updated edition). St. Martin’s Press.

Gleason, B. (2013). #Occupy wall street: Exploring informal learning about a social movement on Twitter. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 966–982. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479372

Gleason, B. (2018). Adolescents becoming feminist on Twitter: New literacies practices, commitments, and identity work. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62, 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.889

Greenhalgh, S. P., & Koehler, M. J. (2017). 28 days later: Twitter hashtags as “just in time” teacher professional development. TechTrends, 61, 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0142-4

Greenhalgh, S. P., Koehler, M. J., Rosenberg, J. M., & Staudt Willet, K. B. (2021). Considerations for using social media data in learning design and technology research. In E. J. Romero-Hall (Ed.), Research methods in learning design and technology (pp. 64–77). New York, NY: Routledge.

Greenhow, C., & Askari, E. (2017). Learning and teaching with social network sites: A decade of research in K-12 related education. Education and Information Technologies, 22, 623–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-015-9446-9

Greenhow, C., & Chapman, A. (2020). Social distancing meet social media: Digital tools for connecting students, teachers, and citizens in an emergency. Information and Learning Sciences, 121(5/6), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0134

Greenhow, C., Galvin, S. M., Brandon, D. L., & Askari, E. (2020). A decade of research on K-12 teaching and teacher learning with social media: Insights on the state of the field. Teachers College Record, 122(6), 1–72.

Greenhow, C., Galvin, S. M., & Staudt Willet, K. B. (2019). What should be the role of social media in education? Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 6, 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732219865290

Greenhow, C., & Gleason, B. (2012). Twitteracy: Tweeting as a new literacy practice. The Educational Forum, 76, 463–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2012.709032

Greenhow, C., & Lewin, C. (2016). Social media and education: Reconceptualizing the boundaries of formal and informal learning. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(1), 6–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1064954

Greenhow, C., & Robelia, B. (2009). Old communication, new literacies: Social network sites as social learning resources. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14, 1130–1161.

Greenhow, C., Robelia, B., & Hughes, J. E. (2009). Web 2.0 and classroom research: What path should we take now? Educational Researcher, 38, 246–259. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09336671

Greeno, J., Collins, A., & Resnick, L. (1996). Cognition and learning. In D. Berliner & R. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 15–46). Macmillan.

Hawksey, M. (2014). Need a better Twitter archiving google sheet? TAGS v6.0 is here! [Blog post]. https://mashe.hawksey.info/2014/10/need-a-better-twitter-archiving-google-sheet-tags-v6-0-is-here/

Kaufmann, R., Sellnow, D. D., & Frisby, B. N. (2016). The development and validation of the online learning climate scale (OLCS). Communication Education, 65(3), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2015.1101778

Kearney, M. W. (2018). rtweet: Collecting Twitter data. (Version 0.6.7) [Statistical software]. https://cran.r-project.org/package=rtweet

Kentli, F. D. (2009). Comparison of hidden curriculum theories. European Journal of Educational Studies, 1(2), 83–88.

Kimmons, R., & Veletsianos, R. (2018). Public internet data mining methods in instructional design, educational technology, and online learning research. TechTrends, 62, 492–500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0307-4

Knobel, M., & Lankshear, C. (2014). Studying new literacies. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 58, 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.314

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159–174.

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2006). New literacies: Everyday practices & classroom learning. Open University Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Le Douarin, L. (2014). Une sociologie des usages des TIC à l’épreuve du temps libre : Le cas des lycéens durant l’année du baccalauréat. [A sociological study of ICT use during free time: The case of students during the baccalauréat year]. Recherches En Education, 18, 11–26.

Lindlof, T. R., & Taylor, B. C. (2011). qualitative communication research methods (2nd ed.). . Sage.

Linvill, D. L., Boatwright, B. C., & Grant, W. J. (2018). “Back-stage” dissent: Student Twitter use addressing instructor ideology. Communication Education, 67(2), 125–143.

Prinsloo, M. (2014). Literacy and the new literacy studies. In D. C. Phillips (Ed.), Encyclopedia of educational theory and philosophy (pp. 487–490). Sage Publications Inc.

Selwyn, N. (2007). ‘Screw Blackboard… do it on Facebook!’: An inestigation of students’ educational use of Facebook. Paper at the Poke 1.0 Facebook Social Research Symposium, London, England.

Selwyn, N. (2007). Web 2.0 applications as alternative environments for informal learning—a critical review. OECD CERIKERIS International expert meeting on ICT and educational performance. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in digital culture. MIT Press.

Staudt Willet, K. B. (2019). Revisiting how and why educators use Twitter: Tweet types and purposes in #Edchat. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 51(3), 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2019.1611507

Trust, T., Carpenter, J. P., Krutka, D. G., & Kimmons, R. (2020). #RemoteTeaching & #RemoteLearning: Educator tweeting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 151–159.

Van Osch, W., & Coursaris, C. (2015). A meta-analysis of theories and topics in social media research. In T. X. Bui & R. H. Sprague (Eds.), Proceedings of the 48th Annual Hawaii International Conference on system sciences (pp. 1668–1675). University Press.

Acknowledgements

Merci à Max pour nous avoir expliqué tout l’argot que nous étions trop vieux pour comprendre nous-mêmes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This research is based on public data and is therefore not considered by the institutional review boards of the University of Kentucky or Michigan State University as falling under their purview. However, as described below, we have applied established considerations for ethical internet research.

Informed consent

As above, because this research is based on public data, it is not considered by the institutional review boards of the University of Kentucky or Michigan State University as requiring informed consent. Nonetheless, we have applied considerations for ethical internet research identified by bodies such as the Association of Internet Researchers and leading researchers in the field. In particular, prior to analysis, we removed all data coming from private accounts or that was deleted by its author (or Twitter) after its original composition. Furthermore, except in the case of public figures, we have made considerable effort to obscure the identities of all those who produced the data considered in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Greenhalgh, S.P., Nnagboro, C., Kaufmann, R. et al. Academic, social, and cultural learning in the French #bac2018 Twitter hashtag. Education Tech Research Dev 69, 1835–1851 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10015-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-021-10015-6